Coffret

1300-1400 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

A casket is a small box for valuables, itself often richly ornamented. Caskets were of great importance for the storage of household goods, but were also valued by medieval travellers who frequently carried with them a major portion of their possessions. For this purpose, containers of a wide variety of shapes and sizes existed. Iron caskets provided a great measure of security but, because of their weight, were not easily portable. Therefore caskets of wood, covered with leather or other material and bound with iron, were more common.

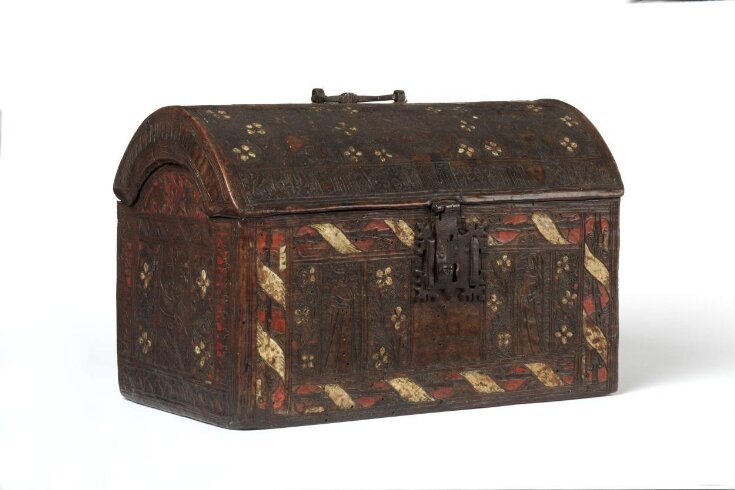

During the Medieval period, love-gifts to a future bride or between a couple were sometimes presented in caskets, and the love inscriptions and scenes of courtship worked in the leather on this casket suggest that it was used in this way. The figures of a lady and a gentleman are shown among flowers and borders of ribbons twisted around branches. On the lid are two figures of knights mounted on griffins, and two naked figures armed with clubs and shields. The meaning may be that the donor/suitor intends, like the honourable knights, to vanquish bestial desire. Chretien de Troyes (writing in the late 12th century) has Yvain, the hero tell his beloved ‘Lady, you carry the key/ and have the casket in which my happiness / is locked’, making explicit the idea that a casket could itself carry symbolic meaning, as well as serving as a practical container for a special occasion.

During the Medieval period, love-gifts to a future bride or between a couple were sometimes presented in caskets, and the love inscriptions and scenes of courtship worked in the leather on this casket suggest that it was used in this way. The figures of a lady and a gentleman are shown among flowers and borders of ribbons twisted around branches. On the lid are two figures of knights mounted on griffins, and two naked figures armed with clubs and shields. The meaning may be that the donor/suitor intends, like the honourable knights, to vanquish bestial desire. Chretien de Troyes (writing in the late 12th century) has Yvain, the hero tell his beloved ‘Lady, you carry the key/ and have the casket in which my happiness / is locked’, making explicit the idea that a casket could itself carry symbolic meaning, as well as serving as a practical container for a special occasion.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Oak, covered with painted leather with iron fittings, moulding |

| Brief description | Coffret with key. Wood, rectangular, with arched lid, covered with leather incised, coloured and gilt |

| Physical description | Casket with key. Wood, rectangular, with arched lid, covered with leather incised, coloured and gilt. On the front are seen standing figures of a lady and a gentleman in panels enclosed by flowers and borders of ribbons twisted around branches. On the sides are flowers, ribbons and various ornamental borders. On the lid are two figures of baladins [paladin, knight errant, one of the Twelve peers of Charlamagne's court, of the Court Palatine was the chief] mounted on griffins, two naked men with clubs and shields, two images of the sun, together with flowers and ribbons, and the legend in Gothic letters, "du bon du [representation of a heart]". At the back are the words " mon [representation of a heart] aves". The meaning is that the knight proceeds "du bon du coeur" to deliver the lady who is the captive of wild men or sorcerers, and who calls to him "mon coeur (vous) avez" or " mon coeur ayez". Iron handles, lock and key. Observations on construction The oak carcase (planed planks) is nailed together, with the base sitting between the front and back boards, and running underneath the end boards. Pieces of thin leather cut to size appear to have been glued (starting 1-2cm over the inner face of each board at the top) over the exterior and then underneath, without any attempt to cover the underside neatly; thicker leather pieces on which the design is worked have been glued over the top and around the corners, but not over awkward joints. Internally, the residue of a textile lining (and weave pattern) is visible after the textile itself has been removed. The curved lid is carved from a solid plank, the underside ends built up with thicknesses of leather, possibly with internal wood stiffeners. The lid is held on two wrought iron hinges fitting into a crude mortice and each element nailed with a single clinched nail; the lock hasp is fitted in the same way. The handle (offset from the centre) is held on two nails. The lock seems old but may be a replacement for a larger one (though there are no old fixing holes visible??). The cutting of the leather for the figures is highly accomplished, while the ornamental details are irregular (and were presumably cut at speed). Some cuts run right down to the wood. Pigments (red, white, green and gold) seems to have been painted on (in some cases directly onto the wood?), and the original scheme would have been very bold. There is a lot now missing. Shellac covering probably dates to 1960s. EDXRF analysis (October 2006) by Dr Lucia Burgio: Red, white and green paint traces on various areas of the coffret were analysed non-destructively by EDXRF. The elements found (mercury, lead and copper) are in agreement with the use of traditional pigments such as vermilion, lead white and a copper-based green. No metals suggesting the presence of modern pigments (such as cadmium, chromium, titanium and zinc) were detected. Costume Man's long hanging sleeves and cap |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions |

|

| Object history | Received from Rollin & Feuardent (61 Great Russell St, London) from the sale of the Odiot Collection at Paris in April 1889. Three objects were purchased (229 to 231-1889.) The minute for approval to bid at the sale - RP/1889/2727 - has not survived but there is a general paper for the purchases at the sale - RP/1889/3718 - & this is on the Rollin & fueardent Nominal file (MA/1/R1475). Adiot collection (lot 107) £50-18-6 A small coffer for jewels or other valuables was known as a casket or coffret (from the French, a small coffre or chest). Such small boxes made of wood covered with leather were often decorated with elaborate decorated and embossed scenes. A notable example of this is the Talbot casket in the British Museum (1977, 5-2,1), made in northern France or Flanders. Various comparable caskets with rounded lids, and decorated and painted leather have been published, usually attributed German, c.1500, see for example Günter Gall, Leder im Europäischen Kunsthandwerk, Braunschweig 1965, nos. 93 (Metropolitan Museum), and 95. p.127-8 Gall suggests that "on the lids there are usually Birth-scenes, while the front and the back of the lid show the annunciation and the annunciation to the shepherds. In addition to this, there often is the very similar lock with the snake as a clasp, which is also repeated on the handle of the lid. Even more relevant is the common understanding of the relief with the slight rise on the plane without a sharp delineation through a cut-line. Considering the number of pieces of this kind, they were perhaps commodities, as the coats of arms are mostly not filled in. After the sale, the buyer could have then had his own crest painted onto it. Works of this type are kept in the Metropolitan Museum in NY, Hamburger Museum fuer Kunst und Gewerbe, the Germanische Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, the Museum for Leathercraft in London and obviously in the Deutsche Ledermuseum in Offenbach (fig. 93, 94, 95). With the pieces in Nuremberg and Offenbach a common workshop can be assumed, the others only reveal a general relationship dictated by time and nationality. These works must have all originated in Germany around 1500. They differ from the French works with the clear line, the less exact arrangement and the softer rise of the relief." |

| Historical context | Casket DEF: A small box or chest for jewels, letter, or other things of value, itself often of precious material and richly ornamented. 1467, Eng. Gilds (1870), p. 379: “The same quayer to be put in a box called a casket.” 1471, J. Paston, Lett. 670iii. 7: “Syche othyr wryghtynges and stuffs as was in my kasket.” Cotgrave: “Boiste (or Boite): a box… little casket.” Cf. also Shakespeare, where many references occur – e.g., The caskets of gold, silver, and “dull lead,” which Portia, in The Merchant of Venice (1594), offers as a test of character to her suitors. The Secular Spirit (Exhibition catalogue, New York, Metropolitan Museum 1975) p.23 Throughout the Middle Ages, household goods of all types were stored in boxes and coffrets which both protected the goods in the home and provided travelling cases on journeys. The great number of these of all sizes, shapes and materials that have survived from the period testify to this method of storage. p.149 Coffrets and caskets, which were of great importance for the storage of household goods, were also valued by medieval travellers, who frequently carried with them a major portion of their possessions. For this purpose, containers of a wide variety of shapes and sizes existed, all intended to secure of the objects enclosed. Iron caskets provided a great measure of security but, because of their weight, were not easily portable. Therefore caskets and coffrets of wood, covered with leather or other material and bound with iron, were more common. p.24 This casket, like many late medieval secular objects, is decorated with scenes of courtship or romances based on medieval concepts of courtly love... The earliest cogent expression of courtly love is probably to be found in the twelfth-century troubadour songs of southern France. The code of courtly love, formalized in the late 12th and early 13th century, was observed, in some places, well into the 15th century. A popular author, Christine de Pisan (c. 1360-1430), expressed the sentiments of the day: “For it is well known there is no joy on earth that is so great as that of the lover and the beloved.” John Cherry, Medieval Decorative Art (London, 1991) pp55- romance and courtly love … first expressed in troubadour poetry, appeared at the end of the 11th century in Languedoc in the S of France. A highly formalised mode of behaviour, it combines the concepts of humility, courtesy and devotion to the ideal of love….the service of a lover to his lady was modelled on that of a feudal vassal to his lord (seen in the representation of the lover kneeling before his beloved and placing hands together) 66 wooden caskets covered with leather were popular in the late 14th and 15th centuries: for whatever reason, perhaps because ivory became scarce, the Parisian ivory caskets enjoyed only a brief and limited period of popularity during the 14th c. Sometimes leather caskets have lovers depicted on them eg the late 14th c Talbot casket (BM) with scenes of lovers in raised leather. Heart as symbol of love. Heart-shaped brooches were exchanged between lovers. 15th century French poet Charles of Orleans advises the courtier how he could combine the gift of a replica of his heart with the trad gift of the lover, the expensive present: Some thing devise, and take [it] for thyn ese, And send it to her, that may her herte apese: Some hert, or ring, or letter, or device, Or precious stone: but spare not for no price 69 The flowering heart demonstrates the growth of love from the heart – commonly expressed on a seal where two hands support a heart amidst floral scrolls with a legend. Widespread use of inscriptions on rings, including heart motif, which repeat each other to the point of banality: mon cuer avez, mon [heart] avez etc. Michael Camille, The Medieval Art of Love – objects and subjects of desire (London 1998) The casket and the key p65ff ‘The box with its metaphorics of opening and closing, interiority and outer surface, was always closely linked to the inviolable female body, open only to her husband-owner. This is true of chests of all sizes and types, from the small ivory caskets made in 14c Paris, through the slightly larger leather and wood Kistlin of 14c Germany to the trunk-size pairs of cassone chests used in the marriage ceremonies of Renaissace Florence. These items were usually bought by the groom and his family to transport gifts to his future bride or part of her dowry to him and then would serve as storage chests, furniture, or jewelry boxes in the couple’s bedroom. Their imagery of control and containment makes them less private and secret objects than open social signs of exchange and goods within a gift economy. As on the more intimate girdles, hybrids and monsters serve here as exemplars of the baser passions of the lower body; tamed, they now serve as protectors…One should not forget the almost sacred status of property in medieval culture. Thefts and crimes against property were punished far more severly than crimes against the body, and much medieval art is not only to be seen as property in itself but as serving to protect it.’ Chretien de Troyes (writing late 12th century) has Yvain, the hero tell his beloved ‘Lady, you carry the key/ and have the casket in which my happiness/ is locked.’ In accepting the box (with his heart) she accept the box’s imaginary universe of relationships and rituals p68. As well as gifts, caskets were also used to relay messages of love in the form of letters… p68-9. Camille stresses that caskets were ‘Not stationary objects in museums, but ‘moveables.’ Boxes were themselves shifted and used to transmit messages, both in themselves and on themselves. The Wildman (seen as both bestial and primitive in a positive sense) is sometimes used to show how the lady tames and controls her suitor’s animal passions. Notes on the manufacture of medieval leather containers: Waterer (and following him, Cherry) summarise the medieval techniques for making leather containers for dry-goods: Stitching is the most common technique, with holes made in leather by awls. Thread is made from flax or hemp yarn rolled with beeswax. The other principal assembly technique is sticking to a wooden structure. The traditional adhesive for box covering is hot animal glue, which was often created as a by-product of the fleshings taken by the tanner from the skins or hides. Leather objects can also be created by moulding. The traditional medieval term was cuir bouilli, though Waterer suggests that boiling could not have been used. The technique is quite simple, and consists of soaking the (vegetable-tanned) leather in cold water until it is thoroughly saturated. The leather is then very plastic and can be modelled over formers in moulds of plaster, wood or metal. If the surface is to be ornamented by tooling, stamping or punching, this must be done while the leather is damp.The leather is then dried gradually (to avoid brittleness), supported by its mould or filling which can be removed later. The most common processes of decorating smooth-surfaced leather are: Incising with blunt or sharp tools Punching to give a texture to the background of incised designs, using a variety of small iron or bronze punches (also used in book binding). Modelling, to leave important features in low relief Embossing, performed with a ball tool from the flesh side of leather that has been previously dampened. Carving, which is done from the grain side with a special knife that can be inserted more orless horizontally and partially raises up a thin layer until the form appears to lie on the surface Finally the object is decorated with coloured dyes, usually with some paint (tempera). Red seems a common colour (little work on medieval dyes). Some leather was gilded using glaire (white of an egg) or gold size to attach gold leaf which adhered under the heat and pressure of book-binding tools. However, Davies argues that the multiple techniques of cuir bouilli have never actually been very clearly established. Cuir bouilli differs from other supported leathers in that after treatment it is rigid (without a support) and water resistant, indicating that the structure of the leather has been altered through a chemical reaction. Otherwise leather would remain flexible unless coated with a stiffening medium or mounted on a backing material. She suggests that all true cuir bouilli was made by taking vegetable-tanned leather and saturating it with water, then heating it to a temperature just before it starts to shrink, removing it from the hot water and moulding it immediately, and if necessary stitching it while wet. In this way the molecular bonding of the leather is weakened but not fully released allowing limited realignment of its molecular structure to take place in a more controlled manner. Alternatively, if the heat source application is limited to only the surface of the wet leather then it is possible that the shrinkage solely occurs in the outer layer of the leather, producing a surface hardening effect and reinforcing the structure. She speculates that by impregnating oils, resins and waxes, it may be possible to mould the structure of the leather when hot, and to produce more detailed surface decoration because otherwise this decoration would be distorted by shrinkage after tooling. Bibliography English medieval Industries (ed John Blair and Nigel Ramsay, London) ‘Leather’ chapter 12 by John Cherry, pp. 295-318 Conservation of Leather and related materials (ed. Marion Kite and Roy Thomson, 2006), ‘Cuir Bouilli’ chapter 10 by Laura Davies, pp. 94-102 Oxford Companion to the Decorative Arts, ed. Harold Osborne (Oxford, rev.ed. 1985) ‘Leathercraft’ entry by John W. Waterer |

| Summary | A casket is a small box for valuables, itself often richly ornamented. Caskets were of great importance for the storage of household goods, but were also valued by medieval travellers who frequently carried with them a major portion of their possessions. For this purpose, containers of a wide variety of shapes and sizes existed. Iron caskets provided a great measure of security but, because of their weight, were not easily portable. Therefore caskets of wood, covered with leather or other material and bound with iron, were more common. During the Medieval period, love-gifts to a future bride or between a couple were sometimes presented in caskets, and the love inscriptions and scenes of courtship worked in the leather on this casket suggest that it was used in this way. The figures of a lady and a gentleman are shown among flowers and borders of ribbons twisted around branches. On the lid are two figures of knights mounted on griffins, and two naked figures armed with clubs and shields. The meaning may be that the donor/suitor intends, like the honourable knights, to vanquish bestial desire. Chretien de Troyes (writing in the late 12th century) has Yvain, the hero tell his beloved ‘Lady, you carry the key/ and have the casket in which my happiness / is locked’, making explicit the idea that a casket could itself carry symbolic meaning, as well as serving as a practical container for a special occasion. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 230-1889 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | July 10, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest