Cup

1858 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

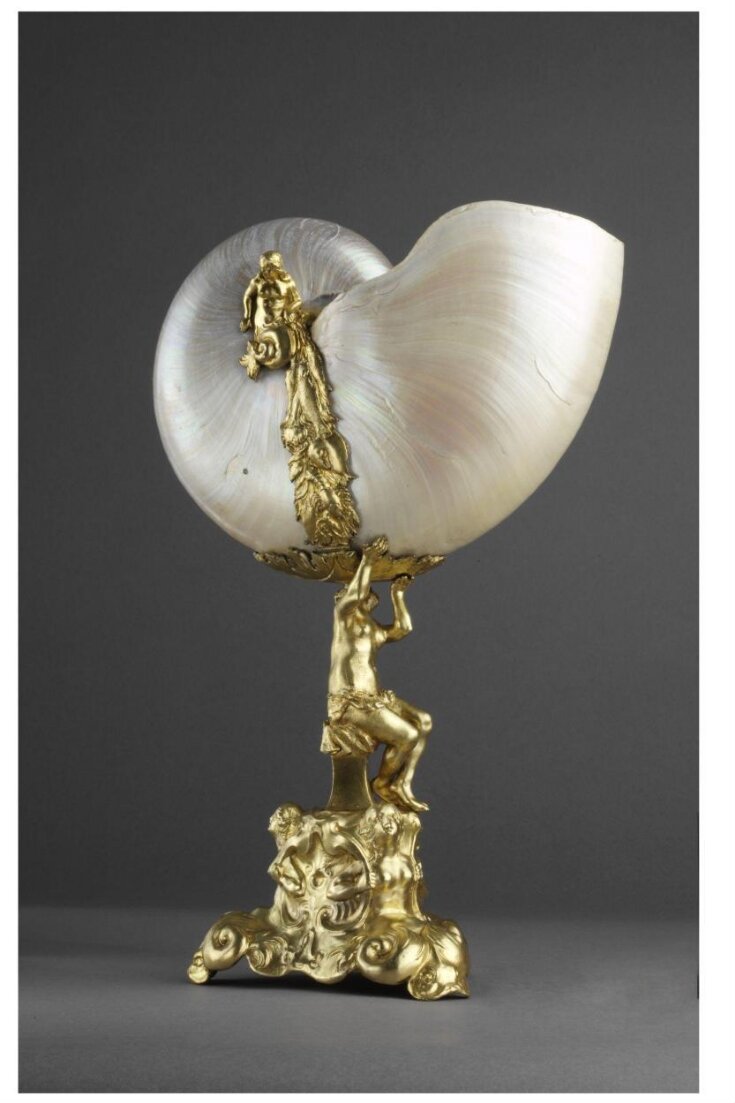

This shell cup is an electrotype, an exact copy in metal of another object. The Museum bought it in 1858 from Messrs Franchi and Son of Clerkenwell for £5.0.

Electrotypes were made using technology patented by Elkington and Company in Birmingham in1840. Metal could be transferred from one object to another when immersed in a vat of potassium cyanide and electrically charged. This cup was electroformed in copper in moulds taken from its original and then electrogilded.

Electrotypes are relics of 19th-century industrialisation. The process of electroplating and electrotyping favoured companies that could afford large factories and expensive technology. The power of the machinery at the disposal of the silver industry allowed modern mass production to develop. Hundreds of electrotypes could be created at once in the vats.

The original silver-mounted nautilus cup was made in around 1630, and is similar to the work of the Van Vianen family of Utrecht, The Netherlands. Shells, stones, coconuts and glass, all elaborately mounted in silver and gold, filled the treasuries of wealthy European princes. The Museum bought electrotype reproductions of these objects so students could study ‘historic’ objects that were otherwise inaccessible.

Electrotypes were made using technology patented by Elkington and Company in Birmingham in1840. Metal could be transferred from one object to another when immersed in a vat of potassium cyanide and electrically charged. This cup was electroformed in copper in moulds taken from its original and then electrogilded.

Electrotypes are relics of 19th-century industrialisation. The process of electroplating and electrotyping favoured companies that could afford large factories and expensive technology. The power of the machinery at the disposal of the silver industry allowed modern mass production to develop. Hundreds of electrotypes could be created at once in the vats.

The original silver-mounted nautilus cup was made in around 1630, and is similar to the work of the Van Vianen family of Utrecht, The Netherlands. Shells, stones, coconuts and glass, all elaborately mounted in silver and gold, filled the treasuries of wealthy European princes. The Museum bought electrotype reproductions of these objects so students could study ‘historic’ objects that were otherwise inaccessible.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Electrotype, copper-gilt |

| Brief description | Cup, made by Franchi and Son, Clerkenwell (London), 1858. |

| Physical description | Electrotype cup formed of a nautilus shell mounted on a base, the stem formed as a 'naiad' (a representation of a water nymph in art and sculpture) supporting the shell above its head and sitting on a three-sided plinth with sirens at her feet. The electrotype is of gilded copper made using the electrotyping process (patented in 1840 by Elkington and Company of Birmingham). The original was of silver, with a cast stem and raised base formed in the very fluid auricular (ear-like) style of the silver designed and made by Van Vianen family of Utrecht in the 1630s. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Production type | Copy |

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | This cup was bought by the Museum in 1858 from Franchi and Son of 15 Myddleton Street, Clerkenwell for £5.0. It is an electrotype copy of a 17th-century nautilus cup, the original probably the work of the Van Vianen family of Utrecht. The cup was a design tool for students in the government schools of design under the aegis of the Department of Science and Art. Historical significance: As an electrotype this cup is an example of a 19th-century design model. Electrotypes play a key role in helping us to understand the V&A in its earliest days. The V&A grew largely out of the Great Exhibition in 1851 and, under the guidance of Henry Cole, sought to arrest the perceived decline in British design. The Museum aimed, initially, to collect ‘modern manufactures’ for the education of manufacturers, designers and the public. Cole was also in charge of the Government Schools of Design, which he set about reforming. Cole passionately believed in the potential of both museums and the schools of design, to raise standards of taste. The appointment of John Charles Robinson as curator of the Museum in 1853 heralded a change in focus. Robinson persuaded Cole that historic works of art were as instructive as contemporary work. For Cole and Robinson, if historic works of art could not be acquired, copies were the next option. The Museum bought electrotypes as part of its growing collection of reproductions. This collection enabled students to look closely at ‘historic’ objects that were otherwise inaccessible. Electrotypes provided the same function as the Museum’s collection of plaster casts. Electrotypes are also relics of 19th-century industrialisation and mass production. The process of electroplating and electrotyping favoured companies that could afford large factories and expensive technology. The power of the machinery and new technology now at the disposal of the silver industry allowed modern mass production to develop. Electroplaters could create thousands of identical objects using a fraction of the amount of silver to create “a degree of mechanical finish it would be difficult to surpass” (Art Union, 1846). The focus of silver and silver product manufacture moved from London to the new factories of Birmingham and Sheffield. Some smaller companies trying to keep pace with industrial change suffered. The large vats of potassium cyanide required spacious, well-ventilated factories. A report at the Great Exhibition claimed workers in smaller companies suffered blistered skin, headaches temporary blindness and nausea. |

| Historical context | This cup is an electrotype, an exact copy in metal of another object. Electrotypes were a by-product of the invention of electroplating (silver plating by electrolysis). ELECTROPLATING: Electricity revolutionised the trade of coating base metal objects with silver. Patented by Elkington and Company in the 1840s, this technique was the fulfilment of a century of research into the effects of electricity on metals. A negatively charged silver bar, suspended in a vat of potassium cyanide, deposited a coating of silver on a positively charged base metal (mostly copper, later nickel-silver) object immersed with it. Electroplated objects were fully formed in base metal before plating. ELECTROGILDING exploited the same technique but used gold bars instead of silver. It was safer than traditional mercury gilding. ELECTROFORMING transferred the metal deposits directly into the moulds in the plating vats. When enough metal had been deposited to create a self-supporting object the mould was removed. Developed by Alexander Parkes, electroforms so accurately mirrored the moulds in which they were created that multiple copies could be created (ELECTROTYPES). This cup was electroformed in copper from moulds of its original and then electrogilded. Early experiments in electroplating, often by amateur scientists using Elkington’s home electroplating kits, involved coating fruit, flowers and animals in silver or gold “with the most perfect accuracy”. They “retained all the characteristics of the specimens before their immersion” (Penny Magazine, 1844). The Art Journal enthused in same year, “The electrotypes are perfect; the finest lines, the most minute dots are as faithfully copied as the boldest objections” Henry Cole, the first director of the South Kensington Museum (V&A), quickly grasped the educational potential of this new technique. He employed Elkington’s and Franchi & Son of Clerkenwell to take moulds of historic objects in the Museum (at their own risk), create copies in a base metal and then electroplate them. These could be sold freely as reproductions, with a gold, silver or bronze finish, provided they bore the South Kensington Museum’s official stamp. To avoid breaking English hallmarking laws, all marks were to be deleted from copies of silver objects. Elkington’s display of electrotypes at the 1867 Paris Exhibition proved extremely popular and prompted Cole to organise a convention at which 14 European countries agreed to exchange works of art. Representatives of Elkington’s and the V&A sent staff to Germany, Sweden, France, Denmark and Hungary. The most ambitious trip, to Moscow and St. Petersburg in 1880, secured copies of over 200 items from the Kremlin and the Hermitage, including the celebrated Jerningham Wine Cooler and much Elizabethan and Stuart silver sent as ambassadorial gifts to the Tsars. By 1920 the V&A held over 2000 electrotypes. Copies toured the country as part of the museum’s educational programmes and were sold to the public and to museums and art schools. |

| Production | Made at the site of the workshop of Messrs Franchi & Son, electrotypists, at 15 Myddleton Street, Clerkenwell, London. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | This shell cup is an electrotype, an exact copy in metal of another object. The Museum bought it in 1858 from Messrs Franchi and Son of Clerkenwell for £5.0. Electrotypes were made using technology patented by Elkington and Company in Birmingham in1840. Metal could be transferred from one object to another when immersed in a vat of potassium cyanide and electrically charged. This cup was electroformed in copper in moulds taken from its original and then electrogilded. Electrotypes are relics of 19th-century industrialisation. The process of electroplating and electrotyping favoured companies that could afford large factories and expensive technology. The power of the machinery at the disposal of the silver industry allowed modern mass production to develop. Hundreds of electrotypes could be created at once in the vats. The original silver-mounted nautilus cup was made in around 1630, and is similar to the work of the Van Vianen family of Utrecht, The Netherlands. Shells, stones, coconuts and glass, all elaborately mounted in silver and gold, filled the treasuries of wealthy European princes. The Museum bought electrotype reproductions of these objects so students could study ‘historic’ objects that were otherwise inaccessible. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | REPRO.1858A-1 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 12, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest