Lectern

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

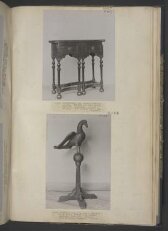

This lectern came from Chirk Castle, Denbighshire, Wales, where it stood in the private chapel until the late nineteenth century, when the chapel was refurbished. The eagle's legs and the stand are later than the eagle, probably added in the early seventeenth century when Sir Thomas Myddelton, the new owner of Chirk Castle redecorated the chapel.

It was customary in medieval churches to place a desk or lectern in the chancel or choir, from which the gospel was read. These were usually of wood or metal, and moveable. After the Reformation it was more common to bring them out into the nave or body of the church, and to use them for reading the lessons. From the about 1300 until after 1500 relatively wealthy churches might use a lectern in the form of an eagle (the symbol of St John the Evangelist), with outspread wings, standing on a globe. Such lecterns could be in cast brass or in carved wood, which was cheaper. Fewer than 20 wooden lecterns of this date survive in England and Wales.

It was customary in medieval churches to place a desk or lectern in the chancel or choir, from which the gospel was read. These were usually of wood or metal, and moveable. After the Reformation it was more common to bring them out into the nave or body of the church, and to use them for reading the lessons. From the about 1300 until after 1500 relatively wealthy churches might use a lectern in the form of an eagle (the symbol of St John the Evangelist), with outspread wings, standing on a globe. Such lecterns could be in cast brass or in carved wood, which was cheaper. Fewer than 20 wooden lecterns of this date survive in England and Wales.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Chestnut and oak, carved |

| Brief description | Lectern in the form of an eagle, made in the late 15th century, of carved oak and chestnut, with a stand of a later date, possibly Wales |

| Physical description | Lectern in the form of an eagle. Carved chestnut, the outspread wings terminating in a ledge for the book; the legs and feet a wrought iron stand on a circular flattened ball which rests in turn on a fluted column of oak, fixed in to an X shaped base and supported by four carved brackets. Late 15th or early 16th century; the stand early 17th century. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Given by Messrs. J. Wippell and Co. Ltd., Exeter |

| Object history | From the chapel of Chirk Castle, Denbigshire which dates from the tome of Edward I. Illustrated in the report of the annual meeting of the Cumbrian Archaeological Society held at Oswestry on Aug. 21st 1893, page 4. Gift from Messrs. J. Wippell and Co Ltd., 55-56 High Street, Exeter. Notes from R.P. 22/158 21/12/21 Minute sheet H C Smith to Colonel Strange recommends the acquisition of this "example of a rare object" - a wooden reading desk or lectern in the form of an eagle. He dates the oakstand 1620 to 1640 and believes the bird of chestnut wood to be of the same date based on the general character of the carving. According to Dr Cox (English Church Furniture) the use of the eagle-lectern arrived in the 17th century. The style of the work and the colour of the wood points to the Low Countries as the origin. This lectern is stated to have come from "a church in Dorsetshire". Smith believes it is of English workmanship and supports acquisition of "so rare and interesting an object". 22 December 1921 E F Strange Minute paper supports acquisition. Its importance "is not diminished by the fact that its origin presents an interesting problem". Strange suggests that the eagle was not designed to stand on its present pedestal (which is too low and entirely unrelated in its construction). The ball "seems to have been made to fit into a socket and perhaps turn". He refers to such a mounting in the 15th century lectern of the Church of Puligny (Cote d'Or) - photo 1585-93 in the Library. 4 January 1922 letter Wippel & Co. to V & A Reports that the lectern is to be offered as a gift rather than for purchase as originally suggested. The gift is in recognition of the fact that the Museum is "of the utmost practical utility to firms engaged in ecclesiastical and industrial art - - For the training and inspiration of designers and for purpose of reference". In a letter from the Department of Woodwork deputy keeper to one Canon Handisyde of Selsey (Sussex) various information about the lectern is given. The lectern was one of the fittings of the private chapel of Chirk Castle, Denbighshire. In 1878 the chapel was described (J.B.A.A., XXXIV, pp.197-8) as "filled with the peculiar fittings of a domestic chapel of the time of Charles I", pulpit, reading-desk and other ecclesiastical furniture being "within the chancel arch", but "in a very dilapidated condition". In 1894 this piece ("one of the earliest of modern eagle lecterns") was figured beyond doubt of identity (Arch. Cambr (5), XI, 1894, at p. 137 - see also below). The chapel was then in course of restoration by Sir Arthur Blomfield (d. 1899). The egress of the lectern perhaps dates from then. In 1922 the lectern was offered for £35, and then as a gift, to this Museum by Messrs. J. Wippell & sons, Ltd., the church furnishers of Exeter. The erroneous statement then made that the lectern came "from a church in Dorsetshire" was run to earth by Mr H. Clifford Smith, of this Department (192/1922 and Reg.). Information from Sarah Kay, Chirk Project curator, Sept 2006: Journal of the Cambrian Archaeological Association of 1894, p133 "The Chapel at the south-east corner of the quadrangle is of Edward I's time, and has some good carving of the Queen Anne Period, and one of the earliest of modern eagle lecterns". A drawing of the lectern is also illustrated on p136. In 1630 the first popular translation of the Bible into Welsh was published "chiefly" at the "cost and care" of Sir Thomas Myddelton the Elder (d.1631) who has bought the Marches Lordship of Chirk in 1595 and was Lord Mayor of London in 1614. The preface describes him as one of "certain pious and honourable citizens of London". (Margaret Mahler's translation in Chirk Castle, 1912, p. 143). The spread-eagle and ball of chestnut wood and late medieval date were fitted early in the 17th century over a shaft of Laudian and apparently oak, with stopped fluting, on a scrolled cruciform base. It is possible, argues the deputy keeper that the original 15th century lectern had been sawn off its stand, perhaps as part of iconoclastic activity, and was then mounted on a new shaft in Laudian times. Cox (1915) however argues (p.165) that eagle lecterns were not generally the target of iconoclasts. The documented concealment of a number of brass eagle lecterns and the tradition told of the Salcombe Regis (Devon) wooden eagle lectern, removed to safety during the Commonwealth, then rediscovered in the thatched roof of another building in 1849 and restored to the church (letter, CL, Oct 19th 1951), suggest that their intrinsic value (rather than association with traditional religion) led to them being hidden during periods of social instability such as the Civil Wars. Christopher Hussey, Country Life, September 2, 1951 "Chirk Castle, Denbighshire" suggests (p.982) that the chapel (originally15th century) was probably moved to the SE corner in about 1600. The 2001 National Trust guidebook by Richard Dean (p.30) says that the present chapel may be dated to the late14th or early 15th century." Seventeenth- century owners added a mass of wooden fittings, now destroyed. The second Sir Thomas Myddelton, a parliament man but no puritan, ordered an organ in 1632 at a cost of £150, its many-towered organ case being a spectacular piece of carved and gilded architecture. Under the 2nd Baronet, the 1670s saw the installation of pews, a reading desk, a pulpit, a fitted altar and a gallery. The gallery, decorated with carved scrolls and fretwork by Dugdale, was erected against the half-timbered west wall..." The chapel is not included in the1612 inventory, but in 1632 Sir Thomas Myddelton declined to contribute to a rate for the repair of Chirk parish church by alleging that "the lordship of Chirk is a Lordship Marcher and hath enjoyed time out of mind a free Chapel endowed with tythe of all ancient demesne lands of the castle." The Torrington Diaries of Hon. John Byng (1781-1794) record that "the chapel is a poor thing, & not kept in that order, that the house of God shou'd be..." |

| Historical context | Cox and Harvey (1908) note "It was customary in the Middle Ages to have in chancels or quires a desk or lectern from which the Gospel was read; these were usually of wood or metal, and moveable, more rarely fixed and of stone. The practice of the reformed Church has been to bring them out into the body of the church, and to use them for reading the Lessons, and it is in the nave, just west of the chancel arch, that the comparatively few medieval specimens which have come down to us are now to be found...eagle lecterns [as opposed to single or twofold or fourfold desks on a pillar] date from the 15th and 16th [centuries]. The use of the eagle lectern seems to have revived in the 17th cent., and many examples are of that period, the best of which are those of the cathedral churches of Wells (1660), York (1666), and Lincoln (1667)...Wooden eagles are somewhat less frequent than those of brass." They record wooden eagle (or pelican) lecterns at: East Leake, Notts., Leighton Buzzard 14th cent (Beds), Bledlow (Berks), Sparsholt 14c (Berks), Astbury (Cheshire), Phillack (Cornwall), Bigbury (Devon), Ottery St Mary (Devon), Midleton (Hants.), Winchester, Wheathampstead (Herts.), Wiggenhall (Norfolk), East Brent (Somerset), Monksilver (Somerset), Leverington (Suffolk), Laughton-en-le-Morthen (Yorks). Cox (1915) says that wooden lecterns were probably commoner than brass in the Middle Ages, though now [1915] only about 20 survive against about 50 brass. The lecterns at Bledlow and Monksilver have both been remounted, one on a new shaft and base, the latter to the chancel screen. That in St Thomas's Exeter was 'supplied with feathers' in 1847, having been featherless originally. He points out that the carvers could easily produce unexpected effects in wood, which may explain some of the odd details seen on eagle/pelican lecterns. Tracy (2001) says that wooden eagles imitating latten ones from Dinant, [probably] produced in Namur and exported to England "are quite common in English Churches". He also suggests that the conventional medieval treatment of carving and 'fierce hieratic pose' prevailed into the early Baroque period, while late 17th century eagles display more naturalistic features. Other carved oak eagle lecterns: Oak 201 x 99cm; South Netherlands c1600, on a scrolling base (Sothebys London 9/7/2015 lot 102 estim. £6-8,000) |

| Summary | This lectern came from Chirk Castle, Denbighshire, Wales, where it stood in the private chapel until the late nineteenth century, when the chapel was refurbished. The eagle's legs and the stand are later than the eagle, probably added in the early seventeenth century when Sir Thomas Myddelton, the new owner of Chirk Castle redecorated the chapel. It was customary in medieval churches to place a desk or lectern in the chancel or choir, from which the gospel was read. These were usually of wood or metal, and moveable. After the Reformation it was more common to bring them out into the nave or body of the church, and to use them for reading the lessons. From the about 1300 until after 1500 relatively wealthy churches might use a lectern in the form of an eagle (the symbol of St John the Evangelist), with outspread wings, standing on a globe. Such lecterns could be in cast brass or in carved wood, which was cheaper. Fewer than 20 wooden lecterns of this date survive in England and Wales. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | W.2:1, 2-1922 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | March 31, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest