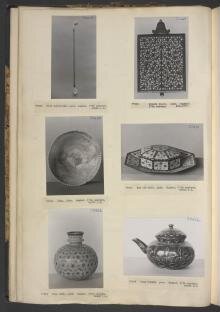

Wand of Office

17th century (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

The exact function of this object made within the Mughal empire in the late 17th century is uncertain, although it may have been a wand of office. It has been expertly fashioned from light green and white nephrite jade. The cylindrical shaft is made from a single piece of light green nephrite jade with a terminal in white nephrite in the form ofan open flower. The orange-red faceted paste stone set into its centre is probably a later replacement for an original ruby. At the other end two buds emerging from a curled leaf frond in white nephrite are attached to a section carved as a four-twist spiral. Both terminals have been joined to the main shaft by later, dark green enamelled silver mounts.

It was previously owned by the notable collector of Mughal jade and rock crystal objects, Colonel Charles Seton Guthrie who sold it with other objects from his collection to the Indian Museum in Leadenhall Street, London, in 1868. They were all transferred to the South Kensington Museum, later renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum, in 1879.

It was previously owned by the notable collector of Mughal jade and rock crystal objects, Colonel Charles Seton Guthrie who sold it with other objects from his collection to the Indian Museum in Leadenhall Street, London, in 1868. They were all transferred to the South Kensington Museum, later renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum, in 1879.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Nephrite jade, enamelled silver mounts, set with a glass imitating ruby. |

| Brief description | A wand of office or a back-scratcher, white and green nephrite jade, carved flower head and a bud handle, later mounts and paste, Mughal empire, c. 1650 formerly in the Guthrie Collection |

| Physical description | The shaft is cylindrical and fashioned from a single piece of light green nephrite jade and it has a terminal carved in white nephrite as an open flower that has an orangey red faceted paste stone set into its centre. At the other end is a carved handle (possibly) fashioned in white nephrite as two buds emerging from a curled leaf frond attaching to a section carved as a four-twist spiral. These ends have been joined to the main shaft via later, dark green enamelled silver mounts. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | Mughal: period of Shah Jahan,possibly This object was originally in the Guthrie collection and was purchased for the sum of £11-0-0, when he sold 81 of his objects to The India Museum in 1868. It was subsequently transferred to The South Kensington Museum (later renamed The Victoria & Albert Museum) in 1879. Charles Seton Guthrie was an important collector of eastern coins and Mughal Empire jade and rock crystal objects. He was the second son of Scottish parents, both of whom were from noble and landed families, and his father worked for the East India Company in Calcutta. Guthrie most probably developed his interest in jade and rock crystal when he studied geology as a 17 year old cadet in 1825 in Addiscombe, and he joined the Bengal Engineers in 1828. Through his family’s established connection with the Inglis and Lister families, he became acquainted with Harry Inglis and his Anglo-Indian wife Sophia (nee Lister). He may well have received gifts of objects that Harry had acquired as proceeds from his Indian military campaigns. Harry was the son and heir of George Inglis who owned Inglis & Co., a large Indian trading company. During his time in India, Charles Guthrie enhanced his collections with acquisitions financed by his army pay and also income from properties in his late mother’s estate. He subsequently retired at the honorary rank of Colonel in 1857, although he returned to England in 1855, at the same time as Harry and Sophia, due to having 2 years of accumulated leave. Following Harry’s death in 1860, his embalmed body was returned to India, accompanied by Sophia and Charles, where it was interred in an above-ground tomb. Sophia inherited Harry’s vast estate, which almost certainly contained many fine jewels and Mughal objects. Sophia began living together with Charles in Calcutta, bearing him a son in 1862. Following a financially significant arrangement being agreed by Sophia with Charles, the two eventually married in 1863 with the family returning to England a short time thereafter. Sophia died in 1866, with Charles being named as an executor with instruction to liquidate her un-itemised English estate which included “jewels, trinkets and shawls”. Soon thereafter, in 1868, Guthrie sold part of his collection of jade and rock crystal objects to The India Museum and his large coin collection to a museum in Germany. Colonel Charles Seton Guthrie died in 1874 and the remainder of his collections was sold at auction, in accordance with the terms of his will, with many objects finding their way into other important collections and then subsequently to the museum. |

| Summary | The exact function of this object made within the Mughal empire in the late 17th century is uncertain, although it may have been a wand of office. It has been expertly fashioned from light green and white nephrite jade. The cylindrical shaft is made from a single piece of light green nephrite jade with a terminal in white nephrite in the form ofan open flower. The orange-red faceted paste stone set into its centre is probably a later replacement for an original ruby. At the other end two buds emerging from a curled leaf frond in white nephrite are attached to a section carved as a four-twist spiral. Both terminals have been joined to the main shaft by later, dark green enamelled silver mounts. It was previously owned by the notable collector of Mughal jade and rock crystal objects, Colonel Charles Seton Guthrie who sold it with other objects from his collection to the Indian Museum in Leadenhall Street, London, in 1868. They were all transferred to the South Kensington Museum, later renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum, in 1879. |

| Bibliographic reference | The Indian Heritage. Court life and Arts under Mughal Rule London: The Victoria and Albert Museum, 1982 Number: ISBN 0 906969 26 3

pp. 118-119, no. 358, Robert Skelton |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 02606(IS) |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | March 15, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest