Corbel

Corbel

ca. 1125-1150 (made)

ca. 1125-1150 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

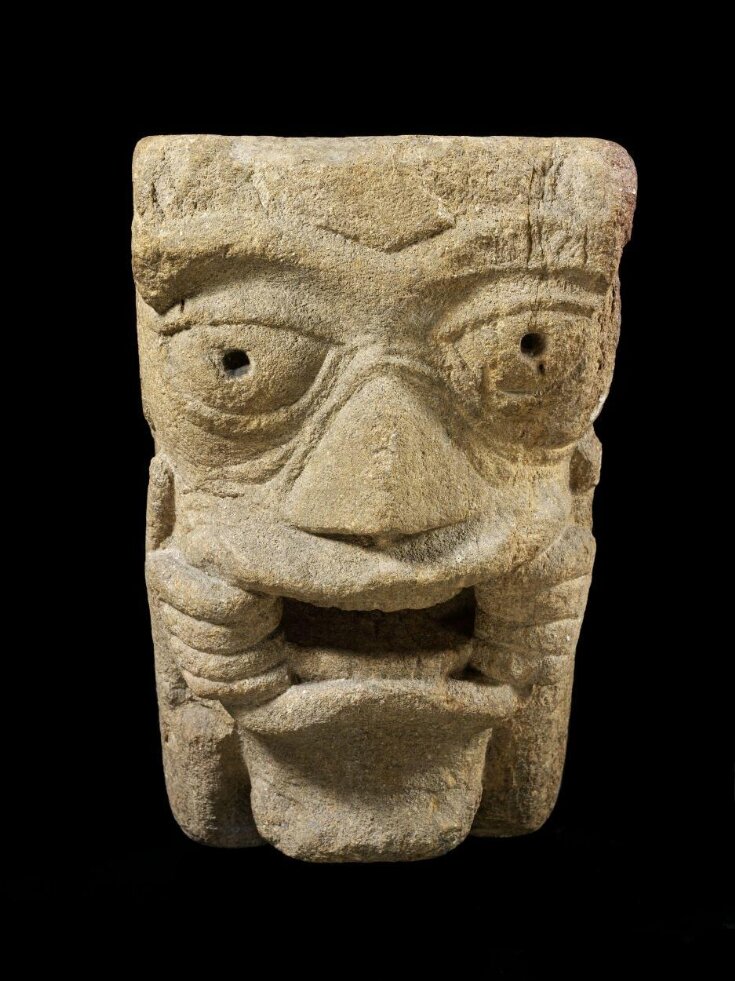

Corbels supported the eaves of roofs or arches. Here the ornament did not always represent sober religious stories. Face-pulling figures were a familiar sight, although it is hard to know what exactly they meant to medieval viewers. A figure like this might be comic or threatening.

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Corbel (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Carved sandstone |

| Brief description | Corbel, sandstone, grotesque head, England, 1120-1150 |

| Physical description | The corbel is carved as the head of a grotesque figure. The bulbous eyes with thick lids have had their pupils drilled, the mouth is stretched open with two hands. On the left side are four decorative curling scrolls placed one above the other, on the right side are another four scrolls two of which face each other. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | The provenance of this corbel is unknown. Bought from J. Hunt in 1946 Historical significance: It is from the ornamented corbels of the eleventh and twelfth centuries such as A.4-1946 that the use of the word corbel has gained an association with grotesque ornamentation. |

| Historical context | A corbel is a projection of stone, timber or other constructional material, jutting out from (not merely attached to) the face of a wall, usually supporting a superincumbent weight. Although ornamentation is not essential to the principle function of a corbel, one of the main features of Romanesque sculpture is the marriage of architecture and ornament and the collaboration of mason and sculptor to create highly decorated functioning structure of which this corbel is an excellent example. The sculptor and mason were, at times one and the same person (Zarnecki 1985). The idea of the carved corbel came to England from the continent and soon became a favourite feature of English Romanesque architecture. As both internal and external architecture, corbels can be found supporting tympana (Ely) arches (Cumnor Berks.) in a corbel-table (Kilpeck, Ely and Winchester Cathedral) in which a row of carved corbels run just below the eaves. They can support parapets on bell towers as at (Hinton-in-the-Hedges Northants.) and occasionally, they are used as wall decoration in a similar way to a string-course. The scale and presence of the work , together with the angle of the head, suggest that it was placed high up. Carved corbels often demonstrate considerable wit and imagination on the part of the mason. The faces of monsters animals and humans, many with gaping mouths, adorned the corbels of post-conquest churches and cathedrals. An example showing the same type of figure as A.4-1946, pulling at the sides of his mouth with his hands, can be seen on the outside of the south transept of Winchester Cathedral (G.Zarnecki English Romanesque Sculpture 1066-1140 London 1951, pl.33) and there are two examples at Kilpeck (G.R.Lewis, Illustrations of Kilpeck Church, Herefordshire, London, 1842 pls.6 and 9): Paul Williamson considers A.4-1946 to be later than the Winchester corbel which was executed soon after 1107 and proposes that it should be dated more closely to the Kilpeck examples of around 1150. The corbel is also close in type to a beak-head from the Cathedral of Old Sarum now in Salisbury museum from about 1140 (G.Zarnecki English Romanesque Sculpture 1066-1140 London 1951, pl.43) . Other examples of humans distorting their own mouths can be found in a tongue-puller corbel SS Andrew & Mary, Grantchester and a mouth-puller at St Andrew's, Steyning. The exaggerated, insect-like eyes are found over a wide area in the south west England up to about 1160 and do not allow exact localisation, the sandstone used is of a common type. The curling scroll decoration at the sides of the corbel ultimately derives from Cordoban models: roll corbels with this kind of decoration are first seen in Cordoba in the eighth century. By the eleventh century , when this type of corbel had spread to western France, the scroll-work had become more refined and secondary to the shape of the corbel. (K. Watson 'French Romanesque and Islam: Influences from Al-Andalus on architectural decoration' in Art and Archaeology Research Papers 2 December 1972, pp.1-27) Weir and Jerman cite this corbel in their proposition that the face-puller type is linked to images of overt sexuality which can adorn medieval churches. They claim that mouth-pulling faces without bodies are a shorthand symbol for other more explicit forms of exhibitionism which the observer could infer from other forms on the corbel table. |

| Production | South West England |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Corbels supported the eaves of roofs or arches. Here the ornament did not always represent sober religious stories. Face-pulling figures were a familiar sight, although it is hard to know what exactly they meant to medieval viewers. A figure like this might be comic or threatening. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | A.4-1946 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | January 12, 2006 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest