Tunic

670-870 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Textiles were made for and used by the widest possible segment of the population of late Roman and Byzantine Egypt. They were made commercially in small workshops and by individual weavers. While most textile decorations were made in large numbers, many must have been individually ordered both for dress and the household.

The construction of the tunic was similar for men, women and children — one piece of cloth was folded over the shoulders and sewn together down the sides. Around the 5th century, tunics begun to be made in two or three pieces, with a horizontal seam in the centre positioned slightly above the waist. A belt, woven, braided, knitted or tablet woven, was worn to hold the folds of the garment in place. The bands and stripes that commonly decorate Coptic tunics are possibly Roman in derivation.

The construction of the tunic was similar for men, women and children — one piece of cloth was folded over the shoulders and sewn together down the sides. Around the 5th century, tunics begun to be made in two or three pieces, with a horizontal seam in the centre positioned slightly above the waist. A belt, woven, braided, knitted or tablet woven, was worn to hold the folds of the garment in place. The bands and stripes that commonly decorate Coptic tunics are possibly Roman in derivation.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

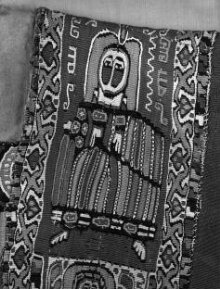

| Materials and techniques | Plain woven wool, with appliqué ornaments tapestry-woven in coloured wool and linen on linen warps |

| Brief description | Red woven linen and wool, 670-870, Egyptian; tapestry woven, applied decorations in coloured wools, with figures |

| Physical description | Tunic of red wool, with narrow white vertical stripes at the sides and below the neck; applied tapestry-woven ornaments in coloured wools and undyed linen thread on linen warps. As follows: (1) Two shoulder-bands, clavi, with standing haloed figures, floral devices and busts; the large pendant medallions, orbiculi, each contain a half-length figure; (2) two large roundels below, segmenta, and two on the shoulders, each containing a seated figure in the middle, surrounded by floral ornament partly issuing from four vases; (3) two large oblong panels on the sleeve, each containing a seated figure within a circle in the middle, and floral ornament and busts to the right and left. Some Greek letters. All these ornaments have borders of floral stems on a white ground, with a polychrome geometrical edging on either side. A small tapestry band, sewn across at the neck, has pairs of birds in circles. S-spun wool, probably Egyptian. The tunic is made up from several pieces: seam at the waist, and across the sleeves (the seam down centre front is secondary and probably from the time of discovery). The wrists and sides of each sleeve end in selvedges. The size of the tunic is huge with narrow sleeves. The hem is torn and raw; the side seams are turned in and stitched up (now unpicked); the sleeves are open under the armpit and the sewn tuck around waist has been unpicked. The tunic is stained and decayed in a number of places on the back and missing its two back roundels (only discolouration and stitch marks remain). |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | Objects 275-1891 to 303-1891 purchased from Monsieur Phocion Tano. |

| Historical context | General This tunic is a good example of new features in the cut and shaping of garments. The Arabs conquered Egypt in 641, yet the long standing traditions of Roman and Byzantine dress were maintained alongside Arab fashions. This tunic is made in several pieces, instead of one and has shaped neck-opening in place of the horizontal slit of earlier periods. The ornaments are no longer woven into the tunic but are additional ornaments which were supplied by a specialist tapestry-workshop and sewn on. Here they comprise shoulder-bands, neck-bands, sleeve-bands and originally six large medallions for shoulders and skirt (only the front skirt medallions have survived), in a style rather coarsely imitated from the most luxurious Byzantine silk fabrics of the 8th to 9th century. The ornaments come from at least two different sets. In its present state the tunic is long enough for a woman, but traces of a low, very deep waist-tuck show that it was shortened to be worn by a man. In the tapestry of the shoulder-bands is the name of God, Allah, in Arabic script. However, one letter is missing (the first freestanding one) and it is also woven mirror image. This could be due to faulty original design or the weaver might not to have been familiar with the word. Incorporating the word Allah was common at this time, both for reasons of faith and for purely decorative purposes. At this point, tapestry-woven decoration was bought separately from shops, so anyone of any faith could buy whatever took his or her fancy. Construction Tunics, almost straight, shirt-like dresses, reaching to the knees or somewhat longer, appear to have been in fashion among several groups of citizens in the Roman empire from 100-1000 AD. This type of dress was also adopted by the Egyptians. The construction of the tunic was similar for men, women and children - it was made in one piece which was folded over the shoulders and was sewn together along the sides. Around the fifth century tunics begun to be made in two, or more often three, pieces with a horizontal seam in the centre positioned slightly above the waist. A belt, woven, braided, knitted or tablet woven, was worn to hold the folds of the garment in place. The bands and stripes that commonly decorate Coptic tunics are possibly Roman in derivation. Less certain is the origin of the decorated squares, circles and ovals that are an equally common features of Coptic tunic ornamentation. On tunics, the ornaments were often positioned to lie above the shoulders and in front of the knees of the wearer, vulnerable points, susceptible to disease and crippling injuries. One suggestion is that the positioning of these ornaments originated in a widespread belief that glances from the eyes of certain people could cause harm. Defenses against the evil eye are of several types: designs that are in the form of an eye, or designs of such fascination or complexity that they trap the eye, or gestures such as an upraised hand. All are found in Coptic ornamentation. Textile production Textiles were made for and used by the widest possible segment of the population of late Roman and Byzantine Egypt. They were made commercially in small workshops and by individual weavers. While most textile decorations were made in large numbers, many - both for costumes and the household - must have been individually ordered. Since a great portion of surviving textiles are of linen, the importance of wool in the Roman and Byzantine centuries remains largely undervalued by scholars. Papyri indicate that wool clothing was very much in use, but it rarely survives. Use Tunics were woven from sleeve to sleeve in one piece with integral tapestry-woven ornaments (see T.7-1947), but from around the fifth century tunics were also made in two, or more often three, pieces with a horizontal seam in the centre positioned slightly above the waist, and from at least the Arab conquest (AD 639-642) there was a gradual decline in integral ornaments. This one has been made up from several pieces stitched together. All the tapestry woven decorations are applied, and on the sleeves, it is even cut and tucked into the seam, turning the straight woven sleeves of 'Coptic' style into shaped and narrowly fitted sleeves of the Arabic fashion. A sewn tuck at the waist fitted the tunic to the individual, but here the tuck has been let out and the shoulder bands are now applied over the tuck area. However, the area clearly shows changes in colour tone where the body fluids correspond with the original tuck - the tunic was lengthened by undoing the waist tuck and shoulder bands re-attached at some time after the tunic was excavated in the late 19th century (not at the time of the burial). One tunic, usually very simple, was worn as an undergarment; another, decorated with ornaments and usually wider, was worn over it. In the 3rd century the custom of burying the dead fully clothed and wrapped in multiple layers of fabrics began. Although found in graves, only a small number of tunics were actually made as funerary clothing and shrouds. Much of the clothing of the corpses was not new, and all the padding and wrapping were done with discarded and otherwise available textiles. There are also examples of tunics in graves that have never been made up, maybe suggesting a sudden death or a wish to dress the dead in new clothing, it not being deemed important to finish the garment. It is also evident that re-use was practised. A new tunic might be used as background for old, well-liked and costly decorations of which this tunic might be an example. Most recent and useful scholarly publication Frances Pritchard. Clothing Culture: Dress in Egypt in the First Millenium AD. Manchester: Whitworth Art Gallery, 2006. |

| Production | Site unrecorded; probably Akhmîm |

| Summary | Textiles were made for and used by the widest possible segment of the population of late Roman and Byzantine Egypt. They were made commercially in small workshops and by individual weavers. While most textile decorations were made in large numbers, many must have been individually ordered both for dress and the household. The construction of the tunic was similar for men, women and children — one piece of cloth was folded over the shoulders and sewn together down the sides. Around the 5th century, tunics begun to be made in two or three pieces, with a horizontal seam in the centre positioned slightly above the waist. A belt, woven, braided, knitted or tablet woven, was worn to hold the folds of the garment in place. The bands and stripes that commonly decorate Coptic tunics are possibly Roman in derivation. |

| Associated object | 168-1892 (Part) |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 291-1891 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 12, 2005 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest