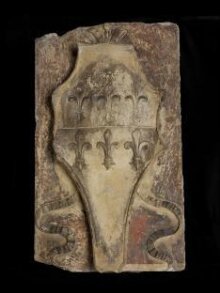

Saint George and the Dragon with two armorial reliefs

Relief

ca. 1500 (made)

ca. 1500 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

These reliefs were originally set in the external wall of a house near the Ponte dei Baretteri, Venice, where they were seen and vividly described by the celebrated art critic John Ruskin (St Mark's Rest, 1877-84). He noted the 'most consummate precision of artistic skill. Look at the strap of the stirrup- at the little delicatest line of the spur, - can you think they are stone? don't they look like leather and steel? His flying mantle. - is it not silk more than marble?'

There are other examples of similar reliefs surviving in Venice and they seem to have been installed on houses owned by prominent members of the Scuola degli Schiavoni, the religious guild run by Dalmatians (Slavs) for the benefit of visiting seamen from their homeland. The Dandolo, whose arms appear on the two shields, were one of the richest and most important Venetian noble families.

There are other examples of similar reliefs surviving in Venice and they seem to have been installed on houses owned by prominent members of the Scuola degli Schiavoni, the religious guild run by Dalmatians (Slavs) for the benefit of visiting seamen from their homeland. The Dandolo, whose arms appear on the two shields, were one of the richest and most important Venetian noble families.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 3 parts.

|

| Title | Saint George and the Dragon with two armorial reliefs (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Carved and painted Istrian stone |

| Brief description | Saint George and the Dragon with two armorial reliefs. |

| Physical description | Saint George and the Dragon with two armorial reliefs. The central relief which is recessed within a moulded border, shows St George in right profile on a rearing horse. The saint is armed and his cloak blows out behind him. He thrusts his lance into the mouth of the dragon , whose tail is curled around the rear legs of the horse, and head is turned back towards the saint. On the right, rocky ground rises precipitously, and on a platform at the top is the small figure of the princess with hands raised. The two side panels are uniform, each shows a shield, represented as though suspended by ribbons from a nail, charged with the arms of the Dandolo family (per fess, six fleurs-de-lys, 3 and 3, counter-charged). The upper parts of the wing of the dragon on 53-1884 and the left corners of the shield on 53A-1884 have been chipped. The surface of 53-1884 has been unevenly cleaned, and areas of discolouration round the figures are perhaps indicative of pigmentation. Some traces of red paint (date uncertain) occur in the background. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | The relief was originally set in the external wall of a house near the Ponte dei Baretteri in Venice. It is described in its original position by Ruskin in his St Mark's Rest (The Works of John Ruskin, ed. E.T. Cook and A Wedderburn, xxiv, London, 1906, pp. 245-7). A water-colour by A. Alessandri in the Museo Correr shows the relief in the location described by Ruskin. An undated cutting from an unidentified Venetian paper (presumably 1884) throws some light on how the work came to the Victoria and Albert Museum. According to the cutting, the relief was acquired by Consiglio Ricchetti in December, 1883 and was then resold by him to Sir Henry Layard (acting on behalf of the South Kensington Museum) . With the agreement of Richetti offered the relief to the museo Civico, which declined the offer. The relief, which was then sent to London on 26th January 1884. The matter was referred to the Commissione Conservatrice dei Monumenti, which also refused to provide money for the purchase, but held that the export was illegal under an Austrian law of 1819 which had not been repealed. Representatives of Consiglio Ricchetti and of the firm responsible for shipping the relief to London were subsequently fined a total of 14,800 lira. This verdict was reversed on appeal. Pope-Hennessy proposes that the publication of Ruskin's description of the relief between (1877-1884) prompted the acquisition of the piece . Historical significance: The passage in which Ruskin described the relief is as follows: "Here is St George indeed! our own beloved old sign of the George and Dragon, all correct; and, if you know your Seven Champions, Sabra too, on the rock, thrilled witness of the fight. And see what a dainty St George too! Here is no mere tailor's enthronement. Eques, ipso melior Bellerophonti, - how he sits! - and how he holds his lance! how brightly youthful the crisp hair under his light cap of helm, - how deftly curled the fringe of his horse's crest, - how vigorous in disciplined career of accustomed conquest, the two noble creatures! This is Venetian fifteenth century work of finest style. Outside-of-house work, of course...Though the figure is still symbolical, it is a symbol consisting in the most literal realization possible of natural facts. That is the way , if you care to see it, that a young knight rode, in 1480, or there-abouts. So, his foot was set in stirrup, - so his body borne, - so trim and true and orderly everything in his harness and and his life: and this rendered, observe, with the most consumate precision of artistic touch. Look at the strap of the stirrup, - at the little delicatest line of the spur, can you think they are stone? don't they look like leather and steel. His flying mantle, is it not silk more than marble? That is all in the beautiful doing of it: precision first in exquisite sight of the thing itself, and understanding of the qualities and signs, whether silk or steel; and then, precision of touch, and cunning in use of material, which it had taken three hundred years to learn. Think what cunning there is in getting such an edge to the marble as will represent the spur line, or the strap leather, with such solid under-support that from 1480 until now, it stands rain and frost! And for knowledge of form,-look at the way the little princess' foot comes out under the drapery as she shrinks back. Look at it first from the left, to see how it is foreshortened, flat on the rock ; then from the right, to see the curve of dress up limb...Finally, see how studious the whole thing is of beauty in every part, - how it expects you also to be studious. Trace the rich tresses of the Princess' hair, wrought where the figure melts into shadow;- the sharp edges of the dragon's mail, slipping over each other as he wrings neck and coils and tail; - nay, what decorative ordering and symmetry is even in the roughness of the ground and rock! And lastly, see how the whole piece of work, to the simplest frame of it, must be by the sculptor's own hand: see how he breaks the line of his panel moulding with the Princess' hair, with St George's helmet, with the rough ground itself at the base;- the entire tablet varied to it's utmost edge, delighted in and enobled to its extreme limit of substance. Here, then, as I said , is the top of Venetian sculpture-art." |

| Historical context | Perocco in "Tutta la pittura di Carpaccio" noted that reliefs of St George and the Dragon were commonly installed on houses bequeathed to the Scuola degli Schiavoni or owned by prominent members of the school. The Schiavoni were an important and wealthy trading colony of Dalmatian merchants who built their own scuola, or confraternity. The Venetian Republic always placed great importance on trade relations with Dalmatia, its neighbour across the Adriatic Sea. The rapport with the Dalmatian Slavs (known to the Italians as Schiavoni) became still more intense at the beginning of the fifteenth century, when coastal regions of Dalmatia came under the power of the Republic. In 1451, the Schiavoni in Venice united to form a guild under their patron saints, Saint George, Saint Tryphone, and Saint Jerome. Then, in the early sixteenth century, the Dalmatian community built its own Guild Hall in Castello. The guild's official name was Scuola Dalmata dei Santi Giorgio e Trifone, although the Scuola is commonly known to Venetians as Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni. Markham Schulz cites this relief as being of a type which could have informed a work by Giambattista Bregno. She suggests that the image of George and the Dragon was an emblem of the Benedictine monastery and as such was used to identify its property throughout the city of Venice. She goes on to state that form a work by Irmgard Fees "We know that the convent of St Giorgio owned the houses at the Ponte dei Baretteri from which the London relief was prised". At the time of acquisition the arms on the lateral panels were thought to be those of the Doge Pietro Ziani, however the shields are now considered to bear the arms of a member of the Dandolo family. The family were one of the most illustrious patrician families of Venice, of which the earliest recorded member was one of the electors of the first doge in 697 AD. They rose quickly to prominence when expansion from the lagoons to the mainland began, by the 11th century they boasted considerable wealth and by the 12th (when the branches of San Luca, San Severo, and San Moisè can already be distinguished) they were competing for the highest posts in church and state. The family gave Venice four Doges : Enrico, Doge of the Republic of Venice 1192-1205, Giovanni 1280-1289, Francesco 1329-1339 and Andrea 1343-1354. Enrico was particularly notable for his re-establishment of Venetian authority over Dalmatia, the sacking of the Dalmatian city of Zara and his promotion of the Fourth Crusade, which led to the overthrow of the Greek Byzantine Empire and the aggrandizement of Venice. The full arms of Dandolo are per fess argent and azure, six fleurs-de-lys, 3 and 3, countercharged. |

| Production | Dated by Ruskin to about 1480; Maclagan and Longhurst state that the Italian editor of St Mark's Rest (the publication in which Ruskin described the relief) noted a similar relief on the barracks (once a monastery) on the Riva degli Schiavoni, dated 1508. Pope-Hennessy identifies this second relief as possibly being that on the Isola di San Giorgio and notes a related relief of 1496 that exists in the Campo San Zulian from which he concludes a date of late fifteenth or very early sixteenth-century. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | These reliefs were originally set in the external wall of a house near the Ponte dei Baretteri, Venice, where they were seen and vividly described by the celebrated art critic John Ruskin (St Mark's Rest, 1877-84). He noted the 'most consummate precision of artistic skill. Look at the strap of the stirrup- at the little delicatest line of the spur, - can you think they are stone? don't they look like leather and steel? His flying mantle. - is it not silk more than marble?' There are other examples of similar reliefs surviving in Venice and they seem to have been installed on houses owned by prominent members of the Scuola degli Schiavoni, the religious guild run by Dalmatians (Slavs) for the benefit of visiting seamen from their homeland. The Dandolo, whose arms appear on the two shields, were one of the richest and most important Venetian noble families. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 53 to B-1884 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 30, 2005 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest