The Real Thing

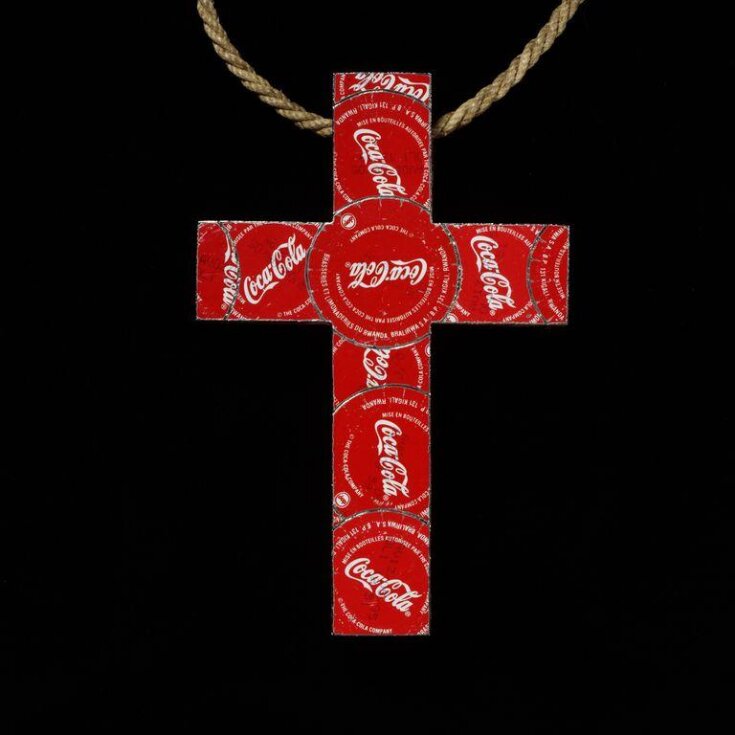

Pectoral Cross

2004 (made)

2004 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

When David Poston was asked what prompted him to make this pectoral cross from Coca-Cola bottle tops, collected from a bar in Rwanda, he posed the following series of questions.

Is there anything inherently offensive in the piece? If someone were to choose to take offence would this be because of any statement genuinely inherent to the piece or a reflection of their own position, prejudices or assumptions?

If the juxtaposition of Cross and Coca-Cola is offensive, to whom and why?

If the unconventional juxtaposition is not offensive or emotive to an individual viewer, why not?

The Coca-Cola bottle tops were collected in Rwanda for the express purpose of making the piece. Rwanda is a Christian country, an extremely poor society.

What are Coca-Cola doing in Rwanda? Are they helping Rwanda’s recovery from the events of 1994 through the development of commerce? Are they exploiting mass-marketing techniques through people’s desire to participate in a glossy romanticised life-style? What does the power of a Brand mean in markets like this?

“Coca-Colonisation”. Coca-Cola (and Pepsi Cola) can be bought in the very poorest villages in Africa, in many places dedicated fridges being supplied by the company for the presentation of their products but forbidden for any other alimentary or medical purpose.

What does the cross mean? To the moral American Christians who run Coca-Cola, to the Christians in Rwanda?

What do Coca-Cola bottle tops imply or represent? In this context, what is the significance of their coming from Rwanda?

If the juxtaposition appears to be significant, then the viewer may consider why this should be and what it implies regarding the respective meanings of the Cross and Coca-Cola symbols.

How great is the difference between the two symbols? Do they both now represent brands?

Are Christianity (or any religion) and commerce still compatible? Have they ever been?

What is “The Real Thing”?

What is real?

Does this piece have any meaning?

The Coca-Cola bottle tops were collected by David Poston in the bar of the Hotel des Mille Collines, the subject of the film, Hotel Rwanda, directed by Terry George and released in 2004. It was adapted from a screenplay written by both George and Keir Pearson. Based on real life events in Rwanda during the spring of 1994, the film stars Don Cheadle as hotelier Paul Rusesabagina, who attempts to rescue his fellow citizens from the ravages of the Rwandan Genocide. Sophie Okonedo and Nick Nolte also appear in principal roles. The film, which has been called an African Schindler's List, documents Rusesabagina's acts to save the lives of his family and more than a thousand other refugees, by granting them shelter in the besieged Hôtel des Mille Collines. Hotel Rwanda explores genocide, political corruption, and the repercussions of violence.

Is there anything inherently offensive in the piece? If someone were to choose to take offence would this be because of any statement genuinely inherent to the piece or a reflection of their own position, prejudices or assumptions?

If the juxtaposition of Cross and Coca-Cola is offensive, to whom and why?

If the unconventional juxtaposition is not offensive or emotive to an individual viewer, why not?

The Coca-Cola bottle tops were collected in Rwanda for the express purpose of making the piece. Rwanda is a Christian country, an extremely poor society.

What are Coca-Cola doing in Rwanda? Are they helping Rwanda’s recovery from the events of 1994 through the development of commerce? Are they exploiting mass-marketing techniques through people’s desire to participate in a glossy romanticised life-style? What does the power of a Brand mean in markets like this?

“Coca-Colonisation”. Coca-Cola (and Pepsi Cola) can be bought in the very poorest villages in Africa, in many places dedicated fridges being supplied by the company for the presentation of their products but forbidden for any other alimentary or medical purpose.

What does the cross mean? To the moral American Christians who run Coca-Cola, to the Christians in Rwanda?

What do Coca-Cola bottle tops imply or represent? In this context, what is the significance of their coming from Rwanda?

If the juxtaposition appears to be significant, then the viewer may consider why this should be and what it implies regarding the respective meanings of the Cross and Coca-Cola symbols.

How great is the difference between the two symbols? Do they both now represent brands?

Are Christianity (or any religion) and commerce still compatible? Have they ever been?

What is “The Real Thing”?

What is real?

Does this piece have any meaning?

The Coca-Cola bottle tops were collected by David Poston in the bar of the Hotel des Mille Collines, the subject of the film, Hotel Rwanda, directed by Terry George and released in 2004. It was adapted from a screenplay written by both George and Keir Pearson. Based on real life events in Rwanda during the spring of 1994, the film stars Don Cheadle as hotelier Paul Rusesabagina, who attempts to rescue his fellow citizens from the ravages of the Rwandan Genocide. Sophie Okonedo and Nick Nolte also appear in principal roles. The film, which has been called an African Schindler's List, documents Rusesabagina's acts to save the lives of his family and more than a thousand other refugees, by granting them shelter in the besieged Hôtel des Mille Collines. Hotel Rwanda explores genocide, political corruption, and the repercussions of violence.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | The Real Thing (assigned by artist) |

| Materials and techniques | Steel and wood |

| Brief description | Flattened steel bottle tops from Coca-Cola bottles, gathered in Rwanda, laser welded over a wooden former, England, 2004, designed and made by David Poston. |

| Physical description | Pectoral cross in the shape of a cross, made from the flattened steel tops of Coca-Cola bottles, collected in Rwanda, laser welded over a wooden former. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Gift of the Whiteley family |

| Object history | Made from Coca-Cola bottle tops, gathered in Rwanda. Purchased from the Lesley Craze Gallery at the "Collect" exhibition, V&A, January 2005 Historical significance: When asked what prompted him to make this pectoral cross from Coca-Cola bottle tops, collected from a bar in Rwanda, the artist David Poston, posed the following series of questions. “The Real Thing” is intended to ambiguous, to tease. Therefore the artist should not state the meaning of the piece but rather reflect a series of questions the viewer might address. One of the issues of interest to the artist is the extent to which questions may or may not occur to the individual viewer. Is there anything inherently offensive in the piece? If someone were to choose to take offence would this be because of any statement genuinely inherent to the piece or a reflection of their own position, prejudices or assumptions? If the juxtaposition of Cross and Coca-Cola is offensive, to whom and why? If the unconventional juxtaposition is not offensive or emotive to an individual viewer, why not? The Coca-Cola bottle tops were collected in Rwanda for the express purpose of making the piece. Rwanda is a Christian country, an extremely poor society. What are Coca-Cola doing in Rwanda? Are they helping Rwanda’s recovery from the events of 1994 through the development of commerce? Are they exploiting mass-marketing techniques through people’s desire to participate in a glossy romanticised life-style? What does the power of a Brand mean in markets like this? “Coca-Colonisation”. Coca-Cola (and Pepsi Cola) can be bought in the very poorest villages in Africa, in many places dedicated fridges being supplied by the company for the presentation of their products but forbidden for any other alimentary or medical purpose. What does the cross mean? To the moral American Christians who run Coca-Cola, to the Christians in Rwanda? What do Coca-Cola bottle tops imply or represent? In this context, what is the significance of their coming from Rwanda? If the juxtaposition appears to be significant, then the viewer may consider why this should be and what it implies regarding the respective meanings of the Cross and Coca-Cola symbols. How great is the difference between the two symbols? Do they both now represent brands? Are Christianity (or any religion) and commerce still compatible? Have they ever been? What is “The Real Thing”? What is real? Does this piece have any meaning? The Coca-Cola bottle tops were collected by David Poston in the bar of the Hotel des Mille Collines, the subject of the film, Hotel Rwanda, directed by Terry George and released in 2004. It was adapted from a screenplay written by both George and Keir Pearson. Based on real life events in Rwanda during the spring of 1994, the film stars Don Cheadle as hotelier Paul Rusesabagina, who attempts to rescue his fellow citizens from the ravages of the Rwandan Genocide. Sophie Okonedo and Nick Nolte also appear in principal roles. The film, which has been called an African Schindler's List, documents Rusesabagina's acts to save the lives of his family and more than a thousand other refugees, by granting them shelter in the besieged Hôtel des Mille Collines. Hotel Rwanda explores genocide, political corruption, and the repercussions of violence. |

| Historical context | The Modern Church In the late Victorian period two architects turned- craftsmen, Henry Wilson and C.R. Ashbee, initiated a decisive shift towards fine craftsmanship in church silver. This led to a sharp fall in the standing of commercial manufacturers but provided a steady source of work for many designer-silversmiths that has lasted into the present day. This revival of craftsmanship came out of the Arts and Crafts movement, one of the greatest social and artistic forces of the age. Favouring small studio workshops and simplicity of form, the movement set the pattern for church silver throughout the 20th century, whether for major cathedral commissions or for parish churches. Cathedral Church of St Michael, Coventry, 1954-62 |

| Summary | When David Poston was asked what prompted him to make this pectoral cross from Coca-Cola bottle tops, collected from a bar in Rwanda, he posed the following series of questions. Is there anything inherently offensive in the piece? If someone were to choose to take offence would this be because of any statement genuinely inherent to the piece or a reflection of their own position, prejudices or assumptions? If the juxtaposition of Cross and Coca-Cola is offensive, to whom and why? If the unconventional juxtaposition is not offensive or emotive to an individual viewer, why not? The Coca-Cola bottle tops were collected in Rwanda for the express purpose of making the piece. Rwanda is a Christian country, an extremely poor society. What are Coca-Cola doing in Rwanda? Are they helping Rwanda’s recovery from the events of 1994 through the development of commerce? Are they exploiting mass-marketing techniques through people’s desire to participate in a glossy romanticised life-style? What does the power of a Brand mean in markets like this? “Coca-Colonisation”. Coca-Cola (and Pepsi Cola) can be bought in the very poorest villages in Africa, in many places dedicated fridges being supplied by the company for the presentation of their products but forbidden for any other alimentary or medical purpose. What does the cross mean? To the moral American Christians who run Coca-Cola, to the Christians in Rwanda? What do Coca-Cola bottle tops imply or represent? In this context, what is the significance of their coming from Rwanda? If the juxtaposition appears to be significant, then the viewer may consider why this should be and what it implies regarding the respective meanings of the Cross and Coca-Cola symbols. How great is the difference between the two symbols? Do they both now represent brands? Are Christianity (or any religion) and commerce still compatible? Have they ever been? What is “The Real Thing”? What is real? Does this piece have any meaning? The Coca-Cola bottle tops were collected by David Poston in the bar of the Hotel des Mille Collines, the subject of the film, Hotel Rwanda, directed by Terry George and released in 2004. It was adapted from a screenplay written by both George and Keir Pearson. Based on real life events in Rwanda during the spring of 1994, the film stars Don Cheadle as hotelier Paul Rusesabagina, who attempts to rescue his fellow citizens from the ravages of the Rwandan Genocide. Sophie Okonedo and Nick Nolte also appear in principal roles. The film, which has been called an African Schindler's List, documents Rusesabagina's acts to save the lives of his family and more than a thousand other refugees, by granting them shelter in the besieged Hôtel des Mille Collines. Hotel Rwanda explores genocide, political corruption, and the repercussions of violence. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.20-2005 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 9, 2005 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSON