Bed Hangings

1730-50 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

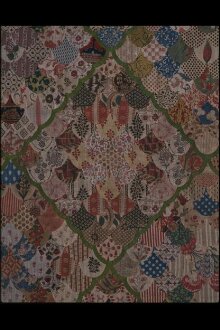

In 'piecing' or 'patchwork', small pieces of fabric are sewn together to produce a decorative design. The most enduring method in Britain is known as 'piecing over paper', where the pattern is first drawn onto paper and then accurately cut. Small pieces of fabric are then tacked round each of the shapes, before being joined together from the back using overstitch. However, in this example, each of the patches has been pieced over printed or plain linen, before being individually lined with linen. This process would have been very labour-intensive. The huge number of textiles and accuracy of the stitching supports the idea that the hangings may have been worked professionally. Over 6,400 pieces have been stitched together.

In 18th century Britain, the bedrooms of the wealthy were used for the display of luxury goods. They were a place where family members rested, servants entered and guests were entertained. Ornamental patchwork hangings reflected a household's access to a range of fashionable textiles.

Suitably lavish textiles could often be hard to come by. These hangings incorporate both British and Indian cottons. The import of decorated cottons from India was illegal at this time, but this did nothing to stem the demand. Both men and women travelled huge distances across Britain to acquire them.

In 18th century Britain, the bedrooms of the wealthy were used for the display of luxury goods. They were a place where family members rested, servants entered and guests were entertained. Ornamental patchwork hangings reflected a household's access to a range of fashionable textiles.

Suitably lavish textiles could often be hard to come by. These hangings incorporate both British and Indian cottons. The import of decorated cottons from India was illegal at this time, but this did nothing to stem the demand. Both men and women travelled huge distances across Britain to acquire them.

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 8 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Patchwork of printed cottons, linens, and fustians, and some examples of embroidered cotton (in yellow silk thread) |

| Brief description | patchwork, 1730c, English. Printed cottons, linens and fustians; clam shell design. Large curtain. patchwork, 1730c, English. Printed cottons, linens and fustians; clam shell design. Large curtain. patchwork, 1730c, English. Printed cottons, linens and fustians; clam shell design. Small curtain. patchwork, 1730c, English. Printed cottons, linens and fustians; clam shell design. Tester. patchwork, 1730c, English. Printed cottons, linens and fustians; clam shell design. Proper left valence. patchwork, 1730c, English. Printed cottons, linens and fustians; clam shell design. Proper right valence. patchwork, 1730c, English. Printed cottons, linens and fustians; clam shell design. Foot valence. patchwork, 1730c, English. Printed cottons, linens and fustians; clam shell design. Small curtain. |

| Physical description | Patchwork bed hangings of cotton, linen and fustian, some of Indian origin. Worked in the pattern now known as 'clamshell' or 'shells'. The hangings include two large foot curtains, two small head curtains, a lower valence in three parts and an upper valence. There is no surviving headcloth or coverlet. The fabrics are both dress and furnishing, and are decorated in a variety of techniques, including block-printing, painting, resist-dyeing, stencilling and embroidery. Each of the patches has a linen template and reverse. These individual patches are worked into a larger pattern of scalloped-edged diamonds outlined in green silk tape. The repetition of prints within each diamond is completely symmetrical. Although many of the prints appear to be similar, most have been used exclusively within one diamond, meaning that there is very little duplication. Each of the large curtains had 1960 pieces and each of the smaller curtains has 784. The right and left lower valences have approximately 196 each, and the foot valence approximately 172. The upper valance has 368. Each object is lined with linen and edged in a green, white and yellow silk braid. The foot curtains still have their original brass hoops and linen tapes. There is evidence that the upper valence would have been secured by tacking it to the bed with nails, as small holes can be seen at the upper edge. The lower valences are secured with silk braid ties at the upper left and right of each valence. |

| Dimensions | Bed post measurements approximately W 10.2 cm, D 9cm. Taken from the area where the valence would fit around the posts. |

| Gallery label | Patchwork bed hangings

Possibly London

1730-50

Suitably lavish textiles for domestic goods could be hard to come by. These hangings incorporate both British and Indian cottons. The import of decorated cottons from India was illegal at this time, but this did nothing to stem the demand. Both men and women negotiated directly with smugglers to acquire them.

According to a diary kept by the donor's ancestor, these hangings were made on the Bedford School Estate in London, a large housing estate that funded a charitable school for underprivileged children. Over 6,400 pieces have been stitched together.

Cotton, linen, fustian and silk

Given by Major Harlowe Turner

V&A: 242 to F-1908(20th March 2010) |

| Credit line | Given by Major Harlowe Turner |

| Object history | Given by Major Harlowe Turner. According to a diary kept by the donor's ancestor, these hangings were made for a house on the Bedford School Estate: around 13 acres of land in the parish of St Andrew, Holborn, London. Proceeds from the estate funded the Bedford School, and were also given as alms to the poor and to aid the marriage of poor women. |

| Historical context | This is the only set of chintz bed hangings from this period that survives in a public collection. They would have been created for a fashionable middling or aristocratic household. The original use of the word ‘chintz’ was for Indian cotton cloth on which a pattern was produced by hand-drawing and dyeing with mordants and resists. While there was immense enthusiasm for chintz among British consumers in the late seventeenth century, there were also many opponents to the imported Indian goods, including the weavers of wool, linen and silk. In a bid to protect British manufacturing, a law was passed in 1701 to forbid the import of dyed or printed cottons and silk from India into Britain, except for re-export. Despite this ban, the overwhelming fashion for these light, colourful textiles led the writer Daniel Defoe to comment that it had ‘crept into our houses; our closets and bedchambers, curtains, cushions, chairs and at last beds themselves were nothing but calicoes and Indian stuffs, and in short almost everything that used to be made of wool and silk’. According to a diary written by a the donor’s ancestor (Baptist Noel Turner, 1739–1826), these hangings belonged to Elizabeth and Christiana Willes, and were said to have been made for their house on the Bedford School Estate, London. The Bedford School Estate was around 13 acres (5.2 hectares) of land in the parish of St Andrew, Holborn, London. Proceeds from the estate funded the Bedford School, and were also given as alms to the poor and to aid the marriage of poor women. Although difficult to prove, such narratives suggest how the histories handed down with each intricately pieced patchwork are often as cherished as the cottons and silks that document its textile history. |

| Summary | In 'piecing' or 'patchwork', small pieces of fabric are sewn together to produce a decorative design. The most enduring method in Britain is known as 'piecing over paper', where the pattern is first drawn onto paper and then accurately cut. Small pieces of fabric are then tacked round each of the shapes, before being joined together from the back using overstitch. However, in this example, each of the patches has been pieced over printed or plain linen, before being individually lined with linen. This process would have been very labour-intensive. The huge number of textiles and accuracy of the stitching supports the idea that the hangings may have been worked professionally. Over 6,400 pieces have been stitched together. In 18th century Britain, the bedrooms of the wealthy were used for the display of luxury goods. They were a place where family members rested, servants entered and guests were entertained. Ornamental patchwork hangings reflected a household's access to a range of fashionable textiles. Suitably lavish textiles could often be hard to come by. These hangings incorporate both British and Indian cottons. The import of decorated cottons from India was illegal at this time, but this did nothing to stem the demand. Both men and women travelled huge distances across Britain to acquire them. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 242 to G-1908 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | August 19, 2005 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest