Mirror-Case of Barber-Surgeon's Instruments

1750-1850 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

From the fifteenth century onward, lacquer objects – including book bindings, pen cases, boxes, Qur’an stands, and mirrors such as this one – gained popularity in Iran, peaking in production during the nineteenth century, with the Qajar dynasty (1797-1924). The vast increase in production across a variety of objects resulted in a considerable decline in quality; however, fine specimens continued to be done by certain artists in the cities of Shiraz, Isfahan, and Tehran. Much lacquerware during the Qajar period was also influenced by the increasing import of European artefacts, resulting in a distinctive Europeanization of designs and motifs. Lacquer production continued in Iran until 1924, when the Qajar dynasty was overthrown, after which point its production became determinably unfashionable.

Writing in the early nineteenth century, Sir William Ouseley, a Persian scholar and secretary to his brother, George III’s ambassador to the court of Fath Ali Shah (ruled 1797-1834), Sir Gore Ouseley, wrote: “At Ispahan the covers of the books are ornamented in a style particularly rich; and they often exhibit miniatures painted with considerable neatness and admirably varnished….Most provinces of the kingdome are supplied by this great city with pen-cases or kalamdans, made, like the book-covers, of pasteboard, and sometimes equally beautiful in their decorations….some contain, in various compartments on the lids, ends and sides, very interesting pictures executed in the best style of Persian miniature. The common subjects are battles and hunting-parties; but they often exhibit scenes from popular romances, among which the favourite scene seems to be Nizami’s story, the Loves of Khusrau and Shirin.”

Constructed of papier-mache and sometimes wood, lacquer objects were often decorated with small-scale paintings of popular motifs like floral patterns, birds, royal scenes, and popular romances before a varnish was then applied that protected the painting and added a pleasing reflective glow. Mirrors, as seen in this surgeon's case, began to be used in Iran in the 1660s, when mirror glass began to be imported from Europe.

Writing in the early nineteenth century, Sir William Ouseley, a Persian scholar and secretary to his brother, George III’s ambassador to the court of Fath Ali Shah (ruled 1797-1834), Sir Gore Ouseley, wrote: “At Ispahan the covers of the books are ornamented in a style particularly rich; and they often exhibit miniatures painted with considerable neatness and admirably varnished….Most provinces of the kingdome are supplied by this great city with pen-cases or kalamdans, made, like the book-covers, of pasteboard, and sometimes equally beautiful in their decorations….some contain, in various compartments on the lids, ends and sides, very interesting pictures executed in the best style of Persian miniature. The common subjects are battles and hunting-parties; but they often exhibit scenes from popular romances, among which the favourite scene seems to be Nizami’s story, the Loves of Khusrau and Shirin.”

Constructed of papier-mache and sometimes wood, lacquer objects were often decorated with small-scale paintings of popular motifs like floral patterns, birds, royal scenes, and popular romances before a varnish was then applied that protected the painting and added a pleasing reflective glow. Mirrors, as seen in this surgeon's case, began to be used in Iran in the 1660s, when mirror glass began to be imported from Europe.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 30 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | papier mâché and mother of pearl |

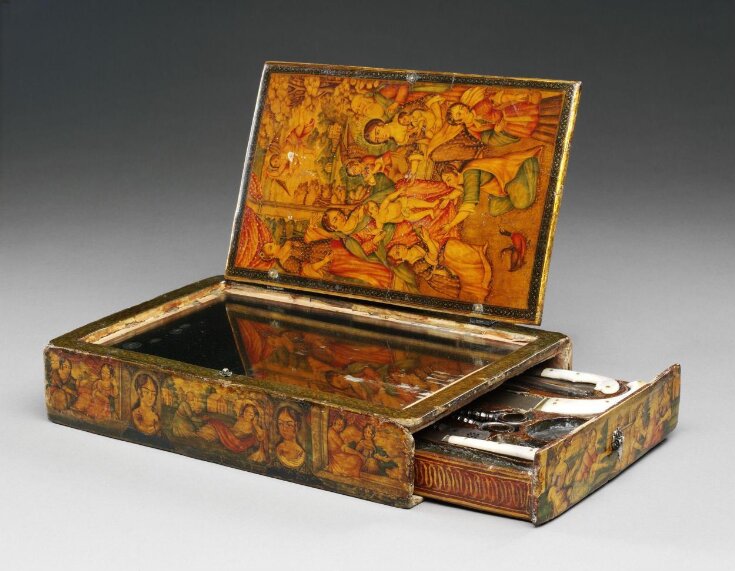

| Brief description | Mirror-case, lacquered papier mâché box, containing 27 instruments and painted with European-style scenes of women with children following Christian iconography; Iran, Zand or Qajar period, 1750-1850 |

| Physical description | Mirror-case, lacquered papier mâché box, containing 27 instruments and painted with European-style scenes of women with children following Christian iconography. There is a glass mirror under a hinged panel, and two internal drawers containing different steel instruments, some with mother of pearl handles. The instruments include knives, pliers, lancets and tweezers. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Callard gift |

| Object history | V&A Archival Record from 1929: Barber Surgeon's Case, Persian, 18th century. Papier mache decorated in colours. In the top is a door with metal hinges and catch with a mythological scene containing architecture and a group of figures, enclosed within borders decorated with foliage and floral patterns. On the inner side of the lid is another scene in a similar style, and below this is a mirror plate. The case is fitted with two trays containing 25 instruments of cut and engraved steel (ten with handles of mother-of-pearl), a mother of pearl comb with an engraved pattern of gilt scrollwork, and a sharpner. |

| Summary | From the fifteenth century onward, lacquer objects – including book bindings, pen cases, boxes, Qur’an stands, and mirrors such as this one – gained popularity in Iran, peaking in production during the nineteenth century, with the Qajar dynasty (1797-1924). The vast increase in production across a variety of objects resulted in a considerable decline in quality; however, fine specimens continued to be done by certain artists in the cities of Shiraz, Isfahan, and Tehran. Much lacquerware during the Qajar period was also influenced by the increasing import of European artefacts, resulting in a distinctive Europeanization of designs and motifs. Lacquer production continued in Iran until 1924, when the Qajar dynasty was overthrown, after which point its production became determinably unfashionable. Writing in the early nineteenth century, Sir William Ouseley, a Persian scholar and secretary to his brother, George III’s ambassador to the court of Fath Ali Shah (ruled 1797-1834), Sir Gore Ouseley, wrote: “At Ispahan the covers of the books are ornamented in a style particularly rich; and they often exhibit miniatures painted with considerable neatness and admirably varnished….Most provinces of the kingdome are supplied by this great city with pen-cases or kalamdans, made, like the book-covers, of pasteboard, and sometimes equally beautiful in their decorations….some contain, in various compartments on the lids, ends and sides, very interesting pictures executed in the best style of Persian miniature. The common subjects are battles and hunting-parties; but they often exhibit scenes from popular romances, among which the favourite scene seems to be Nizami’s story, the Loves of Khusrau and Shirin.” Constructed of papier-mache and sometimes wood, lacquer objects were often decorated with small-scale paintings of popular motifs like floral patterns, birds, royal scenes, and popular romances before a varnish was then applied that protected the painting and added a pleasing reflective glow. Mirrors, as seen in this surgeon's case, began to be used in Iran in the 1660s, when mirror glass began to be imported from Europe. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | W.87:29-1929 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | July 29, 2005 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest