M_rcan_._ti's Leap from the Opera, or the Ballet Turned into a Ball

Print

1823 (published)

1823 (published)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

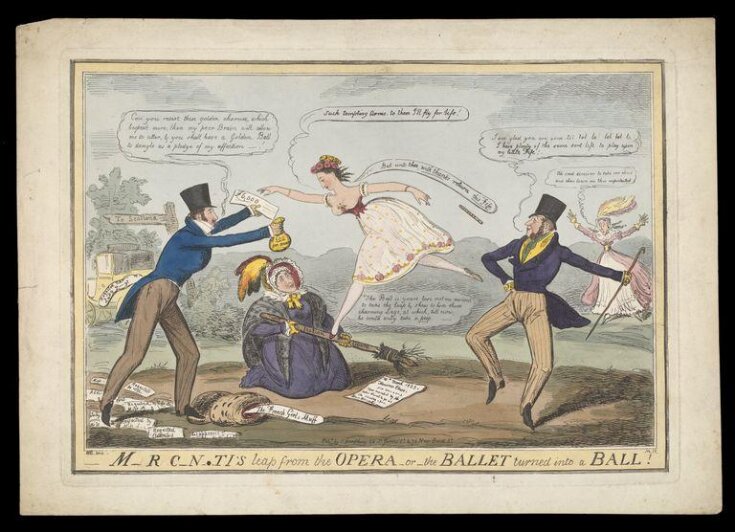

This print satirises the scandal that erupted in March 1823 when the celebrated 17-year old dancer Spanish dancer Maria Mercandotti married the noted dandy, gambler and hedonist Edwin Hughes Ball Hughes (1798-1863). Known in society as ‘Golden Ball’ due to his immense wealth, he was also a friend of the Prince Regent.

Mercandotti rose to fame at London’s King’s Theatre in 1822 when she was employed by the manager John Ebers to appear that season. When she first appeared in the corps de ballet of Pandore on the 19th January 1822 the reviewer in The Album noted her as: ‘another new luminary.. who has but just appeared above the horizon, but who promises long to shine – she is strikingly beautiful, and her countenance is strikingly expressive’. On 26th March the London public went wild for her when she starred in the title role of Cendrillon, the first ballet based on Perrault’s original Cinderella story. Dancing on point had been introduced to the London ballet in 1821, and the sylphlike Mercandotti perfectly suited the new dancing style as well as the silk tights and floating material of her costumes. One critic called her ‘A divine fairy sprite’ and she was besieged with suitors. A year later, on 8th March 1823, when she failed to appear as advertised in Daniel Auber’s ballet, Alfred, and a seemingly anxious Ebers appeared on stage to announce the disappearance of ‘The Andalucian Venus’ to the irate audience, she and Hughes Ball Hughes were leaving Leicester Square in a coach and four, along with Mercandotti’s mother. They travelled to Scotland where they married on Sunday 22nd March at Duff House, Banff, near Aberdeen, the home of the Earl of Fife who gave her away and who was widely rumoured to be her father. It became one of the great scandals of the age, and the assistance of Ebers in the affair was confirmed by his attendance at the wedding as a witness.

This satire shows Mercandotti eagerly jumping the Italian Opera House broom – a reference to a marriage ceremony that was not legally binding – towards the figure of her lover who stands proffering cash. Letters of rejection from Mercandotti to other suitors are strewn on the ground, while she is throwing away her metaphorical fife to John Ebers. Behind him stands the distraught figure of Hughes Ball Hughes’ previous lover while the carriage awaits on the other side of the image, by a signpost to Scotland. The marriage was not to last and they divorced in 1839.

Mercandotti rose to fame at London’s King’s Theatre in 1822 when she was employed by the manager John Ebers to appear that season. When she first appeared in the corps de ballet of Pandore on the 19th January 1822 the reviewer in The Album noted her as: ‘another new luminary.. who has but just appeared above the horizon, but who promises long to shine – she is strikingly beautiful, and her countenance is strikingly expressive’. On 26th March the London public went wild for her when she starred in the title role of Cendrillon, the first ballet based on Perrault’s original Cinderella story. Dancing on point had been introduced to the London ballet in 1821, and the sylphlike Mercandotti perfectly suited the new dancing style as well as the silk tights and floating material of her costumes. One critic called her ‘A divine fairy sprite’ and she was besieged with suitors. A year later, on 8th March 1823, when she failed to appear as advertised in Daniel Auber’s ballet, Alfred, and a seemingly anxious Ebers appeared on stage to announce the disappearance of ‘The Andalucian Venus’ to the irate audience, she and Hughes Ball Hughes were leaving Leicester Square in a coach and four, along with Mercandotti’s mother. They travelled to Scotland where they married on Sunday 22nd March at Duff House, Banff, near Aberdeen, the home of the Earl of Fife who gave her away and who was widely rumoured to be her father. It became one of the great scandals of the age, and the assistance of Ebers in the affair was confirmed by his attendance at the wedding as a witness.

This satire shows Mercandotti eagerly jumping the Italian Opera House broom – a reference to a marriage ceremony that was not legally binding – towards the figure of her lover who stands proffering cash. Letters of rejection from Mercandotti to other suitors are strewn on the ground, while she is throwing away her metaphorical fife to John Ebers. Behind him stands the distraught figure of Hughes Ball Hughes’ previous lover while the carriage awaits on the other side of the image, by a signpost to Scotland. The marriage was not to last and they divorced in 1839.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | M_rcan_._ti's Leap from the Opera, or the Ballet Turned into a Ball (assigned by artist) |

| Materials and techniques | Hand coloured etching |

| Brief description | Print entitled '_M_rc_an.ti's leap from the opera, or, The ballet turned into a Ball', published by G. Humphrey, Harry Beard Collection. |

| Physical description | Print entitled '_M_rc_an.ti's leap from the opera, or, The ballet turned into a Ball', depicting Maria Mercandotti leaping into the arms of Edward Hughes Ball's arms as he holds out money and a cheque towards her. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Credit line | Harry R. Beard Collection, given by Isobel Beard |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | This print satirises the scandal that erupted in March 1823 when the celebrated 17-year old dancer Spanish dancer Maria Mercandotti married the noted dandy, gambler and hedonist Edwin Hughes Ball Hughes (1798-1863). Known in society as ‘Golden Ball’ due to his immense wealth, he was also a friend of the Prince Regent. Mercandotti rose to fame at London’s King’s Theatre in 1822 when she was employed by the manager John Ebers to appear that season. When she first appeared in the corps de ballet of Pandore on the 19th January 1822 the reviewer in The Album noted her as: ‘another new luminary.. who has but just appeared above the horizon, but who promises long to shine – she is strikingly beautiful, and her countenance is strikingly expressive’. On 26th March the London public went wild for her when she starred in the title role of Cendrillon, the first ballet based on Perrault’s original Cinderella story. Dancing on point had been introduced to the London ballet in 1821, and the sylphlike Mercandotti perfectly suited the new dancing style as well as the silk tights and floating material of her costumes. One critic called her ‘A divine fairy sprite’ and she was besieged with suitors. A year later, on 8th March 1823, when she failed to appear as advertised in Daniel Auber’s ballet, Alfred, and a seemingly anxious Ebers appeared on stage to announce the disappearance of ‘The Andalucian Venus’ to the irate audience, she and Hughes Ball Hughes were leaving Leicester Square in a coach and four, along with Mercandotti’s mother. They travelled to Scotland where they married on Sunday 22nd March at Duff House, Banff, near Aberdeen, the home of the Earl of Fife who gave her away and who was widely rumoured to be her father. It became one of the great scandals of the age, and the assistance of Ebers in the affair was confirmed by his attendance at the wedding as a witness. This satire shows Mercandotti eagerly jumping the Italian Opera House broom – a reference to a marriage ceremony that was not legally binding – towards the figure of her lover who stands proffering cash. Letters of rejection from Mercandotti to other suitors are strewn on the ground, while she is throwing away her metaphorical fife to John Ebers. Behind him stands the distraught figure of Hughes Ball Hughes’ previous lover while the carriage awaits on the other side of the image, by a signpost to Scotland. The marriage was not to last and they divorced in 1839. |

| Associated objects |

|

| Other number | F.121-17 - H Beard collection numbering |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | S.2567-2009 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | September 22, 2009 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSON