Miss Miles' House

Dolls' House

1890 (made)

1890 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

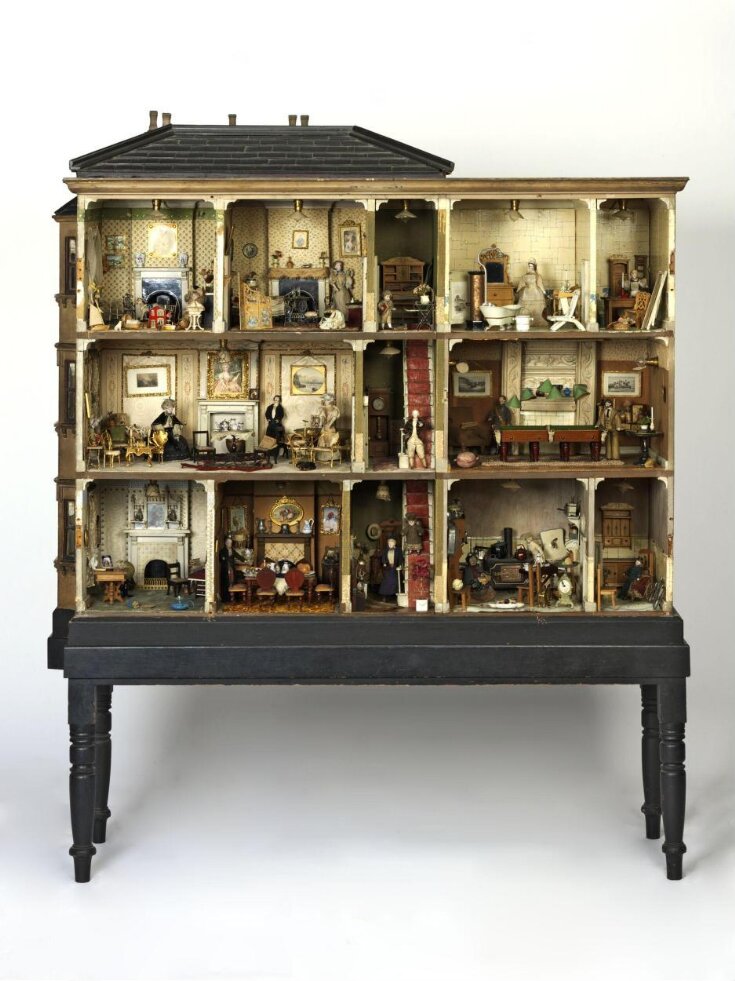

Made by Amy Miles when she was in her thirties, this evocative dolls’ house looks back to her childhood and the house where she grew up in Friern Barnet, North London. It was one of the first dolls’ houses to be collected by the V&A, and has been central to the collection ever since.

Rather than creating a snapshot of a particular time, Amy Miles included gadgets and inventions popular from the 1850s onwards. The geyser in the bathroom was patented in 1868, but was soon surpassed my more reliable methods of heating water. The telephone in the hall would have appeared after 1876 and domestic electric lights weren’t available until the 1890s. In the dining room sits a tiered white wedding cake - made of real sponge cake and icing. These first appeared at the wedding of Victoria’s son, Prince Leopold, in 1882.

Amy Miles (1857 – 1928) grew up in a prosperous Victorian household, overseen by her father, John Miles, who was manager of a book publishers, investor in the New River Company, and active philanthropist. Amy was the youngest of five children, and all the girls were taught at home by governesses.

Rather than creating a snapshot of a particular time, Amy Miles included gadgets and inventions popular from the 1850s onwards. The geyser in the bathroom was patented in 1868, but was soon surpassed my more reliable methods of heating water. The telephone in the hall would have appeared after 1876 and domestic electric lights weren’t available until the 1890s. In the dining room sits a tiered white wedding cake - made of real sponge cake and icing. These first appeared at the wedding of Victoria’s son, Prince Leopold, in 1882.

Amy Miles (1857 – 1928) grew up in a prosperous Victorian household, overseen by her father, John Miles, who was manager of a book publishers, investor in the New River Company, and active philanthropist. Amy was the youngest of five children, and all the girls were taught at home by governesses.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Miss Miles' House (popular title) |

| Materials and techniques | Wood |

| Brief description | Dolls' house known as Miss Miles House made in England in 1890 |

| Physical description | The house is a large structure consisting of ten rooms. It originally had an artist's studio in the roof. On the ground level is a child's schoolroom, a small dining room, a kitchen and a pantry. On the next level is a large and elegant drawing room and a recreation room with a large billiard table. The top floor has a nursery, a bedroom, a bathroom and a utility room. A staircase runs through the centre of the house. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Production type | Unique |

| Credit line | Given by Miss Amy Miles |

| Object history | Miss Amy Miles brought photographs of her dolls’ house to the V&A in South Kensington in August 1915. She met with Oliver Bracket, curator of furniture, who considered it to be “a remarkable curiosity. In view of the proposal to form a room of exhibits to interest children… we should accept the loan”. The display was set up for Christmas 1915 and Amy herself came to arrange the furniture in the dolls’ house. In May 1918, as the First World War dragged on, the dolls’ house remained in the museum. A letter was sent to Amy Miles: “In view of the possible increase of risk from attack by hostile aircraft, we have been considering new measures to be taken for the protection of the treasures exhibited in this Museum, including the dolls’ house”. She responded “I really am very anxious to get it back again but I had to wait and see what the management would arrange… I have plenty of room for it here and am longing to have it back.” News of the dolls’ house next arrived in 1921, when Rev Henry Miles wrote offering it as a gift. “My sister”, he wrote, “is now non-compos mentis… and I have to manage her estate. She has directed in her will that the dolls’ house is to be offered to you for the museum”. The house was accepted for the new Children’s Section being planned at Bethnal Green Museum (now the V&A Museum of Childhood), and was one of the very first exhibits for this innovative venture. |

| Historical context | This dolls’ house is an evocative and personal late Victorian home. Made by Amy Miles when she was in her thirties and forties, it looks back to her childhood and the house she grew up in. It was one of the first dolls’ houses to be acquired by the V&A Museum, and has been central to the collection ever since. “The wonderful dolls’ house caused many shrill cries of delight during the short time that the children’s room was open. Its electric light in every room, its artist studio in the garret, its playroom with toys for the toy children who lived there, its butler with his champagne on ice, its billiard room with a wonderful table, its bathroom with a geyser, its endless new joys that eager little eyes could ferret out and scream the discovery to a small sister or brother, made it the crowning glory of the room.” – Newspaper article ‘Farewell to the Dolls’, January 1916 “It seems to me that Miss Miles’s Dolls House can hardly be regarded as giving a true idea of a home of any period” – Oliver Brackett, Curator of Furniture, V&A Museum, 1921 It is tempting to interpret the character of the owner from the furnishing of a dolls’ house. With Amy Miles, this is even more beguiling as the details seem so realistic, so domestic. However, as Mr. Brackett asserted in the 1920s, this dolls’ house isn’t a snap shot of any time; there are contradictions and anachronisms throughout the many rooms. The furnishings of Amy Miles’ dolls’ house include gadgets and inventions popular from the 1850s onwards. The co-existence in the house of a hot water geyser (invented 1868 and replaced quite soon after by up-to-date models) and electric lights (available in homes from 1890s) shows how the house spans Amy Miles’ lifetime, accumulating technology from different decades. Amy brought photographs of her dolls’ house to the V&A in South Kensington in August 1915. She met with Oliver Bracket, curator of furniture, who considered it to be “a remarkable curiosity. In view of the proposal to form a room of exhibits to interest children… we should accept the loan”. The display was set up for Christmas 1915 and Amy Miles herself came to arrange the furniture in the dolls’ house. In May 1918, as the First World War dragged on, the dolls’ house remained in the museum. A letter was sent to Amy Miles: “In view of the possible increase of risk from attack by hostile aircraft, we have been considering new measures to be taken for the protection of the treasures exhibited in this Museum, including the dolls’ house”. She responded “I really am very anxious to get it back again but I had to wait and see what the management would arrange… I have plenty of room for it here and am longing to have it back.” News of the dolls’ house next arrived in 1921, when Rev Henry Miles wrote offering it as a gift. “My sister”, he wrote, “is now non-compos mentis… and I have to manage her estate. She has directed in her will that the dolls’ house is to be offered to you for the museum”. The house was accepted for the new Children’s Section being planned at Bethnal Green Museum (now the V&A Museum of Childhood), and was one of the very first exhibits for this innovative venture. Amy Miles Amy Caroline Miles was the youngest of five surviving children of John and Sophie Miles. She was born in 1857, in Friern Barnet, then still a village north of London. Her family lived in the Manor House, a name given to any large imposing residence in the nineteenth century. An old house had stood there for several centuries, but when John Miles bought the house and land in about 1851, this was demolished and a new family home built in its place. In 1861, when Amy was 4, the large household comprised fifteen people, including eight live-in servants. A gardener and his family lived close by. The children had three servants allocated to their care: a governess, Jamima Murray, a nurse, Louisa Rudland, and a nurserymaid, Eliza Bennett. Louisa Rudland stayed with the Miles family for nearly 30 years, long after the children were grown up. Only shortly before her death in 1890 did she retire and move to a small house nearby. In 1871, the year that education became compulsory for all, 14 year old Amy and her 17 year old sister Eliza were being taught by Fiander Heathcoate, a live-in governess in her 30s who had been born in Yorkshire. “The Manor House”, stated the local newspaper in 1902, “is a spacious and substantial family residence, containing on the two upper floors 12 bedrooms, 2 dressing-rooms, and bathroom; on the ground floor, dining room, drawing room, library, entrance hall, and complete offices. Matured pleasure grounds, ornamented with fine old timber and various shrubs.” This was a privileged upbringing, with material comforts which Amy perhaps sought to suggest in the furnishing of her dolls’ house. The toy children have a nursery at the top of the house, and a schoolroom with a bay window looking over the imaginary garden. John Miles (1816 – 1886) As a wealthy Victorian man with fingers in many pies, the records of John Miles’s life are more conventional. Company records, census returns, news reports and architecture memorialise his role in the wider social and business community of his time. Born into a dissenting family in 1813, John was already a widower when he married Sophia Hodgson on 1st February 1846. They had five children: Sophia (born 1848), Charles (1849), Henry (1851), Eliza (1854), Amy (1857), and Ellen (1859). All except Ellen survived childhood. John Miles was a Bookseller and Publisher, registered with the Stationers’ Company as head of the firm Simpkin, Marshall & Co., Wholesale Booksellers. At the time this company was publishing Maria Edgworth, John Gay and religious instruction books, school books and political pamphlets. He donated the stock for a lending library St James’ church, Friern Barnet. John Miles also had financial interests elsewhere. He was a Governor of the New River Company,1 which oversaw the provision of clean water to the centre of London. His interest in this role inspired the name of Myddleton Park, which joined John Miles’ house to the church. Sir Joseph Myddleton was the Elizabethan entrepreneur who established the New River. [i] A transcript of the registers of the company of stationers of London (v. 5) (London : Birmingham : Priv. Print., 1875-77 ; 1894.) Friern Barnet was shaped by John Miles’ active philanthropy. In 1855, he gave £100 for the upkeep of the almshouses; in 1859 he provided the land for an infants’ school next to St James’ church. His largest project was the building of a whole new church, All Saints, which was finished in 1881. Second son Henry became vicar of the new church. Though local legend records he wasn’t immediately keen, since as a child “he had upset local land-owners riding rough-shod over their fields… but he agreed, moved with his newly wed bride into the Vicarage, and stayed very happily for 50 years”.2 Around this time, several rooms in the Manor House were photographed. In these photos we can see the plush furnishings of the house which may have inspired the dolls’ house. Eerily empty, the cluttered but cosy rooms do seem familiar. A three-legged table in one corner has a replica in miniature, and Amy repeated the arrangement of pictures on the wall. John Miles died in 1886, leaving a fortune of £53,000 plus stocks and property. In 1907, the Manor House and the undeveloped estate was sold, to become North Middlesex Golf Club. Amy Miles’ childhood home is still there, now the clubhouse. But to imagine what life was like for Amy as a child, we must look back to the dolls’ house. |

| Summary | Made by Amy Miles when she was in her thirties, this evocative dolls’ house looks back to her childhood and the house where she grew up in Friern Barnet, North London. It was one of the first dolls’ houses to be collected by the V&A, and has been central to the collection ever since. Rather than creating a snapshot of a particular time, Amy Miles included gadgets and inventions popular from the 1850s onwards. The geyser in the bathroom was patented in 1868, but was soon surpassed my more reliable methods of heating water. The telephone in the hall would have appeared after 1876 and domestic electric lights weren’t available until the 1890s. In the dining room sits a tiered white wedding cake - made of real sponge cake and icing. These first appeared at the wedding of Victoria’s son, Prince Leopold, in 1882. Amy Miles (1857 – 1928) grew up in a prosperous Victorian household, overseen by her father, John Miles, who was manager of a book publishers, investor in the New River Company, and active philanthropist. Amy was the youngest of five children, and all the girls were taught at home by governesses. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | W.146-1921 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | May 23, 2005 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest