| Categories | |

| Object type | |

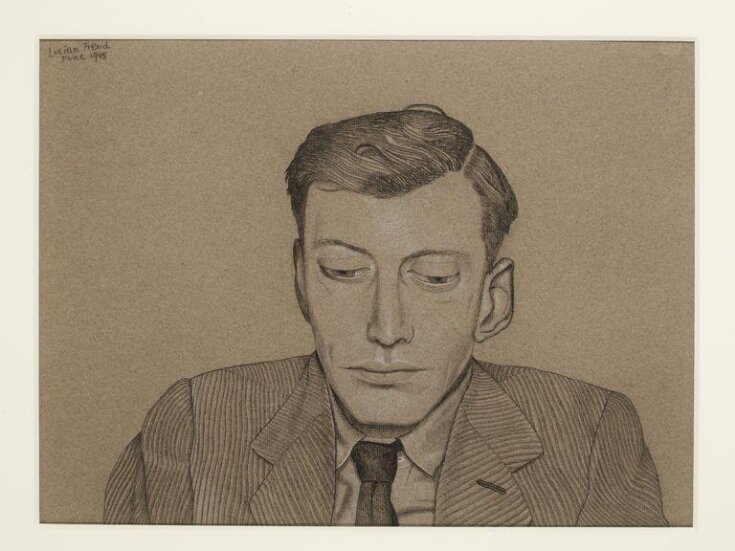

| Title | Portrait of Peter Watson |

| Materials and techniques | Charcoal and white chalk on grey-brown paper |

| Brief description | Freud, Lucian; portrait of Peter Watson, 1945; charcoal and white chalk on grey-brown paper |

| Dimensions | - Height: 36cm

- Width: 48.1cm

- Oak frame height: 525mm

- Oak frame width: 627mm

- Oak frame depth: 32mm

- Height: 13.25in

(Note: Taken from Departmental Circulation Register 1958)

- Width: 17.5in

(Note: Taken from Departmental Circulation Register 1958)

|

| Marks and inscriptions | Signed and dated 'Lucian Freud June 1945'

|

| Object history | Formerly in the collection of the late Peter Watson.

Bought from Hanover Gallery, 30 Oct 1958. |

| Subject depicted | |

| Summary | During the 1940s Lucian Freud concentrated on drawing, and in particular used it for portraiture: this portrait represents his friend Peter Watson, the patron, collector and proprietor of Horizon magazine. The quality of draughtsmanship coupled with the sense of unease communicated in this drawing bears out the aptness of critic Herbert Read’s description of Freud as ‘the Ingres of existentialism’. |

| Bibliographic references | - Owens, Susan, The Art of Drawing British Masters and Methods since 1600, V&A Publishing, London, 2013, p. 162, fig. 130

- Lucian Freud Drawings London: Blian Southern, 2012. ISBN: 978-0-9569904-3-3.

- Taken from Departmental Circulation Register 1958

- Macfarlane, Kate (Editor) Close: drawn portraits London: Drawing Room, 2019

Lucian Freud had little formal art training and developed his own style of drawing which was based on the close study of his subject. He was introduced to Peter Watson, an English art collector and benefactor, by Stephen Spender in 1939. He made this portrait during an intense period of drawing and it displays a marked change in style from his naïve portrait of Watson in oil in 1941. Freud’s interest in Albrecht Dürer at this time encouraged his linear precision which records virtually every hair and corduroy stripe: ‘… I was fascinated by hair. I thought of it like fur on people.’ The sensory organs – eyes, mouth and ears – are all enlarged, an indicator of Freud’s interest in the senses. ‘…I sometimes looked so hard at a subject that they would undergo an involuntary magnification’. He described his working process in the period he made this drawing:

In those days I didn’t work over the whole image and bring up the parts together, as I tend to do now. I would work in a part until I got it how I thought it should be and then move to another part. I didn’t go over the same area very often. I did it until I got it right.

Freud said that he draws and paints people in order to get to know them. Here his proximity to his subject is obvious and seems to be forcing Watson to look down to alleviate discomfort.

I was visually aggressive. I would sit very close and stare. It could be uncomfortable for both of us. I was afraid that if I didn’t pay very strict attention to every one of the things that attracted my eye the whole painting would fall apart. I was learning to see and I didn’t want to be lazy about it.

Watson’s pose is almost identical to that adopted by Livingstone in Hockney’s portrait but the two works express very different forms of observation and closeness.

I never put anything into a picture that I don’t actually see … However, I’m not trying to make a copy of the person. I’m trying to relay something of who they are as a physical and emotional presence … [If you] focus on their physical presence, interesting things happen. You find that you capture something about them neither of you knew.

Watson’s biographers noted that this drawing invoked his ‘melancholy beauty’.

- Kate Macafarlane

- Dronfield, J. and Clark, A., 2015. Queer Saint: The Cultured Life of Peter Watson.

"Elegant, charming and hungrily sexual, Peter Watson had a taste for edgy, disreputable lovers. Gore Vidal described him as ‘a charming man, tall, thin, perverse. One of those intricate English queer types who usually end up as field marshals’. Watson was the unrequited love of Cecil Beaton’s life – his ‘queer saint’ – but Watson preferred the risk associated with younger and less sophisticated lovers.

Peter Watson fuelled the engine of mid-20th century art, using his enormous wealth to support artists such as Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, John Craxton, Paul Klee, Picasso, Dali, Giacometti and many others, and was painted by several of them."

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | |