Coffer

about 1600 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

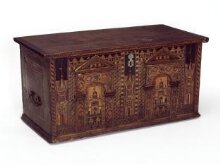

This type of chest is characterised by its construction using dovetailed boards and decoration of geometrical and architectural designs in marquetry and inlay. In many respects they resemble chests made in Germany, and are now thought to have been made in London, particularly Southwark, by immigrants from northern Germany and the Netherlands from about 1560. Their decoration of picturesque towered buildings probably derive from 16th-century printed designs, such as those published by Hans Vredeman de Vries (1527-1604). During the twentieth century they came to be known as ’Nonsuch’ chests, after Henry VIII’s palace of Nonsuch in Surrey, because their decoration of fanciful buildings was thought, wrongly, to represent that building.

This example was said to have come from a ‘mansion’ in Buckinghamshire. Much of the glued surface decoration was restored after it came to the Museum. When new the marquetry decoration in various colours would have been much brighter.

This example was said to have come from a ‘mansion’ in Buckinghamshire. Much of the glued surface decoration was restored after it came to the Museum. When new the marquetry decoration in various colours would have been much brighter.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Oak, with inlay of various woods and metal fittings |

| Brief description | Lidded chest, oak with inlay, English, c. 1600 |

| Physical description | Lidded chest decorated on its front, lid and ends with geometrical inlay and marquetry. Chest constructed of oak boards, the ends dovetailed to the front and back and the bottom nailed up, with applied mouldings around the base. The back formed by three horizontally grained planks, with irregular scrub plane marks. The lid formed of three planks with a cleat at either end, held on two tinned iron internal strap hinges, and with a internal lock hasp which corresponds to an internal lock and external escutcheon; with a wrought iron handle fitted to each end. There is a key to the lock. The decoration of the chest front consists of two symmetrical marquetry panels depicting a tall building with cupola, each of which is set within a pedimented arch formed by applied mouldings with geometrical inlay, and geometrical inlay borders. At the two ends of the front, flanking the two panels, and between them are three inlaid towers. An alternating vertical band of marquetry runs up the outermost edges of the front. Both ends are inlayed with a square border of two colours. Along the front edge of the lid, is a double marquetry band of alternating squares. The similar Lady Lever chest is described (The Lady Lever Art Gallery (1996), p. 44 as being of Oak inlaid with rosewood, maple, box(?), and green-stained holly or sycamore. The similar Temple Newsam chest on stand c.1600 (TEMPLE NEWSAM: Christopher Gilbert: Furniture at Temple Newsam House and Lotherton Hall. Vols. I, (London, 1978), no. 144 is described as 'Oak, with lime tills, drawer linings and river corner blocks; the intarsia executed in ebonized and natural oak, light and stained woods.' |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Object history | Bought for £10 from Messrs. Wagstaff and Clare, London Road, Newport Pagnell, Bucks,(RP 81311/1905, 1337/1905), 'very badly damaged and many portions missing'. The vendor wrote to the Museum (Jan 24 1905) offering the chest 'just bought at a mansion in the district...in the same condition as we received it not restored in any way'. A photograph of the chest "just prior to arrival at the Museum" shows the marquetry front with some losses, particulary along the lower 6-8". Sections of the applied arches are missing, and the moulding along the left (proper right) end (the right end is not visible in the photograph). A V&A photograph (neg. 54804, taken in 1925) shows the chest substantially restored. 'Restored in 1964 and cleaned in V&A furniture conservation 1967. The name Nonsuch or Nonesuch is given to early inlaid chests of this type in which the design of the inlay is architectural in character and represents a quaint building with castellations, high-pitched roofs, cupolas and steeples set with vanes, and flying flags. Nonsuch or Nonesuch Palace, at Ewell, in Surrey, was so called as being without equal. It attained great popularity, and the term Nonsuch was applied to such things as 'Nonsuch apples,' 'Nonsuch lotteries,' 'Nonsuch chests.' The palace was built by Henry VIII, and was given by Charles II to Lady Castlemaine, whom he created Baroness Nonsuch, and by her it was finally pulled down. (For account of Nonsuch see Blomfield, R., 'Renaissance Architecture in England,' pp. 16-18; Gotch, J. A., 'Early Renaissance Architecture in England,' pp. 35-36; 'Nonsuch and Theobalds,' by H. C. Andrews, in 'Architectural Review,' Vol. XXXVII, p. 59, and Vol. XXXIX, p. 56, 1915-16.) It is also suggested that the source from which this peculiar decoration on these chests came was Nonsuch House on London Bridge (see Roe, F., 'The Connoisseur,' Vol. LVIII, p. 205, 1920). But there is no reason to suppose that either of the two buildings entitled Nonesuch are represented, rather than any other typical Tudor or Elizabethan house, conventionalized for purpose of design. Inlaid woodwork of this type is now thought to have been made in London, particularly Southwark, by immigrants from northern Germany and the Netherlands from about 1580. Research has noted similarities between this type of decoration and examples made in Germany, particularly near Cologne, at about this time. These pieces were often decorated with archtitectural fantasies, inspired by published collections of engravings such as Variae archiecturae formae published by Hans Vredeman de Vries (1527-1604), rather than Nonsuch Palace. The sources were probably modified and simplified (necessarily, in being translated into marquetry and inlay), in workshop drawings into the fairly generic buildings we see. That creative process of selection and adaptation makes it very difficult to identify a single clear source. Whole runs of inlay were probably made by independent specialists, and could be applied to oak chests, made separately by a joiner. As Edmund Maria Bolton tells us in Elements of Armories (1610): 'At St. Olaves in Southwark, you shall learn, among the joyenrs what Inlayes and Marquetrie meane. Inlaye ... is a laying of colour'd wood in their Wainscot works, Bedsteads, Cupbords, Chayres and the like'. |

| Historical context | Thorpe notes a reference 'in the dispositions of a North-country merchant who knew the Danske business' (1588) to "One large Danke chist with insett worke"; and another to "Item a Danske cabonett inlaid with coloured wood the forefront three stories of colombes V li' (1614), which he takes to indicate that they were products of the Baltic trade centred on Gdansk (Dantzig), not Denmark (also known as Danske), with the English east and south coast ports. He suggests that they may have been made by Mennonite craftsmen who had fled religious persection in the Netherlands. Thorpe notes that Percy Macquoid, whose chest of this type, dated 1592 (History of English furniture, Vol. I, Age of Oak, 1904, plate VIII b.) is now in the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight (inv. no. LL 4723 (L 6)), related the marquetry designs to a drawing of the Palace of Nonsuch, Ewell (Surrey) by Joris Hoefnagel I, dated 1568 (used for an engraving of 1582), and the engraving of Nonsuch in Paul Hentzner's account of his travels 'Itinerarium Germaniae Angliae Italiae (Nuremberg 1612), but that the comparision is unconvincing. Forman suggests that the towered buildings depicted on this type of chest may be a debased representation of Cologne Cathedral, depicted in greater detail on German chests of the same period. Chinnery (p. 355) suggests that 'attempts actually to identify a specimen of a Danske chest have failed, since we can only conjecture as to exactly what they were like, despite their very common mentions in inventories.' He thinks that Danske chests were of some softwood, not oak which were often distinguished from Danske as 'wainscot'. He suggests (p. 356) that chests of this type were imported to England from Cologne and the Rhineland via Antwerp and the Rhine Estuary, and may therefore be what English inventories refer to as 'Flanders' chests. W.A.Thorpe, Spruce and Danske: The origins of Baltic Chests (Country Life Annual, 1951, pp. 152-62. Peter Thornton, Furniture History, 1971, pp. 66-9 Benno Forman, Continental furniture craftsmen in London: 1511-1625 (Furniture History VII, 1971) Victor Chinnery, Oak Furniture. The British Tradtion (Woodbridge, 1979), fig. 3:358 |

| Summary | This type of chest is characterised by its construction using dovetailed boards and decoration of geometrical and architectural designs in marquetry and inlay. In many respects they resemble chests made in Germany, and are now thought to have been made in London, particularly Southwark, by immigrants from northern Germany and the Netherlands from about 1560. Their decoration of picturesque towered buildings probably derive from 16th-century printed designs, such as those published by Hans Vredeman de Vries (1527-1604). During the twentieth century they came to be known as ’Nonsuch’ chests, after Henry VIII’s palace of Nonsuch in Surrey, because their decoration of fanciful buildings was thought, wrongly, to represent that building. This example was said to have come from a ‘mansion’ in Buckinghamshire. Much of the glued surface decoration was restored after it came to the Museum. When new the marquetry decoration in various colours would have been much brighter. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 342:1, 2-1905 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 16, 2005 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest