The Rolls Plaques

Plaque

ca. 1160 (made)

ca. 1160 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

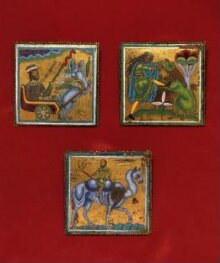

This is one of a group known as the Llangattock or Rolls Plaques which is of outstanding interest both technically and iconographically.

It is a brilliant example of the art of enamelling as practised in the 12th century in the area around the Meuse (now in Belgium), centred on the bishopric of Liège. The boldly engraved figures are enriched by a subtle range of enamel colours, often blended to emphasise figure contours or drapery folds. Prominent features such as heads and hands are not enamelled but engraved and gilded. Mosan enamellers were amongst the most skilled craftsmen of their time, and produced items for liturgical use – crosses, altars, reliquaries and candlesticks – numbers of which survive.

This plaque depicts Alexander the Great in a chariot.

It is a brilliant example of the art of enamelling as practised in the 12th century in the area around the Meuse (now in Belgium), centred on the bishopric of Liège. The boldly engraved figures are enriched by a subtle range of enamel colours, often blended to emphasise figure contours or drapery folds. Prominent features such as heads and hands are not enamelled but engraved and gilded. Mosan enamellers were amongst the most skilled craftsmen of their time, and produced items for liturgical use – crosses, altars, reliquaries and candlesticks – numbers of which survive.

This plaque depicts Alexander the Great in a chariot.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Titles |

|

| Materials and techniques | Copper alloy, engraved; gold; enamel |

| Brief description | Plaque of copper gilt and enamelled in champleve. |

| Physical description | Square plaque of copper alloy, engraved, gilded and enamelled, depicting the Ascension of King Alexander to the Heavens in a chariot drawn by griffins. Alexander's Celestial Journey (for the literary sources and iconography of this scene, see most recently Schmidt 1988). Back: Coated with brown varnish (not original) ; no other features. Front: The enamel frame is of turquoise within off-white. The celestial regions of the legend are represented at the top left and right by undulating bands of pale turquoise/mid-green/yellow, and of deep blue/pale blue/blue white, as well as a field of deep translucent red at top left. Alexander (ALEXANDER in blue enamel is inscribed diagonally next to his sceptre) is seated in three-quarters profile in a chariot of deep translucent red/ opaque red, yellow, deep blue/pale blue, its wheel of mid-green with turquoise spokes and a white hub, its shaft of opaque red. The king is magnificently dressed; his tunic is of deep blue and over its surface a pattern of circles enclosing small quatrefoils is reserved in the gilded metal, while his cuffs are a mid-green studded with red dots and his collar has the same coloured pattern as the cuffs but with flecks of white. His tiara has a white circlet topped by two semicircles of turquoise and opaque red, which are framed by two tiny white 'pearls', with a third yellow 'pearl' in the centre. He holds a deep green sceptre and the meat of the legend, which lures the starving gryphons towards the celestial regions, is shown entwined in opaque red around its top. The gryphons themselves are shown ascending towards the right; each is treated with a different combination of glasses both on its body and its wings, but these combinations are, for the most part, the now-familiar ones found throughout the group (turquoise/white, pale blue/blue white, pale green/white, mid-green/yellow, deep blue/mid-green). However the further wing of the nearest gryphon is given a most unusual treatment with opaque red/yellow/turquoise, creating a dappled effect. Deep translucent red is used at the base of one of the wings and for the eye pupils of the beasts, whereas the main areas of the eyes are of opaque red. It is possible, though not certain, that the outline of eyes and eye pupils are delineated with cloisonné cell-work; verification of this is difficult, because of corrosion of the copper in this area. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Production type | Unique |

| Credit line | Purchased with the assistance of the National Heritage Memorial Fund and Art Fund |

| Object history | The plaques were first publicly exhibited in 1857 at the Manchester Art Treasures exhibition, and again in 1862 at the South Kensington Museum Loan Exhibitions by J.E.W. Rolls (cat. p.83, nos.115-7). They were first discussed at length by H.P. Mitchell (of the Metalwork Dept., V&A) in two influential articles in the Burlington Magazine, 1919 (vol. XXXV, pp.34 ff. and 217 ff.): he associated them on grounds of style and technique with two plaques in the Louvre. Subsequent discussion has focussed on the iconographic interpretation of these and other plaques -the series being now extended to twelve, all with similar borders, attachment holes and styles. An exceptional feature of the Rolls plaques is that their iconography is not overtly Biblical unlike most of the rest of the series. Of the plaques -Alexander's ascent to the Heavens and the man on a camel- treat subjects not otherwise recorded in enamel, and illustrate a secular side of life which has rarely survived. The Alexander scene derives from medieval romance, the other is unknown. However, they could also bear moral or theological interpretations (Alexander representing pride, Christ's Ascension, the man on a camel as Christ's humility, and Samson and the lion as a prefiguration of the Harrowing of Hell). The entire series probably showed the complete Life of Christ, with Old Testament prefigurations, and probably formed an altarpiece. It has even been suggested that the plaques were for Abbot Suger's great altar cross at St. Denis (although this seems unlikely, since his cross was probably decorated only with Christ's Passion and Resurrection). Another plaque from this group -Moses and the brazen serpent (Numbers, XXI,9) -is in the Museum (M.59-1952) but this is very badly damaged and lacks all enamel. Others from the series are now in the British Museum (Naman bathing in the Jordan); New York, Metropolitan Museum (the Baptism, the Crucifixion, the Holy Women at the Tomb, Pentecost); Paris, Louvre (Sts. Sebastian, Tranquillinus, and Livinus). Various writers have drawn attention to the close stylistic parallels between the series of plaques and the great Stavelot reliquary-triptych (now in the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York). This was probably commissioned for his abbey at Stavelot by Abbot Wibald, diplomat, politician and counsellor to the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa. |

| Historical context | THE ROLLS PLAQUES Three plaques, perhaps from an altarpiece or shrine, Mosan, c.1150-70 Copper gilt with champlevé and some details in cloisonné. The scenes depicted are: (a) a man on a camel (b) Samson and the lion (c) the Ascension of King Alexander to the Heavens. The three plaques are of outstanding interest both technically and iconographically. They are brilliant examples of the art of enamelling as practised in the twelfth century in the area around the Meuse (now in Belgium), centred on the bishopric of Liège. The boldly engraved figures are enriched by a subtle range of enamel colours, often blended to emphasise figure contours or drapery folds. Prominent features such as heads and hands are not enamelled but engraved and gilded. Mosan enamellers were amongst the most skilled craftsmen of their time, and produced items for liturgical use - crosses, altars, reliquaries and candlesticks - numbers of which survive. At least two of the Rolls plaques appear, most unusually, to be secular in subject, one derived from the medieval Romance of Alexander. In this Alexander the Great explores the sky in a chariot pulled by griffins lured upwards by a baited pole. The meaning of this subject depended on its context and it could variously symbolise pride or faith. As with many medieval works, nothing is known of the identity of their artist, what object they adorned, or who commissioned them. Similar plaques, possibly from the same group, have been identified at the British Museum (Namaan bathing in the Jordan); New York, Metropolitan Museum (the Baptism, the Crucifixion, the Holy Women at the Tomb, Pentecost); Paris, the Louvre (a Centaur with a bow and arrow, a youth killing a dragon and Saints Sebastian, Tranquillinus and Livinus). The Rolls plaques, like those in the Louvre, are unusual in their inclusion of seemingly secular imagery. It is likely that the group formed part of a larger scheme - such as a large altar-piece - which might have combined religious subjects alongside secular scenes, which would have carried allegorical significance. Although it has been suggested that the plaques formed part of Abbot Suger’s famous enamelled altar cross, this seems unlikely as the decoration of the cross probably focused upon Christ’s Passion and Resurrection. The plaques are stylistically and technically very close indeed to a semi-circular enamel now in the British Museum, which shows Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester (d.1171) holding an altar. It seems possible that all the plaques originally adorned one of his gifts to his cathedral at Winchester, perhaps a great altar-piece which would have been destroyed in the 16th century Dissolution upheavals. |

| Production | Belgium Reason For Production: Commission |

| Subject depicted | |

| Summary | This is one of a group known as the Llangattock or Rolls Plaques which is of outstanding interest both technically and iconographically. It is a brilliant example of the art of enamelling as practised in the 12th century in the area around the Meuse (now in Belgium), centred on the bishopric of Liège. The boldly engraved figures are enriched by a subtle range of enamel colours, often blended to emphasise figure contours or drapery folds. Prominent features such as heads and hands are not enamelled but engraved and gilded. Mosan enamellers were amongst the most skilled craftsmen of their time, and produced items for liturgical use – crosses, altars, reliquaries and candlesticks – numbers of which survive. This plaque depicts Alexander the Great in a chariot. |

| Associated objects | |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.53-1988 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | August 26, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest