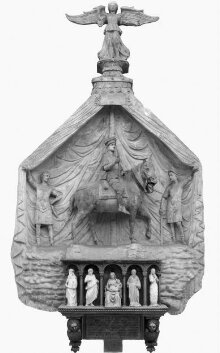

Monument to Marchese Spinetta Malaspina

Monument

ca. 1430-1435 (made)

ca. 1430-1435 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Spinetta Malaspina was a condottiere, or military commander, who died in 1352. His heirs later placed this memorial in the church that Spinetta founded outside the city. Its equestrian form is typical of Verona. Originally, the sculpture was probably brightly painted and gilded. The sarcophagus behind the row of figures is merely symbolic, indicating that the monument should be read as a cenotaph – a memorial with no body.

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 117 parts.

|

| Title | Monument to Marchese Spinetta Malaspina (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Stucco, marble, Istrian stone |

| Brief description | The monument of Marchese Spinetta Malaspina, attributed to Antonio da Firenze, with figures by Pietro di Niccolo Lamberti and Giovanni di Martino da Fiesole, Verona (Italy), about 1430-1435 |

| Physical description | Monument of Marchese Spinetta Malaspina, stucco, marble, Istrian stone |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions |

|

| Object history | The monument was purchased by J. P. Richter for six thousand francs (£240) in 1886. Documents in the museum archives describe its purchase and the problems that arose from its shipment to England. At the time, the monument was in a deconsecrated church that had been turned into a foundry. A descendent of Malaspina, who had rights over the church and the monument, sold both to Carolina Stanza, who then sold the monument to Richter. Though Richter was acting on behalf of the museum, he kept this hidden from the seller in order to keep the price down and to avoid any problems with the authorities. The museum had insisted that purchase only be approved depending on the ease and legality of the monument’s removal. According to Richter, it was only after the purchase went through that problems arose. The monument proved very difficult to disassemble. Unfortunately, when the disassembled monument arrived in London, the figures were found to be broken to pieces. The museum officials’ disappointment was added to when it was found that much of the monument was made of plaster and not terracotta, as Richter had described to them. Richter disputed this claim, though he had noted the same in an earlier letter. He also remarked that the problems in removal were due to the discovery that it was not terracotta, but cement mixed with brick and stonework with some plaster to join the parts. This proved much more difficult to remove, resulting in more damage and higher costs. The stone sarcophagus arrived in good condition though the cornice currently shows some damage. However, Richter admitted that he had to smuggle it out of Italy, because the Italian officials had “denied the permission of its exportation on account of the artistic and historic value of the monument.” The five statues in the niches of the sarcophagus were not part of the original purchase. At the time, the niches were empty and the statues were in the possession of the Marchese’s eponymous descendent. Richter, having recognized them from Litta’s engraving of the monument, purchased them for £100 and subsequently smuggled them out of the country. In 1887 the Italian government demanded that Richter produce a photograph of the sarcophagus as it was not to have been removed from the country. The authorities believed that he was keeping it in Florence. Richter noted that they were not asking about the whole monument, but only the sarcophagus, and that he had told the Italians that he was no longer the owner. In 1890 the Italian government sued Richter in order to get the monument back and/or have him fined. He lost the case, and had to pay a fine of 3,669 lire which was reimbursed to him by the Treasury. Historical significance: The monument originally was in the church of San Giovanni in Sacco, just outside the walls of Verona. Spinetta Malaspina founded the church, a nearby hospital and rest home to house six noblemen who had fallen on hard times. The church was destroyed in 1516 during the War of Cambrai. It was then knocked down in 1517. The rest home and a new church of the same name were rebuilt in 1519 inside the walls. The monument was transferred to the new church in 1536, as noted by the inscription in the small square below the tomb. (Dorini, 350; Pope-Hennessy, 368). Castellazzi did not mention the inscription, but stated that due to the destruction of the church by fire in 1516, the V&A monument was not the original monument erected by Spinetta's heirs, but was a reconstruction or imitation. However, she did not offer a date for its reconstruction. It is possible that the plaque refers to the reconstruction of the monument, and not to its movement from the old church to to the new. Franco has noted that the monument is one of only three that includes a cenotaph, equestrian figure and baldachino. (Franco, p.36-37). The inscription in the small rectangle that relates the movement of the monument from the church of San Giovanni in Sacco was there at least by the nineteenth century, as it is recorded in Penuti's engraving, though not in that published by dal Pozzo in the seventeenth century. The inscription in the large rectangle above it must have been added sometime after 1852, as it does not appear on any of the engravings of the monument published prior to its removal in 1886 by Richter. The same inscription is recorded by dal Pozzo and Orti Manara as in the church of San Giovanni in Sacco but they did not give an exact location. The five small statues in the niches of the cenotaph represent (from left to right) St. Jerome, St. John the Baptist and the Virgin and Child, a bearded male saint (perhaps St. Paul or St. Peter) and a figure who could be either the penitent Magdalene or St. Mary of Egpyt. Wolters noted their inclusion in Penuti’s engraving but disputed their original placement on the monument and that they dated to the first half of the 1400s, though he did not offer any alternatives. (Wolters, p.138, note 28) The sculptures differ on several points from those depicted in Penuti’s engraving. The Saint John the Baptist in the V&A monument has long hair, a belted hair-shirt and stands on a broken base. In the engraving, he has short hair, and has neither a belt nor a base. The others all have slightly different poses from the way the sculptures are depicted in the monument. However, the faces of the armed warriors and Spinetta Malaspina are also slightly different, and it is possible that the engraver took some artistic license. A seventeenth-century engraving of the monument also depicts the five sculptures differently; and shows a bald, bearded male saint in place of the St. John the Baptist. (dal Pozzo, p.406). Since it is not clear when the sculptures were removed, it is impossible to determine if the sculptures were accurately depicted in the engravings, or if the sculptures in the V&A monument were part of the original monument. The figure of Spinetta Malaspina and the two warriors holding the baldacchino share some similarities with figures in the terracotta reliefs created by Michele da Firenze (c.1404-36) for the chapel of the Pellegrini in the church of Sant’Anastasia in Verona in about 1433-38. In the relief of “The Way to Calvary,” Roman soldiers wear boots, hats, and skirts that are very similar to those worn by the warriors on the Malaspina monument. In the relief, an equestrian figure enters through an arch on the far right. He wears a similar hat and skirt to Spinetta Malatesta, and also carries a baton. The bridle and bit on the horse are also very similar. The extensive repair done to the Malaspina monument makes it difficult to determine the artist, and no documentation has survived. The awkwardness of the figures (especially the arms of the warriors) may also be due to repair. |

| Historical context | Equestrian monuments were typically part of monumental tombs for successful condottiere (military commanders for hire) or rulers. The format is Roman in origin and was used in the West to honour military leaders until the modern era. In Italy they could be painted or sculpted; and some of the more famous Renaissance examples include Paolo Uccello’s Sir John Hawkwood (1436) in the Florence cathedral, and Donatello’s Gattamelata (1447-50) outside the Santo in Padua. The use of the equestrian figure in funerary monuments in Verona dates to the tombs of the della Scala, the lords of Verona in the 1200s-1400s. Cangrande’s (1291-1329) tomb, erected by his son Mastino II (1308-1351) in 1308 was an early example of the genre in Italy. Mastino II’s tomb and that of Cansignorio (1340-1375) also included equestrian figures. Spinetta served as a condottiere under Can Grande della Scala, and acted as a witness to Mastino II’s marriage. Spinetta II, the nephew of the Marchese, ended the close ties with the della Scala family. Spinetta Malaspina’s monument is not a funerary monument but was intended to commemorate his role as condottiere and as the founder of the church. (Dorini, p.350, Pope-Hennessy, 368) This is evident from the inscription that was originally on the placard on the tree as shown in engravings in dal Pozzo, Orti Manara, and Litta.(dal Pozzo, facing p.406, Orti Manara, tav.ii, Litta, Malaspina section). The inscription once read M. SPINETAE FVNDATORI ANNO MCCCLII (M[archese] Spinetta founder [in the] year 1352). Dorini suggested that this is also corroborated Spinetta’s will, which included instructions for his burial. If he died in Verona or Vicenza, he was to be buried in San Giovanni in Sacco. If he died in Lunigiana in Tuscany, he was to be buried in Santa Margherita della Verruocola, near the family castle. Though he died in Lunigiania, there is no evidence of his tomb either there or in Verona (Dorini, p. 350-51). All scholars have noted the similarities between the V&A monument and the monument to Cortesia da Serego (Pope-Hennessy, Wolters, Franco). Serego was a fourteenth century condottiere also in the service of the della Scala family, whose descendents commissioned a commemorative monument in 1429 in the church of Santa’Anastasia in Verona, where it still is today. Both monuments have an equestrian figure standing above a cenotaph with five niches for sculptures, two warriors who standing on a rocky surface as they open a large baldachin surmounted by a standing figure – in the Serego monument an unidentified male warrior saint, and in the Malaspina monument an angel. Scholars have suggested that the Malaspina heirs copied the Serego in erecting the monument. The Serego monument was originally polychromed and has a frescoed background; it is likely that the Malaspina monument was polychromed though no evidence remains of frescoes. There is also no longer evidence of the inscriptions on the banderoles once held by the angel and to either side of the baldacchino, which are shown in engravings. The inscription held by the angel read: ME COMITE AD COELVM FOELICITER INDE VOLABVNT PER TE (Accompany me happily to the heavens where they will fly to you). The inscription on either side of the baldacchino read CORPORA SARCOPHAGO/PER TE TVMVLTA RESVRGENT (The body (in the) sarcophagus will rise (out of ) the tomb through you). The baldacchino was a motif popular in funerary monuments of the 1300s. It has been suggested that its use in the tomb monument of Filippo Guantieri (ca.1424-30), a Veronese who died in Florence, was deliberately archaicizing and meant to evoke the tomb of Giovanni della Scala (Wolters, 96); it is possible that a similar motivation was behind its use in the Serego monument or the Malaspina monument. |

| Production | Repaired 1536, Latin inscription probably added after 1852, damaged and heavily restored 1886-8 |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Spinetta Malaspina was a condottiere, or military commander, who died in 1352. His heirs later placed this memorial in the church that Spinetta founded outside the city. Its equestrian form is typical of Verona. Originally, the sculpture was probably brightly painted and gilded. The sarcophagus behind the row of figures is merely symbolic, indicating that the monument should be read as a cenotaph – a memorial with no body. |

| Associated object | 191A-1887 (Part) |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 191-1887 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | August 18, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest