Tapestry

1450-1500 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

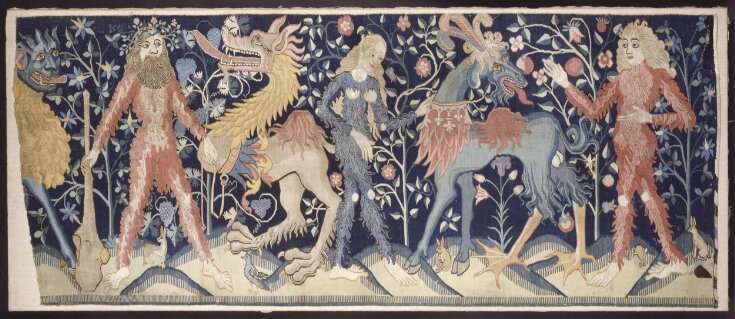

In the German speaking world of the late fourteenth to fifteenth centuries the role of Wild people and fabulous beasts was one of the most favoured themes in art, poetry and pageant. Tapestry wallhangings were one colourful and prestigious medium used to depict this subject. Wildness implied everything that went against the established framework of Christian society, representing the unconfined side of man's nature, but in a liberating, romantic sense rather than evil or dark.

Wildmen, wildwomen and mythical beasts, as shown in this tapestry, imply freedom, energy, natural instincts and pleasures. Noblemen and merchants liked to see this theme represented in their houses and castles on tiles, embroideries and tapestries and even on some utensils. The subject was not confined to the German-speaking lands and in England the Green(e) man, still occasionally used as the name of a public house (pub) may be seen as one representation of this theme, although usually shown as much less wild and exotic-looking than the Wildmen of the tapestry.

Wildmen, wildwomen and mythical beasts, as shown in this tapestry, imply freedom, energy, natural instincts and pleasures. Noblemen and merchants liked to see this theme represented in their houses and castles on tiles, embroideries and tapestries and even on some utensils. The subject was not confined to the German-speaking lands and in England the Green(e) man, still occasionally used as the name of a public house (pub) may be seen as one representation of this theme, although usually shown as much less wild and exotic-looking than the Wildmen of the tapestry.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Wool on wool warp (approximately 5 warps per cm.) |

| Brief description | Tapestry, woven in wool, Switzerland, 1450 - 1500; Wild folk with fabulous beasts |

| Physical description | Against a blue-black background two wild men and a wild woman alternate with three fabulous beasts. The tapestry - originally from the Saint Anna Kloster at Bruch, near Lucerne - has been cut at an angle along the left edge and is restored in the upper right corner. From left to right, on a foreground composed of small mounds, are: the head and foreleg of a beast with a blue body, thick yellow mane and cloven hoofs; a bearded wild man with shaggy, pinkish-red body hair, a wreath on his head, and a massive club in his right hand, holding a tether attached to the collar of an animal with a dragon-like head, yellow and red mane and a very long neck joined onto a pair of hind-legs but no forelegs; a wild woman with long flowing blonde hair and shaggy blue body growth, placing her hand on the neck of a blue-green animal with cloven fore-hoofs in front and webbed hind feet, a red mane, a plumed forelock, and a crown-shaped collar around its neck; and a young, beardless wild man with blonde hair and pinkish-red body growth gesturing toward the same beast. The dark blue background is decorated with vertical, tendrilled plants on tall stalks representing delphinium, a grapevine, roses (?), and pomegranates. A lily grows under the belly of the blue-green animal with plumes on top of its head. A blue-feathered bird, and various rabbits that either emerge out of or enter into holes enliven the barren, plantless landscape in the foreground. A full iconographical explication of the wild man's association with fabulous beasts has never been developed, and there are no known literary connections that might aid in its interpretation. Undoubtedly inspired by the mythical beasts of the Physiologus and bestiaries, these highly imaginative, composite creatures emerge in the late Middle Ages as the secular counterparts of the beasts in Christological symbolism, as amorous symbols, and as companions of the wild man in his woodland paradise. The development of this imagery can be traced in a group of fifteenth-century Swiss tapestries culminating in the present example. In one early type of these tapestries, generally dated between 1420 and 1440, the beasts are on leashes held by elegantly dressed gentlefolk and are understood as symbols of hidden vice. By the middle of the century, the wild folk have altogether replaced the courtly figures, and the wild man has become a symbol of eroticism and of an idyllic natural existence. In other contexts, the wild man was associated with symbolic animals, including the lion (loyalty and strength), unicorn (chastity, virtue, and feminine victory), and stag (faithfulness and honour). The substitution of wild men for the courtly figures alters the symbolism of the fabulous beasts from vice to eroticism. This point is explicit in a mid-fifteenth-century tapestry in the Osterreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, devoted to this subject (Inv. N. T. 9124), where love knots are scattered over the surface of the foliate background. In the Vienna tapestry the wild men play an additional role. The forest habitat and carefree life of the wild man were seen as an ideal natural existence far removed from the inequities and uncertainties of urban dwelling. In this escapist view of the woodland idyll, the fabulous beasts represent uncorrupted nature, the companions of the wild folk, who lament the falseness of man's existence. In this tapestry one wild man declares that he will keep to his animals and forsake the society of man; another says that they (the wild folk) will go through life with these animals as the society of man means nothing to them, while another asserts that mankind is completely treacherous and that they are better off with the animals. The misanthropic commentary of these elegantly turned-out wild folk and the fantastical appearance of their companions give the impression of playful whim. As with many examples of late medieval wild man imagery, the borderline between seriously intended symbolism and sardonic masquerade is ambiguous. In the present tapestry the wild folk and fabulous beasts, now distorted by imagination, perpetuate the same theme of the world's faithlessness. The lack of inscriptions may indicate that familiarity with the imagery by the middle of the fifteenth century obviated explanation. Modelled after an earlier tapestry (today also in the Osterreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna; T. 4940) the present example emphasizes the decorative qualities of the composition. The flora is reduced to a simple, airy pattern, while the beasts and wild folk are boldly silhouetted against a dark background. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label | Born to be wild

Long ago, people imagined that hairy, wild people lived freely in faraway forests around the world.

Not-so-wild people loved this idea, so sometimes decorated their homes with pictures of them.

[Young V&A, Imagine gallery short object label](2023) |

| Credit line | Purchased with the Captain H B Murray bequest |

| Object history | The Museum purchased this tapestry from F. A. Drey, who acquired it in the Albert Figdor Sale in 1930, Vienna. It originally came from the convent of St. Anna Kloster in Bruck, near Lucerne, being subsequently in the Meyer-am-Rhyn and Roman Abt Collections in Lucerne. Historical significance: In the German-speaking world of the late 14th to15th centuries the role of Wild People and fabulous beasts was the most favoured theme in art, poetry and pageant, beside romantic subjects and religion - although of course this was not confined to German-speaking lands. Wild men and beasts accordingly imply freedom, energy, the natural instincts. It became fashionable to identify oneself with savage things, to slip into the wild man's garb in pageants and masquerades. Remembered as the Bal des ardents but intended as a Bal des sauvages, a costumed ball was held to celebrate the marriage of a lady-in-waiting of Charles VI of France's queen in Paris, on January 28, 1393, where the King and five courtiers dressed up incognito as wildmen of the woods in costumes made of hemp and tar, and a torch inadvertently set their costumes afire. The courtiers died, but the King was saved by the Queen - romantically by the long train of her dress (image in Froissart 'Chronicles', fol. 176, BNF, FR 2646). But the erotic connotations of the Wildman are perhaps the strongest, and opposed the civilized ideals of the well-trained knight, of humble adulation and worship. The wild man is interpreted as a symbol of unruly passion; the conquest of feminine virtue by masculine force of insistence, but although the knight usually saves the lady, sometimes the noble heart of the wildman is revealed by his love to the lady or the love of the lady will tame and chain the wildman - as in marriage. |

| Historical context | An older tapestry, dated about 1450, woven from a similar cartoon, is in the Schweizerisches Landesmuseum in Zürich (Inv. no. LM 1178). |

| Production | Probably made in Lucerne or Basel. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | In the German speaking world of the late fourteenth to fifteenth centuries the role of Wild people and fabulous beasts was one of the most favoured themes in art, poetry and pageant. Tapestry wallhangings were one colourful and prestigious medium used to depict this subject. Wildness implied everything that went against the established framework of Christian society, representing the unconfined side of man's nature, but in a liberating, romantic sense rather than evil or dark. Wildmen, wildwomen and mythical beasts, as shown in this tapestry, imply freedom, energy, natural instincts and pleasures. Noblemen and merchants liked to see this theme represented in their houses and castles on tiles, embroideries and tapestries and even on some utensils. The subject was not confined to the German-speaking lands and in England the Green(e) man, still occasionally used as the name of a public house (pub) may be seen as one representation of this theme, although usually shown as much less wild and exotic-looking than the Wildmen of the tapestry. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | T.117-1937 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 2, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest