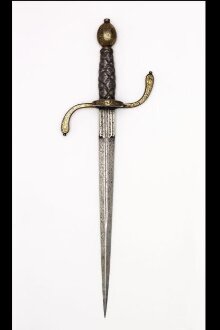

Dagger

ca. 1560 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This dagger would have once been twinned with a rapier, a long sword with a slender blade and elaborate hilt. The rapier and dagger combination was primarily designed for self-defence. The sixteenth-century rapier was both a slashing and stabbing weapon. Its accompanying dagger was used in the left hand for parrying and stabbing in close. The stiff slender blades of both were designed to pierce clothing rather than armour.

The raper and dagger were also male fashion accessories worn at court, in procession and about town. They projected an image of honour based on social standing and, if necessary, defended it in one-on-one combat. The private duel was one consequence of the development of the rapier and dagger.

New specialised fencing techniques were not welcomed by all. The conservative English defence expert, George Silver, felt a noble heritage of purpose-made war blades, clubs, flails and maces had been sacrificed at the altar of fashion as swords and daggers became faddish civilian accessories. ‘We like degenerate sonnes, have forsaken our forefathers vertues with their weapons.’

The intricate patterns of gold and silver wire on the surface of the pommel and knuckle guard is known as damascening. As the name implies, damascening originated in countries to the east of Europe, particularly Syria (Damascus), Persia, Egypt and Turkey. Imports of Islamic goods through Venice gave north Italian craftsmen plenty of inspiration when decorating anything from brass dishes to hand-warmers. The great Florentine sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini described his ‘burning desire’ to try his hand at making daggers ‘engraved by iron tools with patterns of beautiful foliage, in the Turkish style, which were nicely filled in with gold’.

The raper and dagger were also male fashion accessories worn at court, in procession and about town. They projected an image of honour based on social standing and, if necessary, defended it in one-on-one combat. The private duel was one consequence of the development of the rapier and dagger.

New specialised fencing techniques were not welcomed by all. The conservative English defence expert, George Silver, felt a noble heritage of purpose-made war blades, clubs, flails and maces had been sacrificed at the altar of fashion as swords and daggers became faddish civilian accessories. ‘We like degenerate sonnes, have forsaken our forefathers vertues with their weapons.’

The intricate patterns of gold and silver wire on the surface of the pommel and knuckle guard is known as damascening. As the name implies, damascening originated in countries to the east of Europe, particularly Syria (Damascus), Persia, Egypt and Turkey. Imports of Islamic goods through Venice gave north Italian craftsmen plenty of inspiration when decorating anything from brass dishes to hand-warmers. The great Florentine sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini described his ‘burning desire’ to try his hand at making daggers ‘engraved by iron tools with patterns of beautiful foliage, in the Turkish style, which were nicely filled in with gold’.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Steel damascened with gold |

| Brief description | Left hand dagger with a gold damascened steel hilt, Italy, ca. 1560 |

| Physical description | Main gauche with a steel hilt, gold damascened, with S-shaped quillons and loop guard, with a diamond section blade with a single medial fuller and a chiseled ricasso |

| Dimensions |

|

| Credit line | Francis Mallett Bequest |

| Historical context | This dagger would have once been twinned with a rapier, a long sword with a slender blade and elaborate hilt. The rapier and dagger combination was primarily designed for self-defence using fighting techniques developed in Italy that are the ancestors of modern fencing. The sixteenth-century rapier was both a slashing and stabbing weapon. Its accompanying dagger was used in the left hand for parrying and stabbing in close. The stiff slender blades of both were designed to pierce clothing rather than armour. The raper and dagger were also male fashion accessories worn at court, in procession and about town. They projected an image of honour based on social standing and, if necessary, defended it in one-on-one combat. The private duel was one consequence of the development of the rapier. In this sense, it is the epitome of the new sense of self fostered by the Renaissance. It was an emblem of personal vanity that settled disputes privately. The conservative English defence expert, George Silver, felt a noble heritage of purpose-made war blades, clubs, flails and maces had been sacrificed at the altar of fashion as swords and daggers became faddish civilian accessories. ‘We like degenerate sonnes, have forsaken our forefathers vertues with their weapons.’ Decorated daggers were not only lethal weapons but were works of art. They were part of the same aesthetic that produced decorated tapestries, furniture, silver and ceramics. The damascened ornament on the pommel and knuckle guard of this dagger was extremely popular in north Italian in the second half of the sixteenth century, but was also used widely in Europe. It is recognizable by the intricate patterns of gold and silver wire on the surface of darkened iron and steel. Sometimes the wire is inlaid in engraved channels, but more commonly it is overlaid and rubbed and hammered on. Occasionally the ornament sits proud of the surface and is more like an encrustation. As the name implies, damascening originated in countries to the east of Europe, particularly Syria (Damascus), Persia, Egypt and Turkey. Imports of Islamic goods through Venice gave north Italian craftsmen plenty of inspiration when decorating anything from brass dishes to hand-warmers, from inkstands to candlesticks and from breastplates to sword hilts. The great Florentine sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini described his ‘burning desire’ to try his hand at making daggers ‘engraved by iron tools with patterns of beautiful foliage, in the Turkish style, which were nicely filled in with gold’. |

| Summary | This dagger would have once been twinned with a rapier, a long sword with a slender blade and elaborate hilt. The rapier and dagger combination was primarily designed for self-defence. The sixteenth-century rapier was both a slashing and stabbing weapon. Its accompanying dagger was used in the left hand for parrying and stabbing in close. The stiff slender blades of both were designed to pierce clothing rather than armour. The raper and dagger were also male fashion accessories worn at court, in procession and about town. They projected an image of honour based on social standing and, if necessary, defended it in one-on-one combat. The private duel was one consequence of the development of the rapier and dagger. New specialised fencing techniques were not welcomed by all. The conservative English defence expert, George Silver, felt a noble heritage of purpose-made war blades, clubs, flails and maces had been sacrificed at the altar of fashion as swords and daggers became faddish civilian accessories. ‘We like degenerate sonnes, have forsaken our forefathers vertues with their weapons.’ The intricate patterns of gold and silver wire on the surface of the pommel and knuckle guard is known as damascening. As the name implies, damascening originated in countries to the east of Europe, particularly Syria (Damascus), Persia, Egypt and Turkey. Imports of Islamic goods through Venice gave north Italian craftsmen plenty of inspiration when decorating anything from brass dishes to hand-warmers. The great Florentine sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini described his ‘burning desire’ to try his hand at making daggers ‘engraved by iron tools with patterns of beautiful foliage, in the Turkish style, which were nicely filled in with gold’. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.65-1947 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | April 2, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest