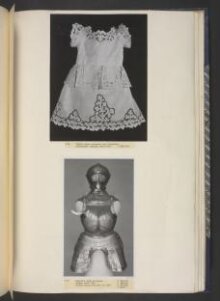

Backplate

1520-1540 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This backplate was once part of an armour for jousting or for battle. It is relatively light allowing for speed of movement. In a joust it was not a target area. Breastplates for jousting are much heavier.

Armour was highly specialised and purpose-made. Jousting and tournament armour was heavy to protect the specific target areas of head and body. Jousting was a dangerous sport and made up one of the final elements of a noble education. Separated by a barrier, opposing knights charged each other on horseback and aimed to break each other’s lance or to unseat each other. Helmets had narrow eye-slits to reduce the risk of facial injury. Tournaments were less ritualised than jousts and prepared knights for war. Teams of cavalry opposed each other and clashed with blunted swords, hammers and maces until judges chose a winner.

Battle armour was lighter and more flexible. For cavalry, an initial charge with a lance might be followed by close in-fighting with swords, maces and hammers so agility and speed of movement during chaotic, noisy and dangerous combats were essential.

Parade armour was showy and ostentatious. It was often intricately decorated and communicated majesty and authority during public celebrations such as coronations or the triumphal entry of princes into cities. The appearance of parade armour might be as much the work of the goldsmith as the armourer. It projected an image rather than protected a body.

Armour styles underwent an extraordinary change in the first decades of the sixteenth century whe this backplate was made. Gone was the sinuous, willowy grace of the previous decades as burly, overblown armours proclaiming a powerful upper body took over. Pinched waistlines, broad hips, square shoulders and straight necklines characterised armour in parallel with both men’s and women’s clothing.

The relationship between armour and clothing is close. Doublets of the period (forerunners of jackets today) were arranged in narrow pleats, an aesthetic that influenced armour decorated with corrugated ridges. This 'fluted' armour was highly popular in Germany and coincided with the later reign of the Emperor Maximilian I (1459-1519) whose armourers at Innsbruck were admired across Europe. The ridged surface has traditionally been credited with strengthening the armour against slashing sword blows but this appearance is primarily a fashion statement and decorated both man and horse. All such armour is plain below the knee in imitation of stockings, even for cavalry whose legs were vulnerable. This style also disappears by around 1540 when more restrained Spanish fashions started to dominate in Europe and make their presence felt on armour.

Armour was highly specialised and purpose-made. Jousting and tournament armour was heavy to protect the specific target areas of head and body. Jousting was a dangerous sport and made up one of the final elements of a noble education. Separated by a barrier, opposing knights charged each other on horseback and aimed to break each other’s lance or to unseat each other. Helmets had narrow eye-slits to reduce the risk of facial injury. Tournaments were less ritualised than jousts and prepared knights for war. Teams of cavalry opposed each other and clashed with blunted swords, hammers and maces until judges chose a winner.

Battle armour was lighter and more flexible. For cavalry, an initial charge with a lance might be followed by close in-fighting with swords, maces and hammers so agility and speed of movement during chaotic, noisy and dangerous combats were essential.

Parade armour was showy and ostentatious. It was often intricately decorated and communicated majesty and authority during public celebrations such as coronations or the triumphal entry of princes into cities. The appearance of parade armour might be as much the work of the goldsmith as the armourer. It projected an image rather than protected a body.

Armour styles underwent an extraordinary change in the first decades of the sixteenth century whe this backplate was made. Gone was the sinuous, willowy grace of the previous decades as burly, overblown armours proclaiming a powerful upper body took over. Pinched waistlines, broad hips, square shoulders and straight necklines characterised armour in parallel with both men’s and women’s clothing.

The relationship between armour and clothing is close. Doublets of the period (forerunners of jackets today) were arranged in narrow pleats, an aesthetic that influenced armour decorated with corrugated ridges. This 'fluted' armour was highly popular in Germany and coincided with the later reign of the Emperor Maximilian I (1459-1519) whose armourers at Innsbruck were admired across Europe. The ridged surface has traditionally been credited with strengthening the armour against slashing sword blows but this appearance is primarily a fashion statement and decorated both man and horse. All such armour is plain below the knee in imitation of stockings, even for cavalry whose legs were vulnerable. This style also disappears by around 1540 when more restrained Spanish fashions started to dominate in Europe and make their presence felt on armour.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | steel, fluted with roped borders |

| Brief description | Backplate from a cuirass, with a skirt of two plates, the third missing, Germany, 1520-40 |

| Physical description | Backplate with roped borders and converging flutes with an extension plate to which is attached the waist plate, three lames and tassets of four plates (the right hand restored) |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | This backplate was once part of an armour for jousting or battle. |

| Historical context | Armour was highly specialised and purpose-made. Battle armour was relatively light and flexible. For cavalry, an initial charge with a lance might be followed by close in-fighting with swords, maces and hammers so agility and speed of movement during chaotic, noisy and dangerous combats were essential. Jousting and Tournament armour was much heavier and protected specific target areas of head and body. Jousting was a dangerous sport and made up one of the final elements of a noble education. Separated by a barrier, opposing knights charged each other on horseback and aimed to break each other’s lance or to unseat each other. Helmets had narrow eye-slits to reduce the risk of facial injury. Tournaments were less ritualised than jousts and prepared knights for war. Teams of cavalry opposed each other and clashed with blunted swords, hammers and maces until judges chose a winner. Parade armour was showy and ostentatious. It was often intricately decorated and communicated majesty and authority during public celebrations such as coronations or the triumphal entry of princes into cities. The appearance of parade armour might be as much the work of the goldsmith as the armourer. It projected an image rather than protected a body. Armour styles underwent an extraordinary change in the first decades of the sixteenth century when this breastplate was made. Gone was the sinuous, willowy grace of the previous decades as burly, overblown armours proclaiming a powerful upper body took over. Pinched waistlines, broad hips, square shoulders and straight necklines characterised armour in parallel with both men’s and women’s clothing. The relationship between armour and clothing is close. Doublets of the period (forerunners of jackets today) were arranged in narrow pleats, an aesthetic that influenced armour decorated with corrugated ridges. This 'fluted' armour was highly popular in Germany and coincided with the later reign of the Emperor Maximilian I (1459-1519) whose armourers at Innsbruck were admired across Europe. The ridged surface has traditionally been credited with strengthening the armour against slashing sword blows but this appearance is primarily a fashion statement and decorated both man and horse. All such armour is plain below the knee in imitation of stockings, even for cavalry whose legs were vulnerable. This style also disappears by around 1540 when more restrained Spanish fashions started to dominate in Europe and make their presence felt on armour. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | This backplate was once part of an armour for jousting or for battle. It is relatively light allowing for speed of movement. In a joust it was not a target area. Breastplates for jousting are much heavier. Armour was highly specialised and purpose-made. Jousting and tournament armour was heavy to protect the specific target areas of head and body. Jousting was a dangerous sport and made up one of the final elements of a noble education. Separated by a barrier, opposing knights charged each other on horseback and aimed to break each other’s lance or to unseat each other. Helmets had narrow eye-slits to reduce the risk of facial injury. Tournaments were less ritualised than jousts and prepared knights for war. Teams of cavalry opposed each other and clashed with blunted swords, hammers and maces until judges chose a winner. Battle armour was lighter and more flexible. For cavalry, an initial charge with a lance might be followed by close in-fighting with swords, maces and hammers so agility and speed of movement during chaotic, noisy and dangerous combats were essential. Parade armour was showy and ostentatious. It was often intricately decorated and communicated majesty and authority during public celebrations such as coronations or the triumphal entry of princes into cities. The appearance of parade armour might be as much the work of the goldsmith as the armourer. It projected an image rather than protected a body. Armour styles underwent an extraordinary change in the first decades of the sixteenth century whe this backplate was made. Gone was the sinuous, willowy grace of the previous decades as burly, overblown armours proclaiming a powerful upper body took over. Pinched waistlines, broad hips, square shoulders and straight necklines characterised armour in parallel with both men’s and women’s clothing. The relationship between armour and clothing is close. Doublets of the period (forerunners of jackets today) were arranged in narrow pleats, an aesthetic that influenced armour decorated with corrugated ridges. This 'fluted' armour was highly popular in Germany and coincided with the later reign of the Emperor Maximilian I (1459-1519) whose armourers at Innsbruck were admired across Europe. The ridged surface has traditionally been credited with strengthening the armour against slashing sword blows but this appearance is primarily a fashion statement and decorated both man and horse. All such armour is plain below the knee in imitation of stockings, even for cavalry whose legs were vulnerable. This style also disappears by around 1540 when more restrained Spanish fashions started to dominate in Europe and make their presence felt on armour. |

| Associated objects |

|

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.116-1953 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | March 29, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest