Painting

ca. 1590-95 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

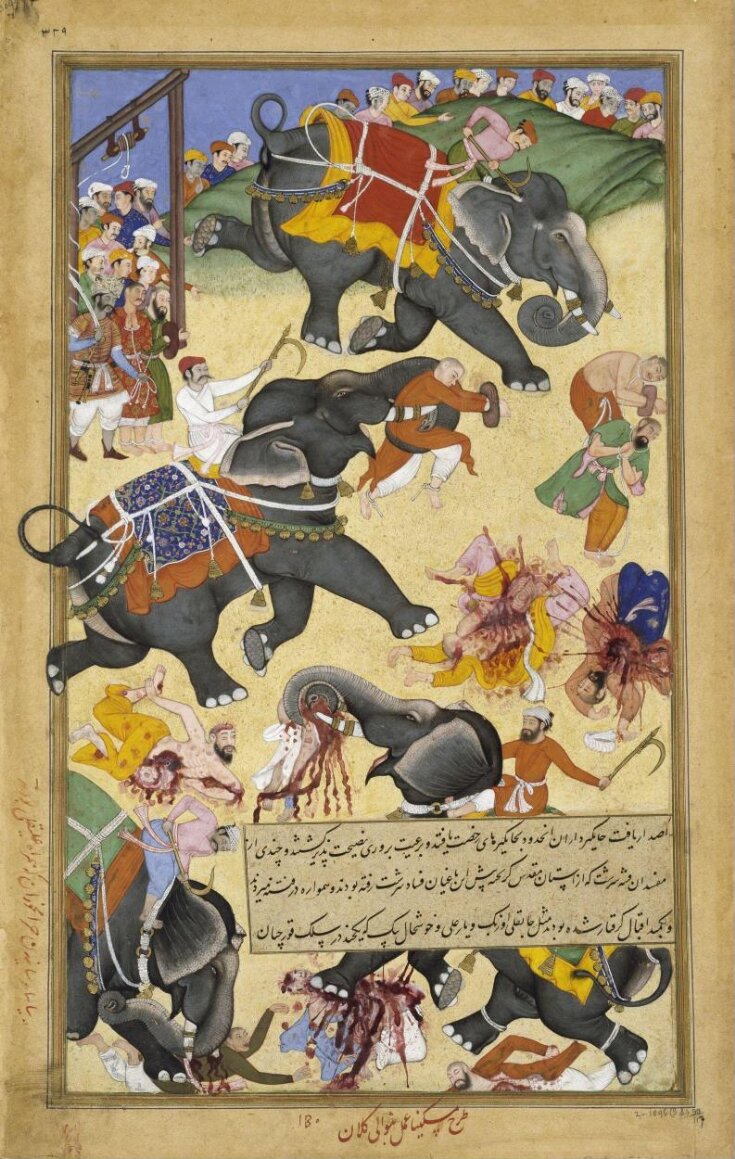

The composition of this painting was designed by the Mughal court artist Miskina and the details painted by Banwali the Elder. It is from the Akbarnama (Book of Akbar) .

Elephants played a crucial part in Mughal warfare, breaking through fortifications and killing enemy footsoldiers. They were also used to deliver capital punishment, as this painting vividly demonstrates. Ali Quli Shaibani had served Humayun, and his bravery in the early military campaigns of Akbar’s reign earned him a title and a valuable grant of land. However, his very public affair with Shaham Beg, formerly one of Humayun’s bodyguards, scandalised the court. He fell further into disgrace by marrying a prostitute who had also been Shaham Beg’s lover and living with both in a ménage a trois. Abu’l Fazl, writing with the benefit of hindsight, claimed that Ali Quli’s apparent loyalty was always insincere, though he did not rebel outright until 1566. Nevertheless, Akbar pardoned him after Mirza Rezavi Mirak, a close follower, begged forgiveness on Ali Quli’s behalf. The following year Ali Quli again rebelled, forcing Akbar to lead a small force to crush him. Ali Quli died in the battle, and his leading supporters were captured and executed by elephants before the emperor. Mirza Rezavi Mirak was among the captives but the elephant’s mahout was ordered not to kill him. Instead, the huge animal simply played with him. This terrifying ordeal was repeated for five consecutive days until Mirza Rezavi Mirak was freed.

[AKbarnama, English translation: Beveridge, vol. II, pp. 398, 426-36]

The Akbarnama was commissioned by Akbar as the official chronicle of his reign. It was written in Persian by his court historian and biographer, Abu’l Fazl, between 1590 and 1596, and the V&A’s partial copy of the manuscript is thought to have been illustrated between about 1592 and 1595. This is thought to be the earliest illustrated version of the text, and drew upon the expertise of some of the best royal artists of the time. Many of these are listed by Abu’l Fazl in the third volume of the text, the A’in-i Akbari, and some of these names appear in the V&A illustrations, written in red ink beneath the pictures, showing that this was a royal copy made for Akbar himself. After his death, the manuscript remained in the library of his son Jahangir, from whom it was inherited by Shah Jahan.

The V&A purchased the manuscript in 1896 from Frances Clarke, the widow of Major General John Clarke, who bought it in India while serving as Commissioner of Oudh between 1858 and 1862.

Elephants played a crucial part in Mughal warfare, breaking through fortifications and killing enemy footsoldiers. They were also used to deliver capital punishment, as this painting vividly demonstrates. Ali Quli Shaibani had served Humayun, and his bravery in the early military campaigns of Akbar’s reign earned him a title and a valuable grant of land. However, his very public affair with Shaham Beg, formerly one of Humayun’s bodyguards, scandalised the court. He fell further into disgrace by marrying a prostitute who had also been Shaham Beg’s lover and living with both in a ménage a trois. Abu’l Fazl, writing with the benefit of hindsight, claimed that Ali Quli’s apparent loyalty was always insincere, though he did not rebel outright until 1566. Nevertheless, Akbar pardoned him after Mirza Rezavi Mirak, a close follower, begged forgiveness on Ali Quli’s behalf. The following year Ali Quli again rebelled, forcing Akbar to lead a small force to crush him. Ali Quli died in the battle, and his leading supporters were captured and executed by elephants before the emperor. Mirza Rezavi Mirak was among the captives but the elephant’s mahout was ordered not to kill him. Instead, the huge animal simply played with him. This terrifying ordeal was repeated for five consecutive days until Mirza Rezavi Mirak was freed.

[AKbarnama, English translation: Beveridge, vol. II, pp. 398, 426-36]

The Akbarnama was commissioned by Akbar as the official chronicle of his reign. It was written in Persian by his court historian and biographer, Abu’l Fazl, between 1590 and 1596, and the V&A’s partial copy of the manuscript is thought to have been illustrated between about 1592 and 1595. This is thought to be the earliest illustrated version of the text, and drew upon the expertise of some of the best royal artists of the time. Many of these are listed by Abu’l Fazl in the third volume of the text, the A’in-i Akbari, and some of these names appear in the V&A illustrations, written in red ink beneath the pictures, showing that this was a royal copy made for Akbar himself. After his death, the manuscript remained in the library of his son Jahangir, from whom it was inherited by Shah Jahan.

The V&A purchased the manuscript in 1896 from Frances Clarke, the widow of Major General John Clarke, who bought it in India while serving as Commissioner of Oudh between 1858 and 1862.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Painted in opaque watercolour and gold on paper |

| Brief description | Painting, Akbarnama, trained elephants execute followers of Khan Zaman, outline by Miskina, painting Banwali the Elder, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, Mughal, ca. 1590-95 |

| Physical description | Painting, in opaque watercolour and gold on paper, trained elephants executing Akbar's prisoners, the followers of Khan Zaman in 1567. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Content description | Trained elephants executing Akbar's prisoners, the followers of Khan Zaman in 1567. |

| Styles | |

| Marks and inscriptions | Note Contemporary librarian's attribution in Persian written beneath the image at the bottom of the page in red ink. Translation 'composition by Miskina/work [painting] by Banwali the Elder' Transliteration 'Tarh: Miskina/Amal: Banwali Kalan' |

| Credit line | Purchased from Mrs. Clarke, The Dingle, Sydenham Hill, S. E |

| Object history | The Akbarnama, or "Book of Akbar", was commissioned by the emperor Akbar as the official chronicle of his reign. It was written by 1590 and 1596 and is thought to have been illustrated between ca. 1592 and 1594 by at least forty-nine different artists from Akbar's studio. After Akbar's death in 1605, the manuscript remained in the library of his son, Jahangir (r.1605-1627) and later Shah Jahan (r.1628-1658). The Victoria and Albert Museum purchased it in 1896 from Mrs. Frances Clarke, the widow of Major General John Clarke, an official who had been the Commissioner in Oudh province between 1858 and 1862. Historical significance: It is thought to be the first illustrated copy of the Akbarnama. It drew upon the expertise of some of the best royal painters of the time, many of whom receive special mention by Abu'l Fazl in the A'in-i-Akbari, the third volume of the Akbarnama. The inscriptions in red ink on the bottom of the paintings refer to the artists and indicate that this was a royal copy. Purchased from Mrs. Clarke, The Dingle, Sydenham Hill, S. E. This acquisition information reflects that found in the Museum records (Asia Department registers and/or Central Inventory) as part of a 2023 provenance research project. Registered Papers: 85488/95 |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Association | |

| Literary reference | Akbarnama |

| Summary | The composition of this painting was designed by the Mughal court artist Miskina and the details painted by Banwali the Elder. It is from the Akbarnama (Book of Akbar) . Elephants played a crucial part in Mughal warfare, breaking through fortifications and killing enemy footsoldiers. They were also used to deliver capital punishment, as this painting vividly demonstrates. Ali Quli Shaibani had served Humayun, and his bravery in the early military campaigns of Akbar’s reign earned him a title and a valuable grant of land. However, his very public affair with Shaham Beg, formerly one of Humayun’s bodyguards, scandalised the court. He fell further into disgrace by marrying a prostitute who had also been Shaham Beg’s lover and living with both in a ménage a trois. Abu’l Fazl, writing with the benefit of hindsight, claimed that Ali Quli’s apparent loyalty was always insincere, though he did not rebel outright until 1566. Nevertheless, Akbar pardoned him after Mirza Rezavi Mirak, a close follower, begged forgiveness on Ali Quli’s behalf. The following year Ali Quli again rebelled, forcing Akbar to lead a small force to crush him. Ali Quli died in the battle, and his leading supporters were captured and executed by elephants before the emperor. Mirza Rezavi Mirak was among the captives but the elephant’s mahout was ordered not to kill him. Instead, the huge animal simply played with him. This terrifying ordeal was repeated for five consecutive days until Mirza Rezavi Mirak was freed. [AKbarnama, English translation: Beveridge, vol. II, pp. 398, 426-36] The Akbarnama was commissioned by Akbar as the official chronicle of his reign. It was written in Persian by his court historian and biographer, Abu’l Fazl, between 1590 and 1596, and the V&A’s partial copy of the manuscript is thought to have been illustrated between about 1592 and 1595. This is thought to be the earliest illustrated version of the text, and drew upon the expertise of some of the best royal artists of the time. Many of these are listed by Abu’l Fazl in the third volume of the text, the A’in-i Akbari, and some of these names appear in the V&A illustrations, written in red ink beneath the pictures, showing that this was a royal copy made for Akbar himself. After his death, the manuscript remained in the library of his son Jahangir, from whom it was inherited by Shah Jahan. The V&A purchased the manuscript in 1896 from Frances Clarke, the widow of Major General John Clarke, who bought it in India while serving as Commissioner of Oudh between 1858 and 1862. |

| Bibliographic reference | Asok Kumar Das, ‘The Elephant in Mughal Painting’ in Som Prakash Verma, ed., Flora and Fauna in Mughal Art, Marg Publications, Bombay, 1999, fig. 7 p. 43. |

| Other number | 150 - inscription/original number |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | IS.2:90-1896 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 6, 1998 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest