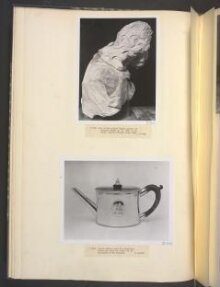

The Prophet Haggai

Bust

ca. 1285-1297 (made)

ca. 1285-1297 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Giovanni Pisano designed a revolutionary façade for Siena Cathedral. It housed a series of monumental figures in arcades. This marble head formed the upper part of one of those full-length statues. The sculptor allowed for the fact that the figure was to be placed high up on the church by carving it with great boldness. They form a landmark in the history of sculpture and are conceived with such heroic breadth and carved with such freedom that in discussing them reference has repeatedly been made to the work of Michelangelo.

The importance of the Siena statues in the history of sculpture is difficult to overstate. The facade is the single example in Italy of Gothic monumental sculpture integrated in a comprehensive architectural scheme, and though their source of inspiration stemmed from France, the statues with which it was decorated between 1284 and 1295 are some of the most personal and most moving of all sculptures. The statues for which Giovanni Pisano was in whole or in part responsible were confined to the first register of the facade, and represent prophets and prophetesses with inscriptions relating to the Virgin to whom the Cathedral is dedicated.

The present piece can be confidently associated with the full-length figure of the prophet Haggai because of the scroll held in his hand.

This is the only work firmly attributed to Giovanni Pisano outside Italy.

The importance of the Siena statues in the history of sculpture is difficult to overstate. The facade is the single example in Italy of Gothic monumental sculpture integrated in a comprehensive architectural scheme, and though their source of inspiration stemmed from France, the statues with which it was decorated between 1284 and 1295 are some of the most personal and most moving of all sculptures. The statues for which Giovanni Pisano was in whole or in part responsible were confined to the first register of the facade, and represent prophets and prophetesses with inscriptions relating to the Virgin to whom the Cathedral is dedicated.

The present piece can be confidently associated with the full-length figure of the prophet Haggai because of the scroll held in his hand.

This is the only work firmly attributed to Giovanni Pisano outside Italy.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | The Prophet Haggai (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Carved marble |

| Brief description | Bust, marble, of the Prophet Haggai, by Giovanni Pisano, Italy (Siena), ca. 1285-1297 |

| Physical description | Marble bust of the Prophet Haggai. The Prophet is depicted as old and bearded, and his head is turned in three-quarter profile. In his left hand he holds a scroll, and he wears a cloak around his shoulders. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | 'et veniet desideratus cunctuis gentibus et implebo domum istam gloria' |

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Purchased with Art Fund support, and the aid of a special grant from the exchequer |

| Object history | Bought from P&D Colnaghi & Co Ltd, 14 New Bond Street for £23,000 (special grant of £15,000, contribution from the NACF of £5000, remainder from Museum funds). RF 63/1183 This marble head formed the upper part of a full-length statue. It was carved as one of a series of fourteen Prophets and Prohetesses for the facade of the Cathedral, Siena (twelve of which are now in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo at Siena) . The sculptures were executed between 1284 and Giovanni Pisano's departure from Siena in 1296. The piece can be confidently associated with the full-length figure of the prophet Haggai because of the scroll held in his hand. The two letters on the scroll can be identified with the last two letters of the first line of the inscription held by the Haggai: "Et veniET desideratus cunctis gentibus et implebo domum istan gloria". A label with the number 125 was, at the time of purchase, attached to the back of the sculpture. This was identified by the Rector of Siena Cathedral as of the type used by the museum of the Opera del Duomo in the 19th century and must therefore have spent some time in their store rooms. Nothing is known of the object's history between then and it's purchase by the museum. Historical significance: The series of statues from the facade of Siena Cathedral, from which this figures comes, form a landmark in the history of sculpture. They are conceived with such heroic breadth and carved with such freedom that in discussing them reference has repeatedly been made to the work of Michelangelo. From the purchase justification, J P-H 20/5/63: "As you are aware, I spent May 14th – 18th in Siena in connection with the bust of a prophet (Fig.A) by Giovanni Pisano which is now on exhibition at Colnaghi’s and which has been reserved for the Museum. The bust was photographed in detail at the Museum before I left, and on the basis of these photographs it was accepted both by Enzo Carli, the Superintendent of Fine Art at Siena (who has written on Giovanni Pisano and whose acquaintance with the Siena figures is particularly close), and Conte del Vescovo Sterbini, the Rector of Siena Cathedral, that the carving originally formed part of the sculptures executed by Giovanni Pisano for the façade of the Cathedral. The Rector identified the label with the manuscript number 125 stuck on the shoulder (Fig. B) as one used by the Opera del Duomo in Siena in the late nineteenth century. The figure (which is carved in the same soft, rather friable marble as the statues still at Siena) as therefore at one time the property of the Opera of Siena Cathedral. The importance of the Siena statues in the history of sculpture is difficult to overstate. The facade is the single example in Italy of Gothic monumental sculpture integrated in a comprehensive architectural scheme, and though their source of inspiration stemmed from France, the statues with which it was decorated between 1284 and 1295 are some of the most personal and most moving of all sculptures. The statues for which Giovanni Pisano was in whole or in part responsible were confined to the first register of the facade, and represent prophets and prophetesses with inscriptions relating to the Virgin to whom the Cathedral is dedicated. They seem to have been carved after the great half-length figures of saints and apostles on the Baptistry at Pisa, and precede the pulpit at Pistoia which was completed in 1301, and it is from them that our knowledge of Giovanni Pisano's mature style on a monumental scale depends. They are conceived with such heroic breadth and carved with such audacity that in discussing them, reference has repeatedly been made to the work of Michelangelo. The condition of the façade statues seems to have caused difficulty from comparatively early times, and in the case of only three is the entire figure, from head to feet, preserved. The base of the most damaged of the figures, the Balaam, may have been restored as early as the sixteenth century, and there is at least one example of eighteenth century restoration among the figures, the head of Aristotle. An extensive campaign of restoration was undertaken by the sculptor Antonio Manetti in 1836 (for this see Romagnoli, Cenno storico-artistico di Siena e suoi suburbi, Siena, 1840, p.6) and the rate of restoration was accelerated after the appointment in 1867 of a supervisory Commissione di Belle Arti. In the course of this work many of the figures were removed from the façade and wrongly replaced, the figure of Moses, for example, was replaced in the upper register in the position originally intended for the statue of St. Mark. The original position for which the statues were designed can be established from the names inscribed beside them on the wall at shoulder height. The present figure could therefore have been removed from the façade at any time after 1836. Of the fourteen figures carved by Giovanni Pisano for the first register of the facade one, the Daniel, has disappeared, and another, the Haggai, was replaced by another figure from the upper part of the façade, and the present bust must therefore be from the upper part of the façade and form the upper part of one or other of these statues. The possibility that the present figure is identical with the Daniel can be ruled out, since the scroll held by the Daniel opened with the verse: “Et post hebomades sexaginta duas…” and would be inconsistent with the letters ET which appear on the present scroll. One of the figures at Siena, the Mary sister of Moses, is constructed differently from the rest, in that the head is thrust forwards in a manner exactly analogous to that of the present figure. The reason for this is that the Mary sister of Moses was one of the three statues originally sited on the south end of the façade. It would be a reasonable inference that the present Prophet was destined for a similar position on the north, that is for the place originally occupied by the Haggai. The figures on the façade are planned in pairs, whose poses correspond. Thus on the front of the church the David and Solomon – and the Moses and the Joshua – face each other as though engaged in some form of colloquy. The Isaiah on the north side of the facade (Fig.C) is shown with the head turned over the right shoulder and the Haggai must have been shown with the head turned over the left shoulder, like the present Prophet. On formal grounds there is therefore a strong case for identifying the figure as the Haggai. The height of the letters on the scrolls held by the Siena Prophets not unnaturally varies in the ratio of the length of the inscription. Thus in the Habakkuk, where the inscription is short, they measure 8.5cm, while in the Plato, where the inscription is long, they measure 5.6cm. The width of the letters is proportionate to the height, so that each line of the inscription on the Habakkuk comprises six letters, and each line of the inscription on the Plato comprises eight. The height of the letters on the scroll held by the new Prophet is 5.5cm, and it is thus likely that the two letters ET which are preserved were preceded by six other letters. The inscription held by the Haggai came from Haggai 2, 8 and read: “et veniET desideratus cunctuis gentibus et implebo domum istam gloria.” Examination under ultra-violet light gives no reason to suppose that the E or T have been recut, and the identification of the present figure as the upper part of the Haggai is therefore inescapable. The statues now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo are not uniform in structure, scale or size, and the basis of comparison with the new Prophet is therefore to some extent arbitrary. The width of the figure measured across the shoulders (50cm) is roughly the same as that of the Isaiah (55cm), and the heights of the two heads correspond. The depth of the figure, measured from the back of the block to the front plane, is 51cm; the corresponding measurement for the Mary sister of Moses at Siena is 49cm. Most of the Siena figures are hollowed out behind from a point level with or below the shoulder blades tot he base, but one of them, the Sibyl, is carved fully in the round, and another, the Balaam, is in the round save for a narrow excavated area on the right hand side. The treatment of the back of the Prophet is perfectly consistent with that of the Siena figures. All the figures from the façade are carved from a single block. There is every reason to suppose that the present figure was originally carved in the same way, and that the division at the base of the neck is due to a horizontal split, which was cut through when the figure was removed from its original site. There is abundant evidence from the figures in the Operal del Duomo that the marble of which they are composed was prone to split horizontally, and secondly that when it did so in a manner which was detrimental to stability a clean cut was made. In the Mary sister of Moses (Fig. D) an incipient horizontal fracture can be followed round the figure slightly below the level of the shoulders, and there is another round the crown on the head. With the Aristotle (Fig. E) the originally head has been lost as the result of horizontal fracture at the base of the neck. There are also analogies in the Siena statues for the irregular horizontal fracture a the base of the new figure. All those figures of which the lower parts date from the nineteenth century have been cut through horizontally, and in many cases the weathered edge of the original marble has crumbled as it has done here. Since the statues in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo were exposed on the façade of the Cathedral for a much longer time that the present figure their condition is less good. The definition of the form is blunter (in some cases nothing but the generalised shape of the head had been preserved ) and much of the detail has been effaced. None the less all of the formal idiodsyncracies of the present figure recur. Thus the form of the nose agrees very closely with that of the Isaiah, the scooping-out of the area above the nose occurs again in the Simeon (Fig.F) and the David (where the central section of the beard has been broken and made up), the carving of the eyes is closely analogous to that of the much damaged Plato, and the pockets beneath the eyes recur in the Simeon (Fig.F). The technical expedients employed in the present figure – the vertical drilling behind the neck, the deeply cut outline of the left sleeve, and the handling of the hand and mouth – are one and all paralleled in the Siena statues. The drilling in the fringe of the robe is especially close to those parts of the fringe of the robe of the Moses that were not make up in the nineteenth century. A particularly telling comparison can be made between the hand of the Prophet (Fig. G), where the bases of the third and fourth fingers are connected by a web of marble which has not been removed, and the hand of the Sibyl, which is treated in precisely the same way. There is a rather striking absence of consistency in the epigraphy of the scrolls held by the Siena figures. In at least one case --- the Moses, where the whole body has been smoothed down --- the inscription has been extensively recut, but in others the scrolls have not been tampered with , and some of these offer exact analogies for the form of the E and T on the present scroll. Perhaps it may be permissible to add a final word about the quality of the new figure. The Siena statues are universally regarded as the finest surviving examples of Italian Gothic monumental sculpture. Owing to their deteriorated state, however, there is is among them not one single head which registers with such directness of such force. Indeed it is from the upper part of the Haggai alone that the artist’s dramatic intention and empirical technique can properly be judged. Some impression of the impact of this extraordinary figure can be gained from the fact that the art critic of the Daily Telegraphy, reviewing the exhibition of Old Masters at Colnaghi’s where it is at present shown, describes it as “one of the greatest works of art to appear on the market in recent years….It represents the fullest emotional expression of Gothic sculpture and in a strange way, looks forward to Michelangelo.” The opportunity to acquire a major work by the greatest Italian Gothic sculptor has never occurred before (there is indeed no autograph work by Giovanni Pisano outside Italy) and will not recur, and it would be inexcusable if the occasion to secure this masterpiece were to be lost. I have been able to learn nothing of the history of the figure between the time of its removal from the magazine of the Opera del Duomo in Siena and the present day. When Keller prepared his definitive study of the Siena façade (H. Keller, “Die Bauplastik des Sieneser Doms,” in Kunstgeschichtliches Jahrbuch der Biblioteca Herziana, I, 1937, pp.141-221), he was informed by Bacci, then Soprintendente alle Belle Arti in Siena and later Rector of the Cathedral, that “haben sich Akten uber die Restaurierungsarbeiten weder in der Soprintendenza noch im staatarchiv in Siena erhalten.” This is strictly correct, but a schedario of the contents of the Archivio dell’Opera del Duomo deposited in the Archivio di Stato lists a number of volumes in the Cathedral archives with apyments relating to work on the Duomo façade. The Archivio dell’Opera del Duomo is in a state of indescribably confusion, but in the account books which I could trace no details are given of the specific restorations for which payments were made. The only inventories of the Opera del Duomo that were available date from the 1880s, and these are again so carelessly compiled that individual figures cannot be identified. The present figure was unknown both to Carli and to Sterbini. According to Colnaghi, it was recently offered by a responsible Roman dealer Sestieri (from whom we have purchased object in the past) to the Cleveland Museum of Art at a price of $100,000. Unaccountably it was turned down by Cleveland (where its unique significance seems not to have been recognised), and is now on sale for £28,000. As a result of discussion with Thesiger at Colnaghi’s, this price has been reduced to £23,000 if it is bought for the Museum. I have agreed that this figure should be regarded as confidential. Since this one of the most important sculptures, and fare the most important Gothic sculpture, that has ever been offered for sale to the Museum, the price does not seem to be excessive, and I should personally have no hesitation in recommending it for purchase at a far higher price. It will be necessary to apply for a special grant of £15,000, leaving a balance of £8,000 to be raised jointly from the Purchase Grant and from the National Art-Collections Fund." The sculptures on the facade of Siena Cathedral are carved from soft, friable marble and are subject cracking particularly horizontally. A campaign of restoration was initiated in 1836. This is the date when it is likely that the present piece was removed from the facade. It has therefore been subject to more than a hundred years less weathering than the rest of the sculptures. The surviving definition of detail is therefore unique in its preservation. This is the only work firmly attributed to Giovanni Pisano outside Italy. Press criticism of the bust while on show at Colnaghi's prior to its purchase by the museum: Daily Telegraph describes it as "one of the greatest works of art to appear on the market in recent years...It represents the fullest emotional expression of Gothic sculpture, and in a strange way, looks forward to Michelangelo". Daily Express comments: "I consider it a splendid bargain. Short of Michelangelo's bas-relief of the Virgin and Child owned by the Royal Academy...I can think of no work of art in stone in this country that could enrich more signally the Museum's magnificent collection of Italian sculpture". |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Giovanni Pisano designed a revolutionary façade for Siena Cathedral. It housed a series of monumental figures in arcades. This marble head formed the upper part of one of those full-length statues. The sculptor allowed for the fact that the figure was to be placed high up on the church by carving it with great boldness. They form a landmark in the history of sculpture and are conceived with such heroic breadth and carved with such freedom that in discussing them reference has repeatedly been made to the work of Michelangelo. The importance of the Siena statues in the history of sculpture is difficult to overstate. The facade is the single example in Italy of Gothic monumental sculpture integrated in a comprehensive architectural scheme, and though their source of inspiration stemmed from France, the statues with which it was decorated between 1284 and 1295 are some of the most personal and most moving of all sculptures. The statues for which Giovanni Pisano was in whole or in part responsible were confined to the first register of the facade, and represent prophets and prophetesses with inscriptions relating to the Virgin to whom the Cathedral is dedicated. The present piece can be confidently associated with the full-length figure of the prophet Haggai because of the scroll held in his hand. This is the only work firmly attributed to Giovanni Pisano outside Italy. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | A.13-1963 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 25, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest