Noli Me Tangere

Panel

1946 (made)

1946 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

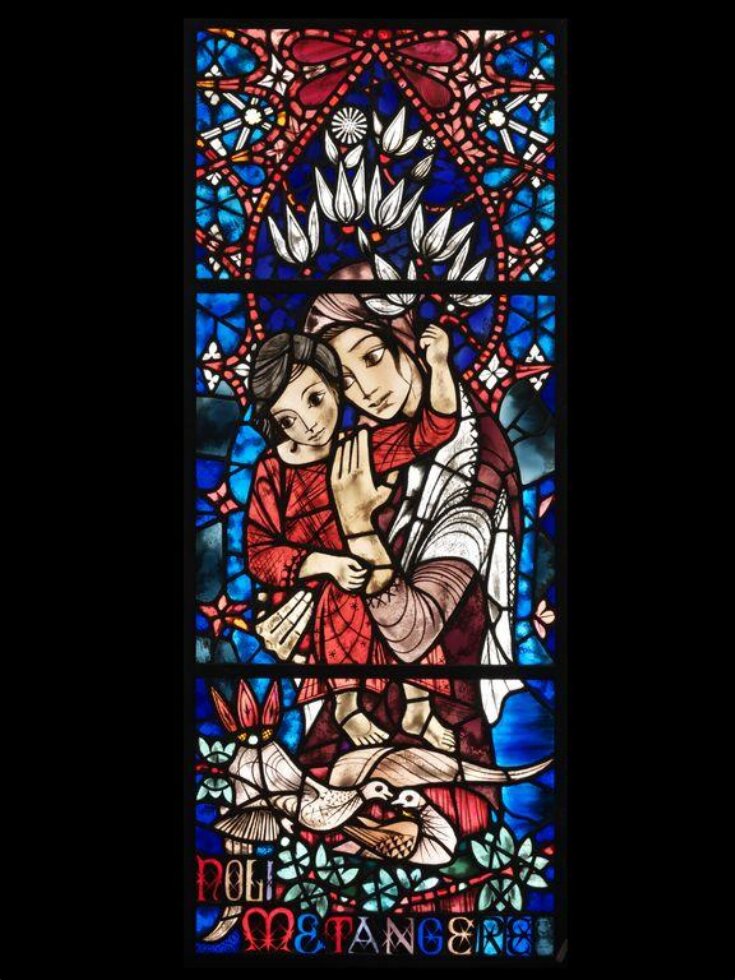

The Hungarian-born Ervin Bossanyi developed his stained-glass skills while working in Lübeck in Germany between 1919 and 1929. In 1924 his wife gave birth to a son, and it was then that he began to use the ‘mother and son’ theme that appears throughout his career. He believed that a mother’s love was unselfish and represented the core of human goodness.

Bossanyi moved his family to England in 1934 and was noticed by a fellow Hungarian, Rozsike Rothschild, who became his patroness. Some of his first works in England were for London University and the new Uxbridge Station.

He began experimenting with new types of glass-painting pigments through the auspices of the firm of Hancocks in Worcester. Hancocks, a specialist paint manufacturer, had been taken over by the Johnson Matthey Organisation, which controlled the Whitefriars Glassworks. Johnson Matthey commissioned Bossanyi to make a glass panel painted with the new pigments he had worked on with Hancocks.

The result was the Noli me tangere panel on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Bossanyi made this panel when he learnt that his 93-year-old mother had died in a concentration camp.

Bossanyi describes this work: ‘I wanted in this glass only the symbols of motherly and filial love, the building of the family home and the deep relationship between the human child and all beauty and grace nature produces and which must not be hurt or destroyed. In this sense should the inscription [‘Noli me tangere’] be understood’.

Bossanyi moved his family to England in 1934 and was noticed by a fellow Hungarian, Rozsike Rothschild, who became his patroness. Some of his first works in England were for London University and the new Uxbridge Station.

He began experimenting with new types of glass-painting pigments through the auspices of the firm of Hancocks in Worcester. Hancocks, a specialist paint manufacturer, had been taken over by the Johnson Matthey Organisation, which controlled the Whitefriars Glassworks. Johnson Matthey commissioned Bossanyi to make a glass panel painted with the new pigments he had worked on with Hancocks.

The result was the Noli me tangere panel on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Bossanyi made this panel when he learnt that his 93-year-old mother had died in a concentration camp.

Bossanyi describes this work: ‘I wanted in this glass only the symbols of motherly and filial love, the building of the family home and the deep relationship between the human child and all beauty and grace nature produces and which must not be hurt or destroyed. In this sense should the inscription [‘Noli me tangere’] be understood’.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Noli Me Tangere (assigned by artist) |

| Materials and techniques | Clear and coloured glass, painted |

| Brief description | Clear and coloured glass panel, painted, depicting a mother and child. Made by Ervin Bossanyi, English, 1946 |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | Noli Me Tangere

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Given by Johnson Matthey & Co. |

| Object history | Bossanyi began experimenting with new types of glass-painting pigments through the auspices of the firm of Hancocks in Worcester. Hancocks, a specialist paint manufacturer, had been taken over by the Johnson Matthey Organisation who controlled the Whitefriars Glassworks. Bossanyi was commissioned by Johnson Matthey to make a glass panel painted with the new pigments he had worked on with Hancocks. The result was the 'Noli Me Tangere' panel on display in the V&A. Bossanyi made this panel at the time he learnt that his 93-year old mother had been taken to a concentration camp where she had died. Bossanyi describes this work: I wanted in this glass only the symbols of motherly and filial love, the building of the family home and the deep relationship between the human child and all beauty and grace nature produces and which must not be hurt or destroyed. In this sense should the inscription ['Noli me tangere'] be understood. In the 1970s (at least) this panel and another work by Bossanyi (museum number) were on display together on a staircase. |

| Historical context | Bossanyi developed his stained glass skills while working in Lubeck in Germany between 1919 and 1929. He learnt from Carl Berkentien, an established decorative glass artist in Lubeck. Bossanyi and Berkentien restored old church glass and had commissions for new work for the churches in the town. The skills he acquired during this time included engraving, etching, staining and painting on glass. In 1924, his wife gave birth to his son and it is from this time that the ‘mother and son’ theme begins to appear in many of his works. Bossanyi would revisit this theme throughout his career. He believed that a mother’s love was unselfish and represented the core of human goodness. From 1929 until 1934, Bossanyi worked primarily in Hamburg. His work was very well received. Unfortunately, much of this was destroyed in the second world war. He moved his family to England in 1934 and was noticed by a fellow Hungarian, Rozsike Rothschild, who became his patroness. She introduced him to influential people such as Sir Evan Charteris, Chairman of the Tate Gallery Trustees. Some of Bossanyi’s first works in England were for the London University and the new Uxbridge Station. Bossanyi began experimenting with new types of glass-painting pigments through the auspices of the firm of Hancocks in Worcester. Hancocks, a specialist paint manufacturer, had been taken over by the Johnson Matthey Organisation who controlled the Whitefriars Glassworks. Bossanyi was commissioned by Johnson Matthey to make a glass panel painted with the new pigments he had worked on with Hancocks. The result was the ‘Noli Me Tangere’ panel on display in the V&A. Bossanyi made this panel at the time he learnt that his 93-year old mother had been taken to a concentration camp where she had died. Bossanyi describes this work: I wanted in this glass only the symbols of motherly and filial love, the building of the family home and the deep relationship between the human child and all beauty and grace nature produces and which must not be hurt or destroyed. In this sense should the inscription [‘Noli me tangere’] be understood. In the 1950s Bossanyi was commissioned to make eight windows for the Michaelhouse Chapel, Natal in South Africa. The rose window was painted with the head of Christ, his hands raised in blessing and holding two birds, one black and one white. This was to symbolise the joining of the two racial groups in South Africa. Throughout his career, Bossanyi was concerned about getting the right balance of the play of light through his glass. He describes his work: When the sun comes through at the right angle a great number of glasses will send forth quite brilliant-like colours. These I made by chips of very thick colour glassslabs, faceted and bevelled to fit into the lead, by the diamond grinding wheel. At this time Bossanyi’s reputation as a major stained glass artist was secure. He was commissioned to create works by both Canterbury and York Cathedrals. |

| Production | Panel is dated 1946 |

| Summary | The Hungarian-born Ervin Bossanyi developed his stained-glass skills while working in Lübeck in Germany between 1919 and 1929. In 1924 his wife gave birth to a son, and it was then that he began to use the ‘mother and son’ theme that appears throughout his career. He believed that a mother’s love was unselfish and represented the core of human goodness. Bossanyi moved his family to England in 1934 and was noticed by a fellow Hungarian, Rozsike Rothschild, who became his patroness. Some of his first works in England were for London University and the new Uxbridge Station. He began experimenting with new types of glass-painting pigments through the auspices of the firm of Hancocks in Worcester. Hancocks, a specialist paint manufacturer, had been taken over by the Johnson Matthey Organisation, which controlled the Whitefriars Glassworks. Johnson Matthey commissioned Bossanyi to make a glass panel painted with the new pigments he had worked on with Hancocks. The result was the Noli me tangere panel on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Bossanyi made this panel when he learnt that his 93-year-old mother had died in a concentration camp. Bossanyi describes this work: ‘I wanted in this glass only the symbols of motherly and filial love, the building of the family home and the deep relationship between the human child and all beauty and grace nature produces and which must not be hurt or destroyed. In this sense should the inscription [‘Noli me tangere’] be understood’. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | C.58-1955 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | October 20, 1998 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSON