St George and the Dragon

Relief

ca.1450-1500 (made)

ca.1450-1500 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Decorated door jambs and lintels were a common feature of Renaissance architecture in Genoa. Reliefs depicting St George slaying the dragon were particularly popular in the city and were often adorned with coats of arms of the families who commissioned them for the entrances to their homes.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | St George and the Dragon (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Slate (pietra nera di promontoria), carved in relief |

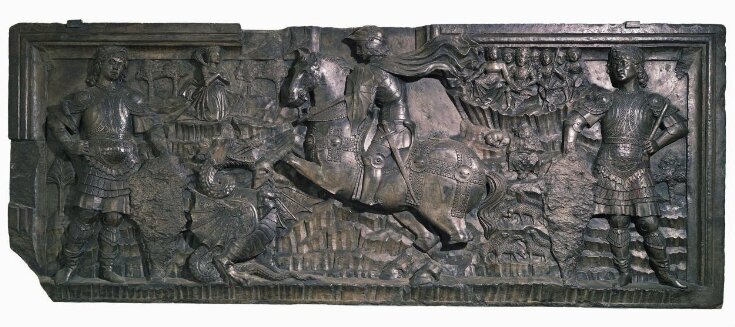

| Brief description | St. George and the Dragon, relief in slate (pietra nera di promontorio), in the style of Giovanni Gagini, Italy (Genoa), second half of 15th century |

| Physical description | St. George and the Dragon, relief in slate (pietra nera di promontoria). In the centre St. George, in left profile, spears the dragon, which appears in the foreground to the left. The Saint is fully armed and his cloak blows out behind him. To right and left are men in armour, each carrying a mace; both figures hold defaced shields. Behind, in the rocky landscape, are seen (left) the princess in prayer and (right) the king and queen with their court, and, beneath, a shepherd piping while his sheep graze below. The relief is recessed within a moulded border. Sections of the border have been chipped away in the upper left centre and on the left. The lower part of the Saint's spear is missing. Breaks in the lower part of the left front leg and both rear legs of the horse, and the maces carried by the armed figures at the sides. The shepherd is much abraded. A triangular section at the bottom has been broken and repaired. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | Purchased in Genoa for 22 lire.The relief is the type found above doorways in Genoa. Historical significance: This relief is very similar to one which has remained in situ over the doorway to the Palazzo Doria-Quartara in Genoa. (Pope-Hennessy, 389, cites Maclagan and Longhurst). The same elements are found in each, though the styles and compositions are different. Both contain St George shown in profile on a rearing horse while he slays a dragon whose wings are decorated with eyes. However, only the V&A dragon has a twisted neck. The backgrounds of each include a kneeling princess and a crowd of seated men around a king, who appear to be on a rocky outcropping, below which a bagpiper sits with sheep below him. Warriors holding shields flank St George in each relief, though the shields on the V&A relief have been effaced. This probably removed a family’s coat of arms, which originally would have advertised who lived within the house from which the relief was removed. The area above St George's head also seems to indicate that a monogram of Christ (as noted above, typical of such reliefs) was removed due to damage to the framing elements. Hasluck noted that the subject of St George for the reliefs seems to have its origins in the seal of the Bank of St George, the main bank of Genoa. He suggested that the reliefs might function as a type of triumphal monument for successful admirals, who were given the banner of St George before beginning their campaigns. (Hasluck, 1909-10, 171). Grosso, following a similar notion, commented that the flag of St George was carried on vessels and that victorious captains were awarded the honour of placing friezes with images of St George above the doors to their homes (Grosso, p.161). However, neither author cited any documentary evidence for their theories. |

| Historical context | Decorated door jambs and lintels were a common feature of Genoese architecture. As noted by R. Lightbown, their development was a result of the "…topography of the old city" in which tall houses were built on steep streets, thus leaving the doorway as the most visible area for display of wealth or family identification. (Lightbown, p.412). Rectangular carved lintels surmounted the doorways of palazzi, and the theme of St George killing the dragon was a popular choice for the lintel. Often a square projection with the monogram of Christ would be found above such lintels. The use of slate was typical in Genoa. It has high tensile strength and a high degree of water and fire resistance. These qualities, and its natural abundance in Liguria (the region of Genoa) made the city's preferred material for roof tiles, chimneys, doorways and floors. Giovanni Gaggini or his workshop may have carved this relief based on similarities with a relief over the doorway of Palazzo Quartara in Genoa (Pope-Hennessy, 389). There is some confusion surrounding that artist resulting from interpretations of documents from Genoa in the 1460s. Kruft, based on Cervetto, suggested that there were two men named Giovanni Gaggini, (alternatively spelled "Gagini") originally a Lombard family, working in Genoa during the same time. This was based on documents transcribed by Cervetto which seemingly referred to two sculptors, one named Giovanni Gaggini d'Andrea da Campione, who had a workshop in Genoa, and one called Giovanni Gaggini the son of Magister Beltrame, who came from Bissone (Cervetto, 137 and Kruft, 15). Bissone and Campione (today Campione d'Italia) are two towns very close to each other on the shore of Lake Lugano (in today's Switzerland). Until the 15th century, Bissone was under the rule of the Dukes of Milan, while Campione has remained Italian. Algeri suggested in 1977 that further research might reveal that Giovanni Gaggini da Campione and Giovanni Gaggini da Bissone were the same person, as a 1475 document published by both Alizeri and Cervetto made reference to a Giovanni da Beltrame from Campione who worked with Michele d'Aria for the Spinola family (doorway 222-1879 was a Spinola commission). She also noted that documents published by Cervetto regarding the location of the Gaggini shops locate them in the same area of Genoa and might provide further evidence for believing they are the same person. However, it does not appear that any further research on this branch of the Gaggini family has been done, and therefore identification remains speculative. Many doorways in Genoa had “sopraporte” with the theme of St George killing the dragon. The scene was favoured due to the saint’s popularity in that city. George was said to have been a soldier who was martyred in Lydda in Palestine. The story of George killing the dragon to save a princess from death is found in Jacopo de Voragine’s Golden Legend. There was a church dedicated to St George since at least the 8th century, but it seems the cult of St George grew in the years of the Crusades and increased contact between East and West. Genoa’s association with St George is most likely due to the city’s role as one of the great seafaring Republics of the early 1200s in Italy and its involvement in the Crusades and trade with the East. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Decorated door jambs and lintels were a common feature of Renaissance architecture in Genoa. Reliefs depicting St George slaying the dragon were particularly popular in the city and were often adorned with coats of arms of the families who commissioned them for the entrances to their homes. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 7255-1861 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 18, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest