Woven Silk

900-1100 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

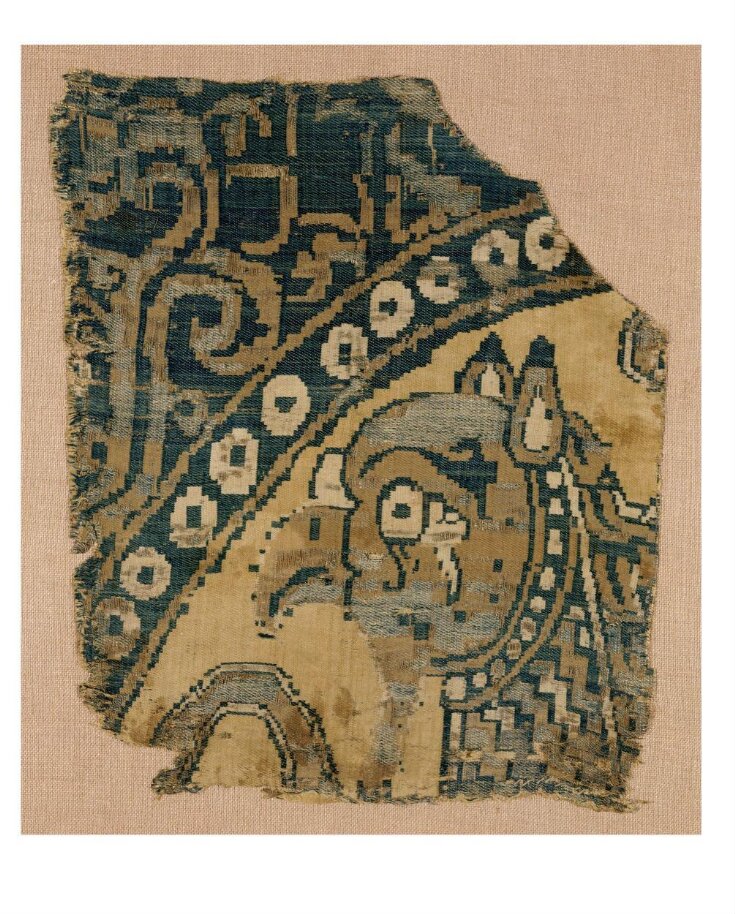

Unfortunately only part of the original scene on this fragmentary textile survives. The head of a griffin is shown with beak poised above part of an elephant's trunk. A section of the border of the roundel within which the scene was enclosed can be seen to the left of the creature. Animal combat scenes were often used by Byzantine artists to decorate textiles and sculptures. Fierce beasts and fantastic monsters including the griffin and sēnmurw, which were both versions of the same fabulous creature, were inherited from Sasanian art (a pre-Islamic Persian dynasty) and other earlier traditions. The complete design on the original textile has been worked out by means of checking other sources including a silk in West Germany and a marble relief on a parapet of an arch in St Mark's Basilica in Venice.

The legend of the beast of strength sufficient to carry an elephant, is found in several cultures and was reported by the great traveller Marco Polo in both an oriental and Indian context. The grand, large-scale pattern would originally have been repeated over the whole textile and it may have been produced in an imperial workshop in Constantinople.

The legend of the beast of strength sufficient to carry an elephant, is found in several cultures and was reported by the great traveller Marco Polo in both an oriental and Indian context. The grand, large-scale pattern would originally have been repeated over the whole textile and it may have been produced in an imperial workshop in Constantinople.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Woven silk |

| Brief description | Woven silk fragment with part of a scene of a griffin (gryphon) attacking an elephant; Byzantine; 999-1100; blue, yellow, gold and white |

| Physical description | Fragment of woven silk in a compound twill in dark blue, tan colour (probably once a brighter reddish hue), buff and white; part of a scene of a griffin (gryphon) attacking an elephant. The fragment shows the top left-hand portion of a large circle in which appears the griffin's head with a eagle's beak, prick ears, a goat's beard and a mane covering the neck; the curved tip of one wing is also visible behind the head and part of the elephant trunk below and to the left of the griffin's beak. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Styles | |

| Object history | Bought from Monsieur Stanislas Baron, rue Grange-Batelière 28, Paris for £30. (RP764-1893). Historical significance: Significant as a typical example of the silks with animals made in the east of Roman Empire in this period. |

| Historical context | Silk manufacturing 'Byzantine' silks were made in the east of the Roman Empire, the capital being Constantinople, long before the Latin West developed its own silk-weaving workshops. Raw silk was originally imported from China via Persia, but from the fifth century there are records of sericulture being practised in Byzantine Syria. Silk weaving was already established there by the 4th century and continued even after the fall in 1204 AD. This piece belongs to second phase of pre-thirteenth century weaving, a period after the Islamic conquests of Byzantine territory, including Egypt and Syria, when imperial production was centralised in Constantinople, and private workshops began to take root there also. In the city's guild regulations (The Book of the Prefect ) in the tenth century, five private silk guilds were represented. Only the imperial workshops were, however, allowed to make up certain shades of imperial purple, and certain types of tailored silk garments reserved for the imperial house. Use and trade In the tenth century, The Book of Ceremonies described the place of silk vestments and furnishings in the life of the court: imperial purple, golden, green, blue and red silks; plain silks and silks decorated with eagles, griffins, bulls and hornets or foliate motifs. This magnificence reached foreign nations via diplomatic channels and the sending of silks as gifts to foreign courts.The demand for these silks was great as the Latin West did not make silks of its own, and the Italians, the Bulgars and the Russians defended with military force the Byantine territories in exchange for silk-trade concessions and silken gifts. The Venetians and the German emperors had a particularly close relationship right through the eighth to twelfth centuries. Not surprisingly, most of the silks that survive from this period are to be found in ecclesiastical treasuries. Silks like this fragment may have been commissions or diplomatic gifts. If imported to the western Europe, they probably arrived through Venice, the only European city which had trading concessions with Byzantium. These concessions were consolidated in 1082 by an agreement which effectively made Venice a trading partner. Bibl: Anna Muthesius, 'Byzantine Silks' in 5000 Years of Textiles. London: British Museum Publications, 1995, pp. 75-80. Imagery The subject represents a version of the ancient legend of Oriental origin about a fabulous creature of prodigious strength (gryphs, rukh, garuda) which was capable of lifting an elephant. It is also related of the Indian garuda which could fly away with an elephant. The version imported in the book of Marco Polo indicated: the bird griffin...and it is so strong that it will seize an elephant in its talons and carry him high in the air.... The nature of the full design can be deduced from comparison with a larger fragment which has its pattern intact. It was found in the tomb of Count von Graisbach (d.1074) in St Waldburgh Abbey, Eichstadt, Germany. A similar design is found on an 11th century chasuble buried with an archbishop at Bremen Cathedral. It must originally have consisted of a series of large repeating roundels (each containing the two animals). Each repeat was at least 61 cm across, which suggests that these silks were woven on looms of unusual width, possibly the work of one of the Imperial workshops, possibly at Constantinople.Animal combat scenes, usually contained in roundels, were often used by Byzantine artists to decorate textiles and sculptures. Fierce beasts and fantastic monsters, including the griffin and sēnmurw, inherited from Sasanian art and earlier traditions, travelled on silks such as these to Western Europe. There they had an influence on the development of the Romanesque style. Collecting history On 14th July 1893, William Morris provided the Museum with a report on the collection of 50 textiles and an altar frontal offered by M. Baron and sent on approval on 22nd June (RP 32532/1893): 'This collection includes a great number of pieces of various dates and countries, ranging from the 10th to the 16th centuries, but the greater number of the 13th and 14th probably woven in Syria, Sicily, and some few at Lucca. They are all of high excellence as works of art; the designs being very inventive, and of great beauty and thoroughly adapted to the material in which they are executed. Many of the pieces are large, and exchibit several repeats of the pattern, which I consider a great advantage for specimens intended for exhibition in a museum; many also are in exceptionally good condition, the colours being so little faded that the effect produced by the ancient weaver is still clearly seen. The collection seems to me to be very valuable for purposes of study and I should recommend it for acquisition. The price at which they are offered does not seem to be extravagant considering their quality.' (RP64437/1893) The first evidence in MA/1/8494 of M. Baron sending objects on approval to the Museum dates to January 1889 and he continued to send items until 1901. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Unfortunately only part of the original scene on this fragmentary textile survives. The head of a griffin is shown with beak poised above part of an elephant's trunk. A section of the border of the roundel within which the scene was enclosed can be seen to the left of the creature. Animal combat scenes were often used by Byzantine artists to decorate textiles and sculptures. Fierce beasts and fantastic monsters including the griffin and sēnmurw, which were both versions of the same fabulous creature, were inherited from Sasanian art (a pre-Islamic Persian dynasty) and other earlier traditions. The complete design on the original textile has been worked out by means of checking other sources including a silk in West Germany and a marble relief on a parapet of an arch in St Mark's Basilica in Venice. The legend of the beast of strength sufficient to carry an elephant, is found in several cultures and was reported by the great traveller Marco Polo in both an oriental and Indian context. The grand, large-scale pattern would originally have been repeated over the whole textile and it may have been produced in an imperial workshop in Constantinople. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 764-1893 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 17, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest