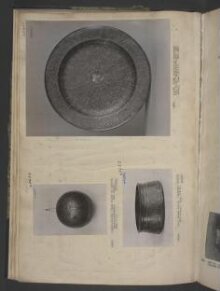

Dish

1500-1550 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

The brass dish dates from the mid-16th century. It is damascened, a technique which involved decorating engraved iron, brass or steel with gold or silver wire. The technique originated in Damascus and was mostly used by Islamic craftsmen.

This dish was made for an unidentified Italian family, whose coat-of-arms decorates the centre. The dish is decorated in the 'Veneto-Saracenic' style with motifs and patterns inspired by Islamic art forms popular in Venice during the 15th and 16th centuries. Much so-called "Veneto-Saracenic" metalwork was actually produced in Mamluk lands for export to Europe. This example, though, may be the product of a Venetian craftsman working in a Mamluk-inspired idiom: the arabesque ornament is less abstract and more regulated than on traditional Mamluk wares.

In Venice, the production of brass dishes and vessels flourished in the first half of the 16th century. They were very elaborately decorated but not with traditional European linear ornamentation. Venice, during this period, traded and fought extensively with the Turkish and Arab empires which bordered the Mediterranean basin. Thus Venetian merchants brought back to the city Near Eastern goods that had an immediate influence on local design, and eventually the rest of Europe.

Decoration on Venetian brass was more extensive, often covering the entire surface of an object. The arabesque pattern, base on a stylised plant with a winding stem, was studied and copied by contemporary Italian artists. By the middle of the 16th century, the arabesque as a form of ornament was beginning to influence craftsmen all over Europe, and became incorporated into the development of European ornamental design, until the decline of the Rococo in the late 18th century.

This dish was made for an unidentified Italian family, whose coat-of-arms decorates the centre. The dish is decorated in the 'Veneto-Saracenic' style with motifs and patterns inspired by Islamic art forms popular in Venice during the 15th and 16th centuries. Much so-called "Veneto-Saracenic" metalwork was actually produced in Mamluk lands for export to Europe. This example, though, may be the product of a Venetian craftsman working in a Mamluk-inspired idiom: the arabesque ornament is less abstract and more regulated than on traditional Mamluk wares.

In Venice, the production of brass dishes and vessels flourished in the first half of the 16th century. They were very elaborately decorated but not with traditional European linear ornamentation. Venice, during this period, traded and fought extensively with the Turkish and Arab empires which bordered the Mediterranean basin. Thus Venetian merchants brought back to the city Near Eastern goods that had an immediate influence on local design, and eventually the rest of Europe.

Decoration on Venetian brass was more extensive, often covering the entire surface of an object. The arabesque pattern, base on a stylised plant with a winding stem, was studied and copied by contemporary Italian artists. By the middle of the 16th century, the arabesque as a form of ornament was beginning to influence craftsmen all over Europe, and became incorporated into the development of European ornamental design, until the decline of the Rococo in the late 18th century.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Brass, engraved and overlaid with silver |

| Brief description | Dish of copper alloy with densely engraved decoration of small-scale arabesques within a continuous pattern of larger arabesques, knotwork and compartments with scalloped outlines worked in silver wire, and a coat of arms in silver in the central roundel, probably Damascus, Syria, 1500-1550 |

| Physical description | Dish of copper alloy, flat, with a broad everted rim, decorated partly in silver in a late Mamluk export style, and probably produced in Damascus, Syria, about 1500-1550 for the Italian market. There is a continuous linear pattern of arabesque scrollwork (tendrils bearing stylized leaves seen side-on, called "half-palmettes"), small knots, and compartments with scalloped outlines, all worked in silver wire. The spaces within this linear pattern in silver are engraved all over, mostly with arabesque scrollwork on a much smaller scale. The central roundel contains an unidentified European coat of arms, overlaid in silver and engraved. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | Coat of Arms in central boss: unidentified |

| Object history | The provenance of this dish before the 19th century is not known. It was bought by the Museum from the Bernal Collection in 1855. This was an enormous collection of metalwork, glass, ceramics and miniatures belonging to Ralph Bernal, a lawyer and MP. The sale by Christie, Manson and Woods took 32 days during which 4294 lots fetched nearly £71,000. The Museum bought 730 lots including this dish for which it paid £43.1s |

| Historical context | The dish is damascened, a technique which involved decorating engraved iron, brass or steel with gold or silver wire. The technique originated in Damascus and was mostly used by Islamic craftsmen. This dish was made for an unidentified Italian family, whose coat-of-arms decorates the centre. The dish is decorated in the 'Veneto-Saracenic' style with motifs and patterns inspired by Islamic art forms popular in Venice during the 15th and 16th centuries. Much so-called "Veneto-Saracenic" metalwork was actually produced in Mamluk lands for export to Europe. This example, though, may be the product of a Venetian craftsman working in a Mamluk-inspired idiom, as can be seen in the highly Europeanizing arabesque ornament. In Venice, the production of brass dishes and vessels flourished in the first half of the 16th century. They were very elaborately decorated but not with traditional European linear ornamentation. Venice, during this period, traded and fought extensively with the Turkish and Arab empires which bordered the Mediterranean basin. Thus Venetian merchants brought back to the city Near Eastern goods that had an immediate influence on local design, and eventually the rest of Europe. Decoration on Venetian brass was more extensive, often covering the entire surface of an object. The arabesque pattern, base on a stylised plant with a winding stem, was studied and copied by contemporary Italian artists. By the middle of the 16th century, the arabesque as a form of ornament was beginning to influence craftsmen all over Europe, and became incorporated into the development of European ornamental design, until the decline of the Rococo in the late 18th century. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | The brass dish dates from the mid-16th century. It is damascened, a technique which involved decorating engraved iron, brass or steel with gold or silver wire. The technique originated in Damascus and was mostly used by Islamic craftsmen. This dish was made for an unidentified Italian family, whose coat-of-arms decorates the centre. The dish is decorated in the 'Veneto-Saracenic' style with motifs and patterns inspired by Islamic art forms popular in Venice during the 15th and 16th centuries. Much so-called "Veneto-Saracenic" metalwork was actually produced in Mamluk lands for export to Europe. This example, though, may be the product of a Venetian craftsman working in a Mamluk-inspired idiom: the arabesque ornament is less abstract and more regulated than on traditional Mamluk wares. In Venice, the production of brass dishes and vessels flourished in the first half of the 16th century. They were very elaborately decorated but not with traditional European linear ornamentation. Venice, during this period, traded and fought extensively with the Turkish and Arab empires which bordered the Mediterranean basin. Thus Venetian merchants brought back to the city Near Eastern goods that had an immediate influence on local design, and eventually the rest of Europe. Decoration on Venetian brass was more extensive, often covering the entire surface of an object. The arabesque pattern, base on a stylised plant with a winding stem, was studied and copied by contemporary Italian artists. By the middle of the 16th century, the arabesque as a form of ornament was beginning to influence craftsmen all over Europe, and became incorporated into the development of European ornamental design, until the decline of the Rococo in the late 18th century. |

| Associated objects |

|

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 2061-1855 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 16, 2004 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest