Great Bed of Ware

Bed

1590-1600 (made)

1590-1600 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Object Type

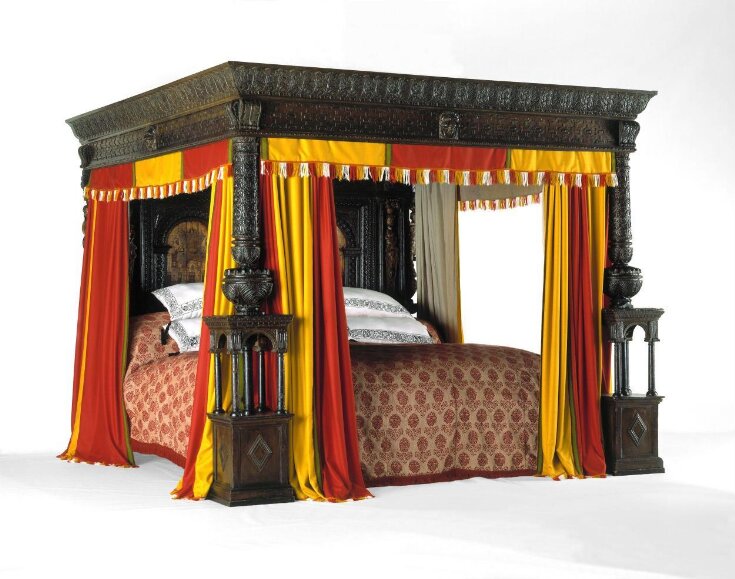

This bed is in the typical style of carved wooden beds of the 1590s but it is remarkable for its large size. It is over 326 centimetres wide. The height was slightly reduced in the 19th century. The human figures carved on the headboard would originally have been brightly painted.

Places

The bed was probably made as a curiosity to attract customers to one of the inns at Ware, Hertfordshire. Ware is 22 miles from London, then a day's journey on horseback or by coach. The town had many inns in the 1590s.

Historical Associations

The bed has been famous since it was made. William Shakespeare mentioned it in his play Twelfth Night, first performed in 1601. The contemporary playwright Ben Jonson called it 'the great bed at Ware' in a play in 1609. Visitors often carved their initials on the bed or applied red wax seals, which are still visible on the bedposts and headboard today.

This bed is in the typical style of carved wooden beds of the 1590s but it is remarkable for its large size. It is over 326 centimetres wide. The height was slightly reduced in the 19th century. The human figures carved on the headboard would originally have been brightly painted.

Places

The bed was probably made as a curiosity to attract customers to one of the inns at Ware, Hertfordshire. Ware is 22 miles from London, then a day's journey on horseback or by coach. The town had many inns in the 1590s.

Historical Associations

The bed has been famous since it was made. William Shakespeare mentioned it in his play Twelfth Night, first performed in 1601. The contemporary playwright Ben Jonson called it 'the great bed at Ware' in a play in 1609. Visitors often carved their initials on the bed or applied red wax seals, which are still visible on the bedposts and headboard today.

Delve deeper

Discover more about this object

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 28 parts. (Some alternative part names are also shown below)

|

| Title | Great Bed of Ware (popular title) |

| Materials and techniques | Oak, carved and originally painted, with panels of marquetry |

| Brief description | The Great Bed of Ware, oak, carved, inlaid and painted. British, 1590-1600. |

| Physical description | Bed of oak, with carved posts, headboard and tester. The headboard is inlaid with two marquetry panels within arched frames, and is divided vertically by three carved figures, two male and one female. On each side of the headboard is a figure of a satyr. The woodwork shows traces of paint. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Production type | Unique |

| Credit line | Purchased with Art Fund support |

| Object history | Bought for £4000 (with a contribution of £2000 from the National Art Collections Fund) from Messrs. Frank Partridge & Sons, 26 King St., London SW1; RF 31/7428 Lent 2012–13 to the special loan exhibition 'The Great Bed in Ware' at Ware Museum in Hertfordshire, where it was seen in a specially designed building by over 34,000 visitors. A replica of one of the footposts was commissioned by Ware Museum and displayed alongside the bed. A souvenir pamphlet was produced by the Ware Museum Trust (2013). The exhibtion was supported by The Heritage Lottery Fund, Ware Town Council, Ware Museum Trustees and donations from local people and institutions. History The origins of the bed are unclear. It was probably made as a curiosity to attract customers to stay at one of the inns at Ware, which was then a day's journey from London on horseback or by coach (22 miles). As a staging post, Ware had many inns by the end of the 16th century, and had the additional advantage of a connection to the Thames by the river Lea. It is unlikely, as sometimes suggested, that the bed was made for Ware Park, a nearby large house. The earliest reference to the bed is in 1596, when the bed must have been in an inn, as a German visitor, Prince Ludwig of Anhalt Kohten, mentioned the bed in his diary, the "Poetical Itinerary". The bed is referred to in Shakespeare's Twelfth Night, first performed in 1601, and continued to be mentioned in plays, bawdy tales and by travellers (see references). It has been known as `The Great Bed of Ware' since at least 1609 when it was mentioned in a play by Ben Jonson. It must have been widely known in 1666 to have been referred to in a poem about the great fire of London (London Undone; or, A Reflection upon the Late Disasterous Fire; London, Printed by E.C. for H. Eversden, and H. Brome, 1666): "But then (alas!) men had no time to talk,/ No more but so, Take up your Bed and walk,/ Into the Fields on that bleak dew-dropt Grass,/ Where the Earth Bed, and Heaven its Teaster was./ Infants and aged quarter'd row by row,/ Never Quarters had More-fields then now./ The Miscellany made in every square,/ The Counterfeit of the Great Bed of Ware...." The size of the bed was frequently exaggerated; a writer in 1732 claimed it could 'hold twenty couple' (Thornton, 1976). Its importance has also been exaggerated: at one time it was thought that the bed might have been made for royal use, and the date 1463 which was painted on the headboard, now faded, reflects the tradition that it was made for King Edward IV (Thornton, 1976). The bed featured in a London pantomime in 1839, which gave rise to the story that it was made by a character called 'Jonas Fosbrooke'. Visitors who stayed at the inns often carved their initials in the bed and applied red wax seals, still visible on the bedposts and headboard. In the 19th century the bed became known among antiquarians, including Henry Shaw, who illustrated it in Specimens of Ancient Furniture in 1836. It passed through the ownership of several inns, notably The Saracen's Head where it stayed from 1765 to 1870 (Thornton, 1976, when it was bought by the Rye House Hotel in nearby Hoddesdon. Rye House hotel had fifty acres of gardens which were developed as a tourist destination, including a fairground. While at Rye House parts of the bed displayed in a building especially constructed in the garden. Parts of the bed were restored or replaced, notably the frieze to the tester. Photographs show a set of antlers attached to the top of the bed, associated with a custom whereby a cautionary oath was proclaimed over the visitor by the innkeeper for a fee, known as the 'swearing of the horns'. The Museum has a set of photographs of Rye House taken in about 1900 (on the Departmental catalogue), and a fragment of the material displayed either on the bed or in the same room at that time, of 1690s crewel-work. The bed was sold with the hotel to the Cannon Brewery in 1927, who wished to dispose of the bed. In 1931 it was sold for £4000, then a very large sum, to Frank Partridge and Sons Ltd, the London antique dealers, who agreed to sell it on at cost price to the V&A after exhibiting it themselves. The V&A acquired it principally for its historical and litererary status and to prevent it being sold abroad. The acquisition papers include an account of a visit to Rye House in about 1910 by Mr Clifford Smith, a curator in the Furniture Department, and a postcard, hand-bill and leaflet about Rye House collected at that time. The bed today shows many signs of alteration, particularly to the columns, which have been cut down at some time and are missing their capitals. The frieze around the top is certainly a replacement, as the 1910 postcard 1910 shows a previous, much damaged frieze. The underside of the tester is probably a replacement, as are the panelled lower sections to the legs. Analysis of the paintwork shows that some original paint survives on the carved figures and that the headboard was overpainted in dark green, possibly in the 18th century, afterwards removed. At Rye House the bed was displayed with boards attached to the sides and end of the bedframe, possibly added at the time. The boards have carved graffiti but marks show that they were re-used, possibly from school desks. A copy of the Great Bed of Ware was offered for sale by Unique Auctions, Lincoln, in their sale of 6/7 April 2024, illustrated in Antiques Trade Gazette 6 April 2024, p. 21. That bed was narrower, clearly made to standard bed size, probably in the early 20th century. Historical significance: One of the best-known pieces of English furniture, this bed has been famous since it was made, for its unusually large size; no other beds from the period on this scale are known. The woodwork is profusely carved with anglicised Renaissance patterns, acanthus leaves and strapwork. The three human figures vertically dividing the headboard, two male and one female, carry baskets of fruit on their heads symbolising fertility. At each side edge of the headboard are carved satyrs with hoofed feet, symbolising drink and lust. The human figures carved on the headboard and the underside of the tester, or wooden canopy, show traces of paint and would originally have been brightly coloured, as was much Elizabethan furniture. The two marquetry panels in the headboard showing architectural scenes and swans are typical of the work introduced by German craftsmen settling in London in the late 16th century, and are strongly influenced by the designs of Hans Vredeman de Vries (1527-1604), the Dutch artist. A precise source has not so far been identified. Swans can be seen swimming in the foreground, perhaps a reference to the River Lea running through the town of Ware, which was famous for its swans. However, swans are also found on other German furniture of around the same date. |

| Historical context | No other Elizabethan beds on this scale are known. However, in form and decoration it epitomises the flamboyantly carved and painted beds of the late Elizabethan period. Hangings would originally have been suspended from the tester on three sides to provide privacy and warmth, with valances on the tester and below the bedframe to hide the legs. The bedding would have been substantial on a bed of this quality. Bedcords would have been threaded through the holes in the bedstock to support the mattresses. Specially designed tighteners were used to keep these taut, giving rise to the expression 'sleep tight'. A woven or plaited rush bedmat would have been placed over the cords, supporting several layers of mattresses, possibly flock below and feather above. On lesser quality beds the bottom mattress would have of straw. The sheets and pillow covers would have been linen, with woollen blankets, and a decorative coverlet. With such a number of elements to the bedding, which would have risen up to the decorative section of the headboard (hence the lower section is plain), there was a danger that the bedclothes might slip off. Wooden poles or 'bed-staves' were used, pushed inside the lower frame, or into holes in the frame, to hold it all on. They are commonly mentioned in connection with beds in 16th and 17th century inventories, but no surviving examples of bedstaves are known to the author in England, although some survive in Sweden. The bed was acquired with boards attached to the sides of the bedframe. These were often a feature of Tudor beds and probably served both as somewhere to sit, as the bedclothes were so high, and as a step up onto the bed. The coverlet would not have covered the boards. RE-HANGING THE GREAT BED OF WARE Notes collated by Sarah Medlam (Furniture Department) at the time of redisplay of the bed, 2001 History of the Bed In some ways we know a lot about the Great Bed of Ware because it has been mentioned in various literary texts since 1600, when Shakespeare first mentioned it in Twelfth Night, writing of a sheet ‘big enough for the bed of Ware’. Since that time it has been documented in various literary texts and in travellers’ accounts. In 1596 Prince Ludwig of Anhalt-Köhten recorded a bed at Ware, in which ‘four couples might comfortably lie side by side’. In 1610 Prince Ludwig Friedrich of Württemberg slept at Ware in a bed ‘eight feet wide’. At this time the bed was at The White Hart in the town, but for the earlier visit it may have been at The Crown. In 1706, apparently, the bed moved to The George. After that it was (perhaps for a second time) at The Crown, then back to The Saracen’s Head in 1765, where it stayed until 1870. A local hotel owner with antiquarian leanings bought it at that time and installed it in The Rye House Hotel at nearby Hoddesdon, in a special building in the garden, where it was shown with other antiquities. People flocked to see it, with excursions from London being offered by the railway. Charles Dickens is said to have tried to buy the bed. Sixty years later the bed was once more for sale. The Museum bought it for £4000, with the help of the National Art Collections Fund. But there is much more that we do not know. No explanation has been unearthed as to why it is so large. If it was originally made for an inn (as seems most likely) it is possible that it was simply made in an exaggerated manner to drum up trade. This it certainly did and it is still a popular draw to visitors to the Museum, our single most asked-for exhibit. Another area of mystery concerns its hangings. In the 19th century its antiquarian owner draped it with panels of 17th century crewel work embroidery. This was an enthusiastic effort to make it look ‘old’ but it could not have been what was on the bed when it started its life. The Woodwork of the Bed The immense carved posts with their complex carved patterns would have been in the height of fashion in the 1590s. So would the inlaid patterns visible on the headboard. When the bed was new these would have been very different in colouring, showing a strong contrast between the black and white areas of the inlay. This kind of inlay, particularly those panels showing imagined buildings, was a speciality of Southwark in London where it was made by Protestant German joiners who had settled there and established workshops specialising in this work. Some kind of customisation may have been intended because some of the panels show swans and swans were a symbol connected with the town of Ware. The carved figures on the headboard of the bed are large-scale and intended to have an immediate impact. When new, this impact would have been even stronger, when the coloured paintwork on the figures would have been bright, even gaudy by twenty-first century standards. The bed has been altered during more than one period. An engraving published in the 19th century shows that the bed had a quite different frieze round the top at that date. Three ‘settles’ or planks exist, which were once attached to the sides of the bed, but we have not replaced them because they are not thought to be original All this alteration can be seen as damaging the bed and making it less authentic but as with any relic, whether of a hero or a saint, there is a tradition of repairing and beautifying. This is a natural part of venerating something and wanting it to continue and, perhaps, to be ‘improved’. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries the bed continued to appear in literature; the poet Lord Byron mentioned it. Less grandly, in 1839 a pantomime called The Great Bed of Ware was produced at the Theatre Royal, London. At this period it also began to attract the attention of antiquarians and was mentioned in serious historical publications, including Henry Shaw’s, Specimens of Ancient Furniture, which illustrated the bed in 1836. The status of the bed as a rarity to be visited and as a relic can be seen in the amount of grafitti that has been carved into it, including many sets of initials and several dates. Visitors to the bed have also commemorated themselves by setting their seals in red wax on various parts of the bed. The Evidence for the New Hangings No evidence exists of how this particular bed might have been curtained when it was new. The best information we have comes from inventories of the years round 1600 and an assessment of what these have to say about beds of this sort of quality. Many such inventories exist and it is possible to narrow research by choosing only inventories of houses in a particular social range (some even exist for inns) and for particular geographic areas. For instance, it was a numerical analysis of inventories from southern England that showed that red and yellow was the most popular combination. Some judgements have had to be made. We do not know, for instance, how ‘special’ this bed was, so we have assumed high quality hangings and bedding but not anything that goes beyond the kind of item listed in inventories of inns and ‘middling’ houses. This was certainly not a bed for royalty or the nobility, but there would have been no point in bragging about the large scale of the frame and then hanging it in drab or poor quality fabrics. Beds were highly important items of furniture in houses and their hangings frequently cost more than the frames. For this project the Museum was advised by Dr Charles Kightly of York. Dr Kightly is a scholar specialising in the investigation and re-creation of furnishings of the 17th century and earlier. Elements for the re-hanging were made all over Britain. What Was Made Ironwork No old mechanism for hanging curtains existed on the bed except two hooks. New hanging rods have been made by a blacksmith with hand-forged iron rings to hang the curtains. The valances hang from lighter rods. Blacksmithing is a craft that has continued to use established and traditional techniques of working iron. The blacksmith that made these rods worked in Flamborough, East Yorkshire. They were carefully designed to be attached without making new holes in the old woodwork and measurements had to be taken very carefully as no adjustment was possible once they were made. Roping The first layer of the bed base was hemp rope. The original holes for roping the bed have been used and the rope made in Hawes, North Yorkshire. Bedmats Sixteenth century households laid bedmats on the ropes to provide a firm base for the mattresses that otherwise might bulge through the wide spaces between the roping. Bedmats were made of plaited rushes. The new mats (two to cover such a large bed) were made to the traditional pattern in Aldeby, Suffolk. Mattresses Three mattresses have been provided. The originals would have been filled with unspun woollen flocks (lowest), feathers (middle) and down (topmost). In the reconstruction these have been filled with inert polyester filling because of the danger of infestation by insects (which would certainly relish the natural oils in wool or feather and would move on to older and rarer textiles in the galleries in due course). This modern filling for the mattresses is the only departure from traditional materials used on the bed. One mattress is covered in striped ticking of a period pattern. Two are covered in plain canvas. Both kinds of fabric appear in 16th- and 17th-century inventories and patterns for the striped ticking have been taken from contemporary illustrations that show beds. All the linens for the project have been woven in Montrose, Scotland. Who provided the inert fillings we don’t know. Sheets Two plain linen sheets were woven in Montrose to the narrow width (21”) that was standard. The widths were then sewn together. All hidden stitching on this project was done by machine for reasons of speed and cost, but hems and visible areas were stitched by hand. The making up of all the bedclothes and hangings was done in a workshop in Leominster, Herefordshire. Bolster, pillows and pillowcases The bed has a bolster, covered in striped linen ticking and filled with inert material. Eight pillows have been made. These are of striped ticking, filled (like the mattresses) with inert, modern materials. Of these, four have plain linen cases (the whiteness of linen was a matter of pride to a 16th century housewife). Four have blackwork embroidery to decorate the cases or ‘pillowberes’– two with a design copying a pillowcase in the Museum’s collection and two using 16th-century design drawings from a manuscript to compose a new pattern in the way that would have been done in the 16th century. All this work has been undertaken by the Leominster workshop. Blankets The bed has two woollen blankets, woven to a narrow width (21”) and seamed. The blankets have a twill weave (showing a diagonal patterning in the weave). At the top end they show woven blue stripes. This was traditional in the 16th century and has remained traditional as a decoration for blankets until present times. The blankets were woven in Selkirk, Scotland. Quilt Sixteenth-century beds were often provided with a quilt as a major showpiece of textile. The Great Bed of Ware’s is in ‘shot sarcenet’, a taffeta type of silk with the warp and weft in different colours so that it shows different colours as the light falls from different directions. This kind of silk is often mentioned in inventories for beds in the 16th-and 17th-centuries. The silk for this quilt was woven in Castle Headingham, Suffolk. The pattern for the embroidery of the quilt was taken from a 16th-century quilt in the Museum’s collection. The two colours of the silk are ‘carnation and green’ (pink and green), one of the most recorded colour combinations. The silk was dyed with traditional vegetable-based dyes. The wadding should be woollen flocks but, as with other items on the bed, we have used inert modern fillings. Counterpane The counterpane of a bed was always an area for display of luxury. The counterpane for the Great Bed of Ware is in a patterned fabric, woven in wool with linen and gold thread. This has been re-woven, in Montrose, Scotland, following the pattern of a 16th-century textile in the V&A’s collection. We do not know whether the V&A fragment was made in Britain or on the Continent, but we do know that it is similar to fabrics that were woven in this country. Inventories of the time list ‘dornix’ for counterpanes. We know that dornix was a fabric of mixed fibres, often wool and linen and sometimes with gold thread added, so it is likely that what is here is the fabric our ancestors knew as ‘dornix’. The new fabric is woven in brick red with natural-coloured, unbleached linen and an alternate weft in gold thread. The pattern shows a large flower-head. The dyeing of all the red wool for this project was undertaken on the Isle of Skye in Scotland, using dyes based on the plant madder. The cloth is reversible and is not lined. This is very important to the Museum as it leaves less space for insects to settle and makes the cleaning and housekeeping of a woollen textile much easier. Hangings The curtains and valances of the bed are in bold stripes of red and yellow say, a twill-woven wool. Say was very frequently mentioned in inventories of the period for bed hangings. They are ‘paned’ i.e. made of alternate narrow loom widths of red and yellow. This was the most popular colour combination listed in inventories of houses in the southern counties of England. The say was woven in Selkirk, the red wool dyed first in the Isle of Skye, the yellow wool dyed in Rochdale, Lancashire, using dye from the plant weld, cut in Pocklington, North Yorkshire. The curtains are fringed and decorated with woollen braiding woven in Malton, North Yorkshire. Bed staves These are long wooden staffs that were used to keep the bedclothes in place to flatten the centre of the bed when it was made each day. A reproduction set has been made for showing with the bed. Bed-cord tighteners These are small wooden levers used to tighten each crossing of rope as it is threaded through. The rope is a continuous length. Over time the rope would sag and would need to be re-stretched. The bed-cord tighteners were made in Presteign, Wales. Handling Collection To cater for the temptation to touch that naturally afflicts visitors, we have provided handling samples of all the materials used in the bed, with a diagram of the various layers. For the handling collection, wool and feathers are used for the ‘mini mattresses’ so that visitors can feel what 16th-century sleepers might have felt. The ‘Great Bed of Ware’ Makers & Suppliers (2000) Consultant- Charles Kightly, 50 Huntingdon Road, York YO31 8RE For this project the Museum was advised by Dr Charles Kightly of York. Dr Kightly is a scholar specialising in the investigation and re-creation of furnishings of the 17th century and earlier. It is his work on inventories that has been used as the basis for our re-creation. Bedcords - Outhwaite Ropemakers, Town Head, Hawes , North Yorkshire The first layer of the bed was hemp rope. The original holes for roping the bed have been used The bedcords are 8mm in diameter being dictated by the size of the holes of the bedstock. A total of 70m was made by Norman Chapman using methods unchanged since 1600, on the ropewalk of Messrs. Outhwaite, one of the few traditional ropewalks still in use. Bedcord Tighteners - John Nethercott and Co, Upper House, Discoed, Presteigne, Powys. LD8 2HG The 4 tighteners were made in oak, using gouge chisel and drawknife, by Paul Northwood of Llangunllo, in the workshops of John Nethercott and Co. Bed staves- John Nethercott and Co, Upper House, Discoed, Presteigne, Powys. LD8 2HG The 6 bedstaves of turned oak, uncoloured but finished in turpentine and walnut oil were made by Meurig Griffiths of John Nethercott and Co. Ironwork - John Hill, Daneswood Forge, Danes Dyke, Flamborough, East Yorkshire, YO1S 1AA No old mechanism for hanging curtains existed on the bed except two hooks. New hanging rods have been made by a blacksmith with hand-forged iron rings to hang the curtains. The valances hang from lighter rods. They were carefully designed to be attached without making new holes in the old woodwork and measurements had to be taken very carefully as no adjustment was possible once they were made. Bedmats - Waveney Rush Industry Ltd, The Old Maltings, Cladercott Road, Oulton Broad, Lowestoft, Suffolk, NR32 3PH Bedmats were made of plaited rushes. The new mats (two to cover such a large bed) were hand-made from plaited East Anglian rush, plaited in threes to form narrow strips, sewn together with hemp twine and bound in woven rush at both ends. Makers included Angela Butcher, Claire Pettifer, Julie Pavitt and Abigail West. Mattresses & Bolster The bed has 3 mattresses: a (nominal) flockbed, a (nominal) featherbed and a (nominal) downbed with matching bolster. All are filled with inert polyester fibre and are covered in undyed hand-woven linen canvas of a traditional type, approximating to ‘dowle’ or ‘locram’. The downbed and bolster are covered in hand-woven ticking with a woven-in indigo-dyed blue stripe. The covering linen textiles of the mattresses and bolster were supplied by Angus Handloom Weavers, Scotland. They were made and filled by Wendy Rulton and her assistants at Leominster. Pillows All textiles for the pillows were supplied by Angus Handloom Weavers. Scotland and all the making-up was done by Wendy Rulton and assistants, Leominster. Embroidery The black work was carried out over a period of 4 months by Wendy Rulton and Ann Harris (the Trevelyan designs) and Sheila Powles and Jenny Vale. Sheets Two plain hand-woven linen sheets each made up of 3 loom widths pieced and hemmed. Fabric supplied by Angus Handloom Weavers, Scotland. All hems and visible areas of stitching were stitched by hand. The making-up of all the bedclothes and hangings was done by Wendy Rulton’s team in Leominster. Thread for embroidery & tassels The silk thread for the blackwork embroidery and the tassels on the pillows was dyed using logwood with an iron mordant, by Debra Crum who also made the tassels. Blankets The pair of blankets were made up of 3 loom widths, stitched together. The thick twilled white blanketing material has 2 indigo-dyed list stripes at top and bottom edges. The textile was handwoven and made up by Angus Handloom Weavers. The indigo yarn was dyed by Eva Lambert, Isle of Skye Quilt The facing silk was provided by Humphries Weaving Co, Devere Mills, Castle Hedingham, Suffolk. They also dyed the yarns pink & green. The quilt is backed with green linen from Angus Handloom Weavers and stuffed with inert polyester fibre (for conservation reasons). The design of the couched-work borders is copied directly from a 16th-century quilt in the V&A collection (4648-1859). The green couching thread was dyed by Debra Crum of Rhewl, Denbigshire and the other threads by Humphries Weaving Company. The quilt was made up and embroidered by Wendy Rulton, assisted by Jenny Vale, Ann Harris and Sheila Powles, Leominster. Coverlet The textile was woven by Ian Dale of Brechin, Scotland on a specially made ‘dornix’ jacquard loom, using lightly bleach linen thread, wool and flat 18-carat gold strip. The coverlet was assembled by Wendy Rulton an assistants, Leominster. The wool yarn used for main textile and fringe was dyed by Eva Lambert, Isle of Skye, using madder and brazil wood in an alum mordant. The fringe around the coverlet was tablet woven by Catherine Stallybrass and assistants, Norton-on-Derwent, East Yorkshire Curtains & Valences The cloth was woven by Angus Handloom Weavers, Scotland. The yarns were vegetable dyed by Eva Lambert, Isle of Skye (the red using madder with alum mordant) and Simon Cooper of Rochdale, Lancashire (the yellows using weld with alum; the greens for the braid, using weld and wood; and the browns for the braid, using tanbark with various mordants). Linings were handwoven by Angus Handloom Weavers, Scotland Braids and fringes were table-woven by Catherine Stallybrass and daughters, Norton-on-Derwent Curtains and valences were made up by Wendy Rulton and assistants, Leominster. Summary Bedcords Norman Chapman, Outhwaite Ropemakers, Town Head, Hawes, North Yorkshire Bedcord Tighteners Paul Northwood of Llangunllo for John Nethercott and Co, Upper House, Discoed, Presteigne, Powys. LD8 2HG Bedmats Sammy Crisp, Angela Butcher, Claire Pettifer, Julie Pavitt and Abigail West of Waveney Rush Industry Ltd, Oulton Broad Lowestoft, Suffolk, NR32 3PH Bedstaves Meurig Griffiths for John Nethercott and Co, Upper House, Discoed, Presteigne, Powys. LD8 2HG Ironwork John Hill, Daneswood Forge, Danes Dyke, Flamborough, East Yorkshire, YO1S 1AA Fabric for bolster, pillows and mattresses, sheets, blankets , curtains & valences supplied by Angus Handloom Weavers, House of Dun, by Montrose Angus, Scotland, DD10 9LQ Making-up of textiles Wendy Rulton , Sheila Powles, Ann Harris & Jenny Vale, Manaton, Pinsley Road, Leominster, Herefordshire, HR6 8NW Thread dying for embroidery and tassels and tassel making Debra Crum, Maesgwyn Rhewl, Ruthin, Denbigshire, Wales, LL15 1UL Quilt Silk supplied by Humphries Weaving Co, De Vere Mill, Castle Headingham. Halstead, Essex, CO9 3HA Linen backing from Angus Handloom Weavers, House of Dun, by Montrose Angus, Scotland, DD10 9LQ Green couching thread was dyed by Debra Crum of Rhewl, Denbigshire The quilt was made up and embroidered by Wendy Rulton, assisted by Jenny Vale, Ann Harris and Sheila Powles, Manaton, Pinsley Road, Leominster, Herefordshire, HR6 8NW Textile for coverlet woven by Ian Dale, Angus Handloom Weavers, House of Dun, by Montrose Angus, Scotland, DD10 9LQ Fringes and braids on coverlet made by Catherine Stallybrass, 54 Welham Road, Norton-on-Derwent, Malton East Yorkshire, YO17 9DP Wool yarn of coverlet and coverlet fringe dyed by Eva Lambert, Waternish, Isle of Skye, IV55 8GL Simon Cooper , Westbank, 410 Shawclough Road, Rochdale, Lancashire, 0L12 7HR Curtains & valence linings handwoven by Angus Handloom Weavers, House of Dun, by Montrose Angus, Scotland, DD10 9LQ Curtains & valence braids and fringes tablet-woven by Catherine Stallybrass and daughters, Malton, East Yorkshire, YO17 9DP Curtains and valences made up by Wendy Rulton and assistants, Manaton, Pinsley Road, Leominster, Herefordshire, HR6 8NW |

| Production | The marquetry decoration is influenced by the designs for engraved ornament published by Vredeman de Vries. |

| Association | |

| Summary | Object Type This bed is in the typical style of carved wooden beds of the 1590s but it is remarkable for its large size. It is over 326 centimetres wide. The height was slightly reduced in the 19th century. The human figures carved on the headboard would originally have been brightly painted. Places The bed was probably made as a curiosity to attract customers to one of the inns at Ware, Hertfordshire. Ware is 22 miles from London, then a day's journey on horseback or by coach. The town had many inns in the 1590s. Historical Associations The bed has been famous since it was made. William Shakespeare mentioned it in his play Twelfth Night, first performed in 1601. The contemporary playwright Ben Jonson called it 'the great bed at Ware' in a play in 1609. Visitors often carved their initials on the bed or applied red wax seals, which are still visible on the bedposts and headboard today. |

| Associated objects |

|

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | W.47:1 to 28-1931 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | September 28, 1998 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest