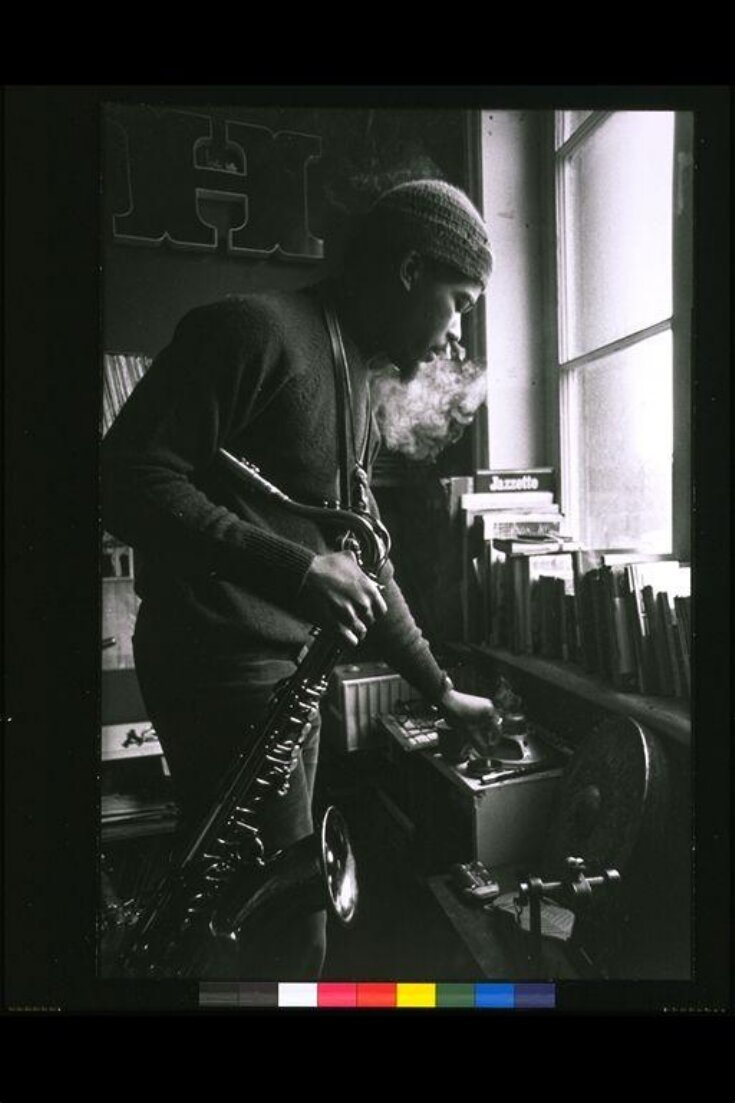

Kenneth Terroade in a Flat in Putney, London

Photograph

July 1971 (photographed)

July 1971 (photographed)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Gelatin silver print on paper

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Kenneth Terroade in a Flat in Putney, London (assigned by artist) |

| Materials and techniques | photographic paper, gelatin silver print |

| Brief description | Wilmer, Val. 'Kenneth Terroade in a flat in Putney, London, July 1971.' Gelatin-silver print. |

| Physical description | Gelatin silver print on paper |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Acquired from the Artist in 1973. |

| Object history | 'This collection of sixty-five items was selected for an exhibition in 1973, and printed by Valerie Wilmer. They are all black and white prints mounted on thin card, with a fine black border printed into the edge. None of the prints are signed.’ [Taken from Departmental Circulation Register 1973]. This set of photographs formed the 1973 exhibition 'Jazz Seen: The Face of Black Music'. The following is the original text from the exhibition brochure: Jazz Seen – The Face of Black Music An exhibition of photographs by Valerie Wilmer, arranged by the Circulation Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Foreword A distinguished writer about music, the late Ernest Newman, once defined a good music critic as being a musician right up to the point of putting pen to manuscript paper or hand to instrument. The same involvement and understanding is demanded of a jazz photographer if the results are not to be just subjective impressions of an alien world. Much ‘artistic’ photography in the field of jazz and the blues is plagued by romanticism – the smoke and sweat syndrome, we might say. Valerie Wilmer lives in the jazz world as a photographer and writer. And having said as much I must immediately correct myself, for jazz is only one manifestation of the black music which she depicts and for which she speaks in her introduction. About its fundamental role in 20th century music, does she protest too much? Impossible. The music of black America has for decades suffered a despoliation at the hands of the ‘music industry’ which should give serious concern to ecologists with the conservation of the world's resources at heart. Valerie Wilmer’s pictures never aim to clothe an alleged ‘jazz scene’ in glamour or mystique. They show things as they are – and they are – in many instances, rough. The look of ineffable boredom and weariness on Duke Ellington’s face at T.V. rehearsal reflects a life which, even at the top, offers fame, fortune, comfort even, only at the cost of ceaseless work and travel. Some of the younger musicians would put the Duke and his men among the lucky ones. The music which they themselves inherited and which they study, teach and propagate has ludicrously few outlets in either concert or ‘showbiz’ fields which it can call its own, and they are dwindling rather than increasing. Then there are those – the New Orleans veterans, the church singers, the blues men – to whom music is not a matter of profit and loss insofar as it, along with eating, drinking, laughing, talking and making love, is counted among the good things in life. This is not the place to investigate the source of the dynamic vitality which for seven decades – from ragtime and ‘negro spirituals’ through Dixieland jazz, big band swing and boogie-woogie to the blues, rock and soul music of today’s pop – has contributed fuel and energy unstintingly to the popular music of the Western World. Watching jazz musicians like Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet, Coleman Hawkins or Archie Shepp in action, one sometimes got the feeling that, if the instrument was suddenly snatched from their mouths, the music would go on pouring out unchecked. In Valerie Wilmer’s pictures of musicians in performance, whether it be in a crowded auditorium or for a few friends in a back room, one feels the same self-generating energy. From a flat landscape of toil, tedium, fatigue, sometimes squalor, often frustration, the music erupts. In her introduction, Valerie Wilmer pays tribute to distinguished fellow-artists. I will say what she cannot – that she herself belongs among them. Humphrey Lyttelton 1973 Introduction In every Western city and, indeed, in several Eastern ones, the rhythms, forms and timbres of Afro-American music are not only commonplace, they have become the norm for so-called ‘popular’ music. Black America brought about a cultural revolution at the turn of the century by changing the course and the nature of instrumental and vocal music, both in their written and improvised forms, but has received little credit for its corporate genius. Black Music is a term which many whites find questionable if not actually offensive. They argue that people of all races can and do play jazz and the blues, yet there seems to be some barrier against acknowledging the actual creative source of the music. For example: there is a certain style of piano-playing that has become almost mandatory in today’s popular music on both sides of the Atlantic. The general public have accepted this unquestioningly as part of the everyday musical backdrop and, because of its essentially appealing nature, warmly espoused it. Yet they are quite ignorant of the fact that this same piano style can be heard every Sunday in any church in Black America with the price of a piano. Just as the argot of Black America has penetrated the vocabulary of white youth with only the philologists being aware of it, so the so-called “non-legitimate” approach to instrumental and vocal technique is the standard one today outside the symphonic field. Used in a musical context, the term “legitimate” means “European”, which in turn implies that any non-European technique is illegitimate. “Legitimate” also suggests conforming to a standard, and that is something alien to Black Music for, as is pretty common knowledge, nothing is ever played the same way twice in jazz and the blues. To me, every Black musician is an iconoclast whether or not he or she is aware of it. Should that be in dispute, unravel the threads from which the fabric of contemporary music has been woven. Simple work-songs and field hollers helped relieve the monotony and pain of forced labour and served as a secret means of communication between slaves forbidden to speak. The blues is – and was – in turn catharsis, folk-history, oral philosophy and entertainment. In the churches where the solo singer habitually stretches one syllable over several notes of the scale, antiphony or the call-and-response pattern to be found in all areas of Black Music prevails. From all these basic roots up to the sophisticated voicings and orchestrations of Duke Ellington, Black Music is the sound that dominates the twentieth century. The impact of this music in all its forms is usually starkly dramatic. To the photographer, then, the visual aspect of the live performance usually evokes a similar emotive response to that experienced by the listener, but it has seldom gone any deeper. Few photographers are interested in showing who the musician is when he or she is not actually involved in creativity, or in earning a living. There are three notable exceptions: Dennis Stock of Magnum, whose book “Jazz Street” is the classic look at the world of the musicians, the late Tony Ray-Jones whose delicate photographs of New Orleans survivors are in the collections of the Royal Photographic Society, and Roy De Carava, the Black New Yorker who collaborated with the late Langston Hughes on his unforgettable Harlem vignette, “The Sweet Flypaper of Life”. For most others, the subject is almost too “picturesque”, and as they fall into the unfortunate trap of regarding their subject as object, reality fades in favour of composition and “impact”. My concern is with the interior of the person rather than the exterior, and I hope that as well as capturing the essence of the music, I have managed to explain something about the people, known and unknown, who appear in these photographs. Valerie Wilmer, March 1973 Catalogue Valerie Wilmer was born in Yorkshire in 1941. She spent her childhood in London, and by her late teens was involved with musicians, in their work and in their lives. Her first contact with the world of jazz was through the London pubs, where it was played in various idioms by British musicians laced with visiting “names” from America. One of her first photographs was taken of Louis Armstrong on a concert tour. Friendships with Americans lead Valerie to make frequent trips to America, where, with her gift for penetrating any situation without arousing hostility, she was immediately absorbed into whatever branch of the music she could find to photograph and write up. Her photographs, at first merely illustrations for her articles, became gradually more important. She developed, almost without realising it at first, the ability to use photography as a medium for transmitting her own particular tender, perceptive vision of the world of black music. Outlets for her work have mostly been in the music press, and with the graphics associated with record production. Her photographs have been used in films – notably in John Jeremy’s “Jazz is Our Religion”, which is mostly composed of Valerie’s stills – and in books on the music. Valerie Wilmer is a committed campaigner, and a writer of very direct prose, but in the photographs there is no trace of preaching, nor of the exploitation of those clichés that lesser photographers constantly fall back on when dealing with negroes and/or jazz. She looks at the music world from inside, and her camera is less a spectator, than an interpreter of a society that exists alongside the conventional image of American life that most of us hold. Our image of the music too, is modified after seeing Valerie’s pictures. It becomes real in a visual sense that matches the unquenchable reality of the sound itself. The prints have been made, and the following captions suppled, by Val Wilmer: |

| Subject depicted | |

| Bibliographic reference | Taken from Departmental Circulation Register 1973 |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | CIRC.235-1973 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | August 1, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSON