The Oxburgh Hangings

Panel

ca. 1585 (made)

ca. 1585 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Object Type

Making up large decorative hangings from a number of smaller panels which were then applied to a sympathetic background material, was a popular pastime of well-to-do ladies in the 16th century. This allowed a group of women to embroider individual panels at the same time. If required, the hanging could be dismantled at a later stage and the panels re-used.

Historical Associations

Surviving embroideries can rarely be identified as having been owned or worked by royalty. Unfortunately for the doomed Mary, Queen of Scots, she had plenty of time while imprisoned to work on numerous embroideries, some of which include her initials or cipher. This activity must have both filled her time and occupied her mind as many of the emblems or mottoes used have more significance than is immediately apparent.

Subjects Depicted

Mary's personal cipher is not included but her identity would have been clear to the recipient. Her emblem of the marigold turning towards the sun and a dog, symbolising a faithful friend are seen with the royal arms of Scotland surrounded by the Order of the Thistle.

A 1586 Inventory of Mary's belongings lists: ' a square of petit point, with a single emblem in the middle and others around (it) with the arms of France, Scotland, Spain and England ', which may well be this panel.

Making up large decorative hangings from a number of smaller panels which were then applied to a sympathetic background material, was a popular pastime of well-to-do ladies in the 16th century. This allowed a group of women to embroider individual panels at the same time. If required, the hanging could be dismantled at a later stage and the panels re-used.

Historical Associations

Surviving embroideries can rarely be identified as having been owned or worked by royalty. Unfortunately for the doomed Mary, Queen of Scots, she had plenty of time while imprisoned to work on numerous embroideries, some of which include her initials or cipher. This activity must have both filled her time and occupied her mind as many of the emblems or mottoes used have more significance than is immediately apparent.

Subjects Depicted

Mary's personal cipher is not included but her identity would have been clear to the recipient. Her emblem of the marigold turning towards the sun and a dog, symbolising a faithful friend are seen with the royal arms of Scotland surrounded by the Order of the Thistle.

A 1586 Inventory of Mary's belongings lists: ' a square of petit point, with a single emblem in the middle and others around (it) with the arms of France, Scotland, Spain and England ', which may well be this panel.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | The Oxburgh Hangings (popular title) |

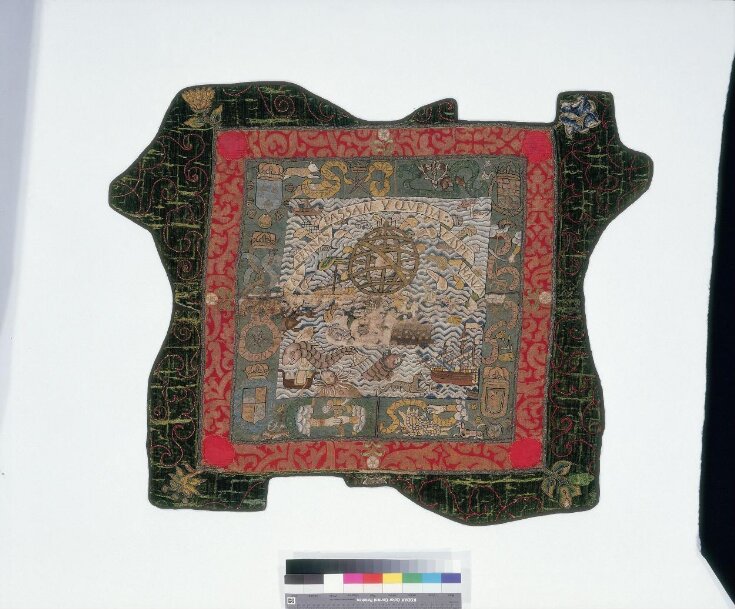

| Materials and techniques | Embroidered linen canvas with gold, silver and silk threads, lined |

| Brief description | Textile panel 'The Oxburgh Hangings' of embroidered linen canvas with gold, silver and silk threads, possibly made by Elizabeth Talbot and Mary Queen of Scots, probably made in Tutbury, ca. 1585 |

| Physical description | Textile panel of embroidered linen canvas with gold, silver and silk threads in tent stitch. With a design of feathers falling about an armillory sphere which stands on a rock in the midst of the sea. The sea is peopled by sea monsters and ships. Motto 'LAS PENNAS PASSAN Y QVEDA LA SPERANZA' (Sorrow pass and hope abides), Embroidered border containing the Royal Arms of England, France, Scotland and Spain with the devices of various orders and emblematic designs. Lined. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | 'LAS PENNAS PASSAN Y QVEDA LA SPERANZA' (Inscribed on the large central panel)

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Presented by Art Fund |

| Object history | Three panels signed ES for Elisabeth Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury (1527-1608) The large central panel probably made in Tutbury Castle, Staffordshire; the smaller panels probably made at Sheffield Castle, South Yorkshire |

| Summary | Object Type Making up large decorative hangings from a number of smaller panels which were then applied to a sympathetic background material, was a popular pastime of well-to-do ladies in the 16th century. This allowed a group of women to embroider individual panels at the same time. If required, the hanging could be dismantled at a later stage and the panels re-used. Historical Associations Surviving embroideries can rarely be identified as having been owned or worked by royalty. Unfortunately for the doomed Mary, Queen of Scots, she had plenty of time while imprisoned to work on numerous embroideries, some of which include her initials or cipher. This activity must have both filled her time and occupied her mind as many of the emblems or mottoes used have more significance than is immediately apparent. Subjects Depicted Mary's personal cipher is not included but her identity would have been clear to the recipient. Her emblem of the marigold turning towards the sun and a dog, symbolising a faithful friend are seen with the royal arms of Scotland surrounded by the Order of the Thistle. A 1586 Inventory of Mary's belongings lists: ' a square of petit point, with a single emblem in the middle and others around (it) with the arms of France, Scotland, Spain and England ', which may well be this panel. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | T.33-1955 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | April 8, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest