Tile

ca. 1650 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

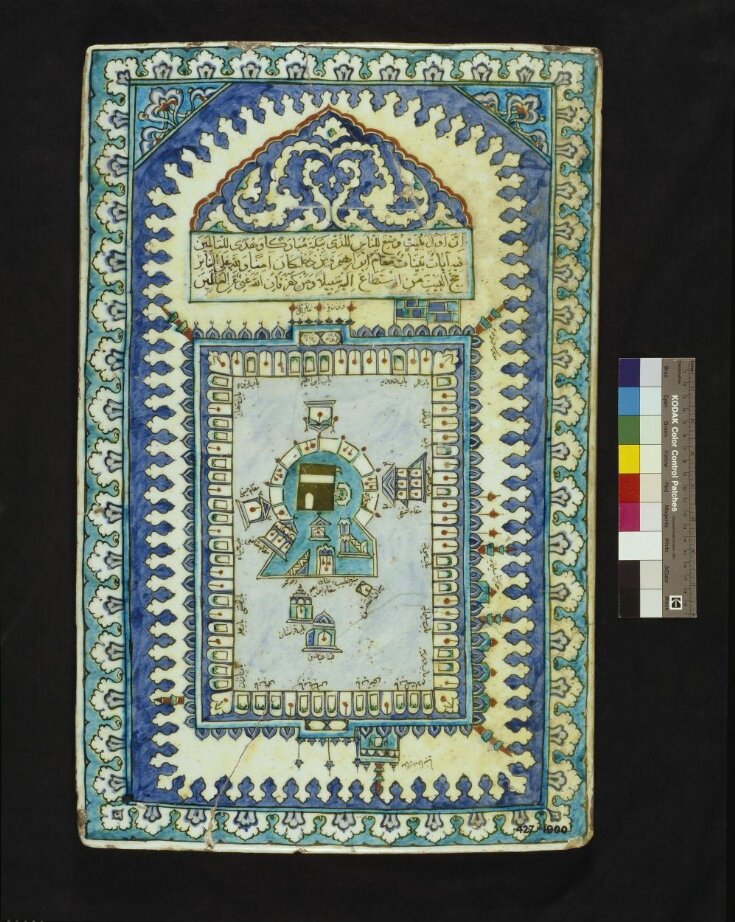

The Middle East is the focus of Muslims’ prayers because it contains the city of Mecca in western Saudi Arabia and, more precisely, the structure known as the Ka’bah, which stands at the centre of the city. This cube-like stone building was a religious shrine long before the Prophet’s time, and the Qur’an relates that it was originally built by the Jewish patriarch Abraham as the first House of God. Later it fell into the hands of idolaters, and it was Muhammad’s role to restore it to its proper use, by worshippers of the One true God.

This tile was probably made to commemorate a pilgrimage to Makkah (Mecca). The main pilgrimage, the Hajj, occurs once a year, at the time of the Feast of Sacrifice, and the elaborate rites on this occasion culminate in visits to the Ka’bah in the Noble Sanctuary, which is often depicted on the certificates and mementos pilgrims acquire to record their journey. Here the sanctuary is represented diagrammatically as though seen from the north-east (which is at the bottom). The various structures within the surrounding arcades are labelled, and the space immediately above the diagram is filled with a relevant quotation from the Qur’an (surah III, verses 96–97), which enjoins the performance of the Hajj on all believers who can afford it.

This tile was probably made to commemorate a pilgrimage to Makkah (Mecca). The main pilgrimage, the Hajj, occurs once a year, at the time of the Feast of Sacrifice, and the elaborate rites on this occasion culminate in visits to the Ka’bah in the Noble Sanctuary, which is often depicted on the certificates and mementos pilgrims acquire to record their journey. Here the sanctuary is represented diagrammatically as though seen from the north-east (which is at the bottom). The various structures within the surrounding arcades are labelled, and the space immediately above the diagram is filled with a relevant quotation from the Qur’an (surah III, verses 96–97), which enjoins the performance of the Hajj on all believers who can afford it.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Fritware, underglaze painted in cobalt blue and turquoise, glazed |

| Brief description | Tile with a depiction of the Ka'ba and Sacred Enclosure at Mecca, Turkey (probably Iznik), about 1650. |

| Physical description | Large rectangular stonepaste tile, underglaze-painted in a typical Iznik pallette of red, olive green, cobalt and turquoise blue on a white ground. The tile is decorated with a ‘birds-eye’ view of the Masjid al-Haram, or Great Mosque, at Mecca. This image has been produced by underglaze-painting with the artist using red, olive green, cobalt and turquoise blue colours on a white background. These colours were used widely by the Iznik potters, forming a standard palette. Islam’s holiest shrine, the Ka’ba, is illustrated in the centre and is surrounded by other important structures, labelled in Arabic, and enclosed by a rectangular portico which runs around the courtyard. This decoration makes the tile a useful teaching tool for introducing and exploring some of the most important sites and beliefs in Islam. The upper third of the tile has a panel which contains verses from the Qur’an, written in naskhi, a cursive script favoured by the Ottomans. The text panel is surmounted by a lunette filled with cloud-scrolls, a motif adopted from Chinese art which was frequently used on dishes produced in the Ottoman pottery industry at Iznik. The composition of the whole tile is unified by the double border of cresting. It can be dated to the mid seventeenth century, on comparison with other such tiles which do actually carry a date, and it was probably made at Istanbul, after the court pottery industry had moved there from Iznik. The passage quoted in the inscription panel contains verses 96-97 of sura 3 (Al -‘Imran) of the Qur’an, which exhort all Muslims to undertake the pilgrimage (or hajj) to Mecca at least once within his or her lifetime, if able to do so. This was the same passage as was embroidered in gold on the silk covering of the keys for the door of the Ka’ba. It reads: “[96] The first House established for the worship of God by men was that at Mecca, a place full of blessing and guidance for all beings. [97] Therein are clear signs, such as the station of Abraham, and whoever enters it is in security. Pilgrimage (hajj) to the House is a duty which every man owes to God, if he can afford the journey. But if any deny faith, God is not in need of any of His creatures”. This passage alludes to the Muslim belief that the Ka’ba at Mecca – which is known by Muslims as the Bayt Allah or House of God – was the first temple, built by the Prophet Abraham on a site whose holy associations go back as far as Adam and Eve. The “station of Abraham” mentioned in the passage refers to the place where Abraham prayed after he had finished building the Ka’ba, and its location – depicted on the tile as a small arched doorway immediately below the Ka’ba – is labelled in naskhi script on the tile. The names of the various gates which open into the sanctuary are also labelled, as are some of the minarets and pavilions which surround it. The tile also depicts the Mosque’s minbar, or pulpit, and the ‘stations’ at which the imams, or heads, of the four Islamic legal schools should stand. All the holy sites of Mecca have therefore been marked, perhaps in the same way that today place-names might be marked on a postcard. The modern analogy is a good one because tiles like this were probably made to mark the fact that the owner or patron had completed their duty of pilgrimage to Mecca. Similar depictions also exist on paper, in pilgrimage guides and prayer books, as well as on instruments for determining the direction and the times of prayer. Tiles like this might have been mounted on their own on a wall, or set within a decorative frieze of tiles. In general they are found mounted on the qibla wall, or that pointing in the direction of Mecca, but their function was not the same as the mihrab, or marker incorporated into the wall of a mosque to indicate the direction of prayer. Their primary function was probably that of a religious reminder, in the same way as today prayer carpets often feature depictions of Mecca in their designs. (Mariam Rosser-Owen, text of TES article) |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Marks and inscriptions | Qur'an Sura 3: 96-97 (Arabic; Naskhi; top third of tile; painted)

|

| Gallery label | Jameel Gallery

4 Tile with the Great Mosque at Mecca

Turkey, probably Iznik

About 1650

A bird’s-eye view shows the mosque as it was in the 17th century. The Ka’bah is the square building in the centre, draped in black silk. The text above is from the Qur’an. It states that all Muslims who can afford to must make a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in their lifetime.

Fritware painted under the glaze

Museum no. 427-1900

(Jameel Gallery) |

| Places depicted | |

| Summary | The Middle East is the focus of Muslims’ prayers because it contains the city of Mecca in western Saudi Arabia and, more precisely, the structure known as the Ka’bah, which stands at the centre of the city. This cube-like stone building was a religious shrine long before the Prophet’s time, and the Qur’an relates that it was originally built by the Jewish patriarch Abraham as the first House of God. Later it fell into the hands of idolaters, and it was Muhammad’s role to restore it to its proper use, by worshippers of the One true God. This tile was probably made to commemorate a pilgrimage to Makkah (Mecca). The main pilgrimage, the Hajj, occurs once a year, at the time of the Feast of Sacrifice, and the elaborate rites on this occasion culminate in visits to the Ka’bah in the Noble Sanctuary, which is often depicted on the certificates and mementos pilgrims acquire to record their journey. Here the sanctuary is represented diagrammatically as though seen from the north-east (which is at the bottom). The various structures within the surrounding arcades are labelled, and the space immediately above the diagram is filled with a relevant quotation from the Qur’an (surah III, verses 96–97), which enjoins the performance of the Hajj on all believers who can afford it. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 427-1900 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | April 2, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest