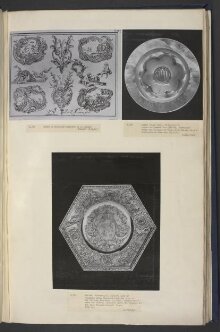

Chalice and Paten

1518-1519 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Object Type

This chalice and paten, or plate, were made before the Reformation in England to hold the consecrated wine and bread used during Mass, the central service of Christian worship. After the Reformation, the authorities of the new Church of England renamed this service Holy Communion, and the vessels were called a communion cup and cover. This chalice and paten continued in use after the Reformation by generations of the Roman Catholic family who owned them. The paten was often placed on top of the chalice, acting as a cover.

Design & Use

In design this example follows the standard form that had developed throughout Europe by the late 15th century, and which was dictated by the liturgical practices. The relatively small bowl was appropriate because it was only the priest who drank the consecrated wine. The knop, or knot at mid-point of the stem, was where the priest grasped the chalice when he raised it high for the consecration. The spreading foot was necessary to stabilise the chalice. The lobed form was to prevent the chalice from rolling when laid sideways on the altar to drain.

History

Most church silver was melted down in the upheavals of the Reformation. Very few pre-Reformation examples survive. This elaborate example was probably ordered for, and subsequently survived in, a private chapel of the aristocracy.

This chalice and paten, or plate, were made before the Reformation in England to hold the consecrated wine and bread used during Mass, the central service of Christian worship. After the Reformation, the authorities of the new Church of England renamed this service Holy Communion, and the vessels were called a communion cup and cover. This chalice and paten continued in use after the Reformation by generations of the Roman Catholic family who owned them. The paten was often placed on top of the chalice, acting as a cover.

Design & Use

In design this example follows the standard form that had developed throughout Europe by the late 15th century, and which was dictated by the liturgical practices. The relatively small bowl was appropriate because it was only the priest who drank the consecrated wine. The knop, or knot at mid-point of the stem, was where the priest grasped the chalice when he raised it high for the consecration. The spreading foot was necessary to stabilise the chalice. The lobed form was to prevent the chalice from rolling when laid sideways on the altar to drain.

History

Most church silver was melted down in the upheavals of the Reformation. Very few pre-Reformation examples survive. This elaborate example was probably ordered for, and subsequently survived in, a private chapel of the aristocracy.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Silver, partially gilded, with enamel |

| Brief description | The Bedingfield Chalice and Paten, silver, partially gilded, with enamel, England (London), 1518-1519 |

| Physical description | Chalice and paten, silver, partially gilded, with enamel |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Purchased with Art Fund support and assistance from the Murray Bequest |

| Object history | Maker's mark: a fish Made in London by an unidentified maker V&A Exhibition RF.2003/51 |

| Summary | Object Type This chalice and paten, or plate, were made before the Reformation in England to hold the consecrated wine and bread used during Mass, the central service of Christian worship. After the Reformation, the authorities of the new Church of England renamed this service Holy Communion, and the vessels were called a communion cup and cover. This chalice and paten continued in use after the Reformation by generations of the Roman Catholic family who owned them. The paten was often placed on top of the chalice, acting as a cover. Design & Use In design this example follows the standard form that had developed throughout Europe by the late 15th century, and which was dictated by the liturgical practices. The relatively small bowl was appropriate because it was only the priest who drank the consecrated wine. The knop, or knot at mid-point of the stem, was where the priest grasped the chalice when he raised it high for the consecration. The spreading foot was necessary to stabilise the chalice. The lobed form was to prevent the chalice from rolling when laid sideways on the altar to drain. History Most church silver was melted down in the upheavals of the Reformation. Very few pre-Reformation examples survive. This elaborate example was probably ordered for, and subsequently survived in, a private chapel of the aristocracy. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.76&A-1947 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | March 27, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest