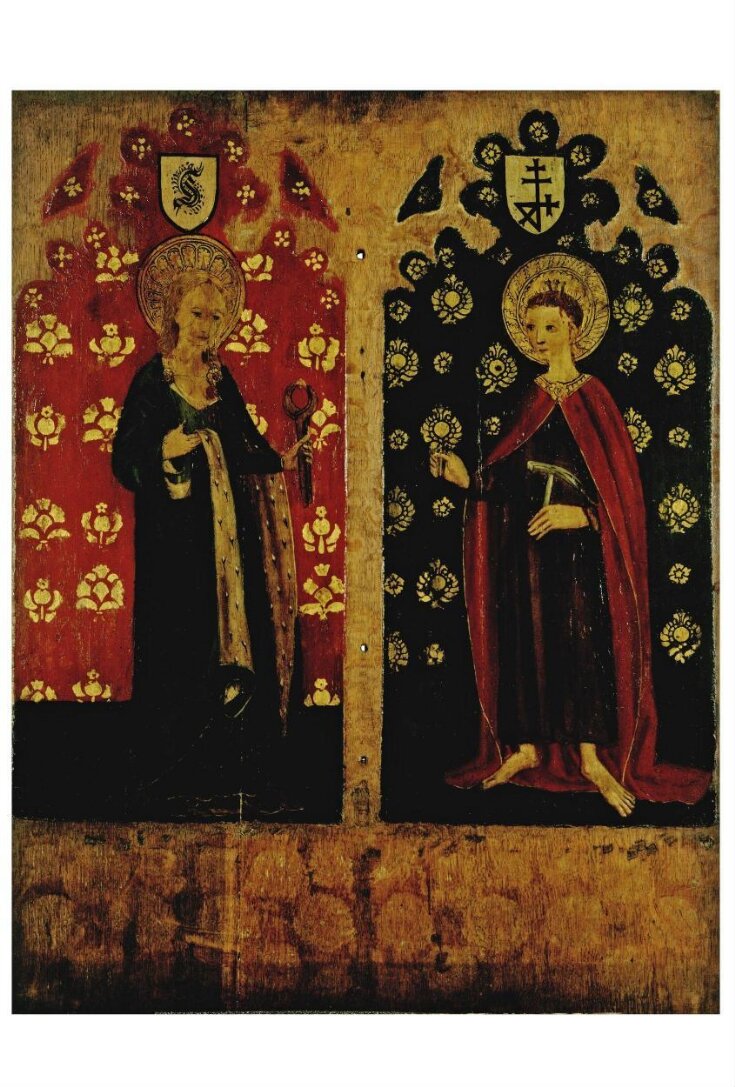

St Agatha Holding Pincers and a Breast; William of Norwich with Three Nails in His Head (panel from a rood screen)

Panel

ca. 1450-1470 (made)

ca. 1450-1470 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Object Type

Painted rood screens such as this were an essential part of the structure and decoration of a mediaeval church. The screen separated the priest and the altar from the congregation. It takes its name from the rood (cross) mounted above it. Christ on the cross was usually flanked by figures of the Virgin Mary and St John.

Subjects Depicted

The delicate interlaced framework of carved and gilded wood (known as 'tracery') that once surrounded each of the painted areas is lost. The figures were considerably repainted and perhaps altered in the 19th century. According to legend, the early Christian martyr St Agatha, of whom almost nothing is known, was tortured for her faith, which resulted in her death. The torment most frequently depicted was the amputation of her breasts. She is often represented in pictures carrying them before her. Here she is shown holding one of her breasts in a pair of pincers, the instrument of her martyrdom. The existence of William of Norwich is more historically certain. As a 12-year-old boy he was murdered in 1144 in a wood outside the city of Norwich. The Church claimed that he had been slaughtered by the Jews.

Painted rood screens such as this were an essential part of the structure and decoration of a mediaeval church. The screen separated the priest and the altar from the congregation. It takes its name from the rood (cross) mounted above it. Christ on the cross was usually flanked by figures of the Virgin Mary and St John.

Subjects Depicted

The delicate interlaced framework of carved and gilded wood (known as 'tracery') that once surrounded each of the painted areas is lost. The figures were considerably repainted and perhaps altered in the 19th century. According to legend, the early Christian martyr St Agatha, of whom almost nothing is known, was tortured for her faith, which resulted in her death. The torment most frequently depicted was the amputation of her breasts. She is often represented in pictures carrying them before her. Here she is shown holding one of her breasts in a pair of pincers, the instrument of her martyrdom. The existence of William of Norwich is more historically certain. As a 12-year-old boy he was murdered in 1144 in a wood outside the city of Norwich. The Church claimed that he had been slaughtered by the Jews.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | St Agatha Holding Pincers and a Breast; William of Norwich with Three Nails in His Head (panel from a rood screen) |

| Materials and techniques | Tempera on oak panel |

| Brief description | Panel from a rood screen, entitled: St Agatha Holding Pincers and a Breast; William of Norwich with Three Nails in His Head, commissioned by Ralph Segrym, from the Chapel of St Mary in St John's Church, Maddermarket, Norwich, painted in Norwich by an unidentified artist ca. 1450 -1470. |

| Physical description | A panel depicting two full-length figures: on the left-hand side, a female saint, in a blue ermine-lined red mantle over a green robe, with pincers in her left hand and holding an amputated breast; on the right-hand side, a male figure in a red mantle over a brown robe, with bare feet, three nails in his head, three nails in his right hand and a hammer in his left hand. The backgrounds of each figure are alternately red and green, the female saint being on red, and are deocrated with pomegrante and flower patterns in gold. Above the male figure is the device and above the female saint the initials of Ralph Segrym, merchant of Norwich, the donor of the panels. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Marks and inscriptions | Marked with the device and initials of the donor Ralph Segrym |

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | From a rood screen together with another panel in the museum: St Leonard with Crozier and Manacles; St Catherine with Sword and Book (Museum no. 23-1894). Commissioned by Ralph Segrym (died 1472), a merchant who was Sheriff of Norwich in 1447, MP for Norwich in 1449 and Mayor in 1451 From the Chapel of St Mary in St John's Church, Maddermarket, Norwich. Painted in Norwich by an unidentified artist Exhibited at 'The Art of Faith: 3500 Years of Art and Belief in Norfolk' (Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery 02/10/2010-23/01/2011). |

| Historical context | The rood screen, also referred to as a choir or chancel screen, is a common feature in late medieval parish church architecture. It divides the chancel, the priest and altar, from the congregation in the nave. It is typically an ornate screen, constructed of wood, stone or wrought iron. The word rood derives from the Saxon word rood or rode, meaning “cross”. The screen is so called because it was surmounted by the Rood, a large figure of the crucified Christ. This was usually surrounded by statues of saints, commonly S. Mary and S. John. During the mid-15th century, the burgeoning class of economically prosperous city merchants appears not to have extended much patronage to painting. However, the building and decoration of churches was a different matter. A great many churches were constructed or added to in this period, such as Long Melford and Lavenham, Suffolk, of which considerable sums of money for the works were provided by secular donors. One notable exception of mercantile patronage to painting, in this period, was the Norfolk rood screens. Artistic activity during this period, which contains few major works of high quality, centres mainly on two media: stained glass and screen painting. Comparisons in artistic style may be made between these, partly perhaps because 15th century panel painting is found principally in rood screens, which being constructed with elaborate tracery framework, suggest a link with the general concept of window design. Despite slight degrees of stylistic continuity, the painted screens, a great number of which are found in East Anglia, show little connection with the style of local glass. This panel is painted with two full-length, nimbed figures in gold and colours. It is among the earliest examples of this form of English painting and one of the very few screens which can be dated. This panel depicts a female saint, on the left-hand side, in blue ermine-lined red mantle over a green robe, with pincers in her left hand holding what appears to be a breast. This corresponds to a bleeding wound at the figures left breast. These attributes are most commonly associated with Saint Agatha. The object is the pincers had previously been thought to be a tooth, commonly associated with S. Apollonia. On the right-hand side is a corresponding male figure, in a red mantle over a brown robe, with bare feet, three nails in his head, three nails in his right hand and a hammer in his left, objects attributed to William of Norwich, a folk-Catholic saint whose narrative is entrenched in the blood-libel and who was never officially canonised. The figures face each other with downcast eyes, standing alone apart from the objects in their hands. The backgrounds of each figure are alternately red and green, S. Agatha being on red, and are decorated with pomegranate and flower patterns in gold. Above William is the device and above S. Agatha, the initials of Ralph Segrym, merchant of Norwich, the donor of the panels. His initials enable the panel to be dated. The Maddermarket panels illustrate two characteristics common to artistic production of mid-15th century England; the influence exerted by an increasingly affluent merchant class and the possibility of gaining information about donors of screens, by inscriptions or documents relating to the people who provided them. Other notable examples of known donors are found at East Harling, Shelton and Long Melford. The donor of the Maddermarket panels, Ralph Segrym, whose initials can be found on each of the panels, became a freeman of Norwich in 1426/7 as a mercer. He served as chamberlain of the city from 1437 to 1439, as Sheriff in 1447, M.P in 1449 and Mayor in 1451. He participated in four other parliamentary elections at Norwich between 1442 and 1453, on the last occasion being described as an alderman. Segrym was a benefactor to Norwich and appears to have shown particular interest in the city’s prisoners, using money allocated by the will of John Wilbeye to charitable works to construct a separate prison for women in the city guildhall. He also financed the creation of a chapel outside the guildhall from his own funds. This may have been to serve prisoners there, for the dedication was to S. Barbara, the patron saint of prisoners, but it could have been used for chantries. Segrym’s interest in the welfare of prisoners may explain the inclusion of S. Leonard, a saint associated with the releasing of prisoners, on the Maddermarket panels. After his death, a memorial brass effigy of Segrym and his wife was placed above their tomb in the church of St John Maddermarket, Norwich. As indicated by the Maddermarket panels, donors were largely local lay figures, rich landowners or merchants. However, in lesser buildings it was more often quite humble people who provided church furnishings and decoration, acting together in guilds or even paying for just one or two panels of a screen. Piecemeal patronage was the general rule, and although one important figure or family may have provided the initial inspiration and finance for a large project, such as Anne Harling and her first two husbands at East Harling, many different people were involved in the long run, and in smaller churches it would have been unusual to find a unified scheme of decoration. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Association | |

| Summary | Object Type Painted rood screens such as this were an essential part of the structure and decoration of a mediaeval church. The screen separated the priest and the altar from the congregation. It takes its name from the rood (cross) mounted above it. Christ on the cross was usually flanked by figures of the Virgin Mary and St John. Subjects Depicted The delicate interlaced framework of carved and gilded wood (known as 'tracery') that once surrounded each of the painted areas is lost. The figures were considerably repainted and perhaps altered in the 19th century. According to legend, the early Christian martyr St Agatha, of whom almost nothing is known, was tortured for her faith, which resulted in her death. The torment most frequently depicted was the amputation of her breasts. She is often represented in pictures carrying them before her. Here she is shown holding one of her breasts in a pair of pincers, the instrument of her martyrdom. The existence of William of Norwich is more historically certain. As a 12-year-old boy he was murdered in 1144 in a wood outside the city of Norwich. The Church claimed that he had been slaughtered by the Jews. |

| Associated object | |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 24-1894 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | March 27, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest