1787 (published)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

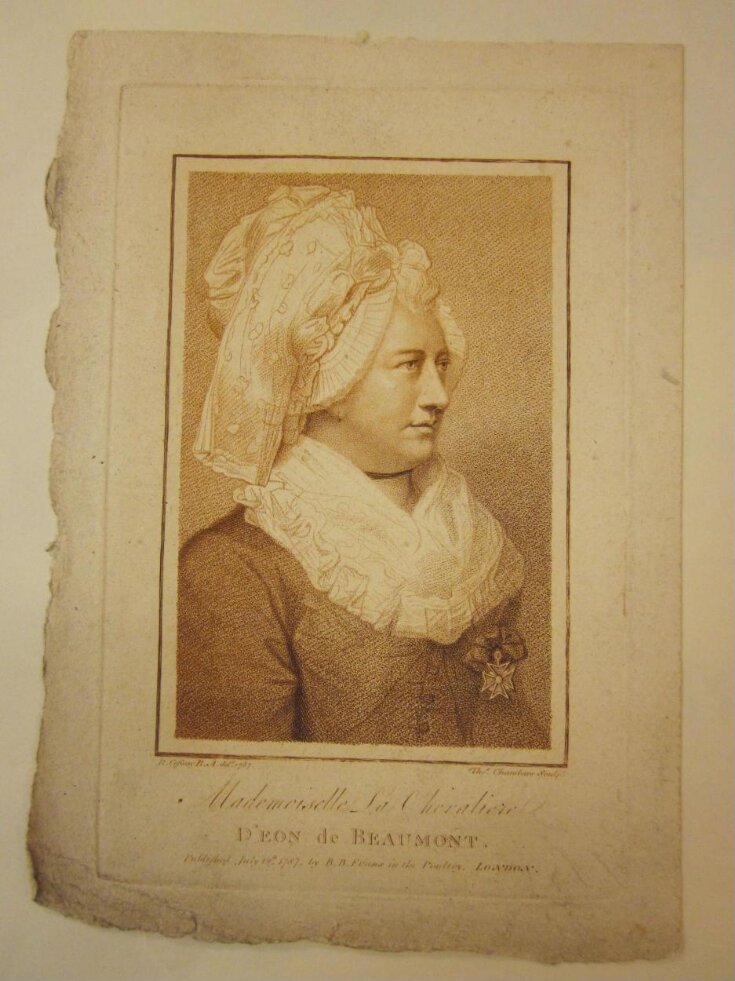

An engraved portrait of Mademoiselle La Chevalier D'Eon de Beaumont depicted in female dress wearing a large mob cap and a Croix de Saint-Louis.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Stipple engraving on paper |

| Brief description | Print by Thomas Chambars after Richard Cosway, portrait of the Chevalier D'Eon, stipple, Great Britain, 1787 |

| Physical description | An engraved portrait of Mademoiselle La Chevalier D'Eon de Beaumont depicted in female dress wearing a large mob cap and a Croix de Saint-Louis. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | 'R. Cosway R.A. delt 1787. Thos Chambars Sculpt. / Mademoiselle La Chevaliere / D'Eon de Beaumont. / Published July 12th 1787, by B. B. Evans in the Poultry, London.' (Lettered) |

| Credit line | Given by Mrs. Gabrielle Enthoven |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Bibliographic reference | Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée d'Éon de Beaumont, commonly referred to as the Chevalier d’Éon, (born Oct. 5, 1728, Tonnerre, France—died May 21, 1810, London), was a French secret agent, soldier, and fencer from whose name the term “eonism” is derived, denoting specifically male to female transvestism or transition.

Le Chevalier d’Eon joined 'Le Secret' as a spy in 1755 on the eve of the Seven Years War. Their first mission was to Russia to gain the trust and ear of the Tzarina Elizabeth. This appears to be the first record of the Chevalier dressing as a woman for the purposes of espionage, taking the name Mademoiselle Lia de Beaumont. The Tzarina was described as more likely to respond to the attentions of 'a pleasant young woman', coupled with the fact that border controls put in place by the English prohibited French access to Russia. However, women and children were permitted to cross. The truth of whether this mission ever took place at all is contested, like many other mysteries in the Chevalier’s life. After continued good service to the nation as a dragoon captain, they went to London in 1762 returning to Versailles the next year with the ratification of the Treaty of Paris. They received the cross of St. Louis and returned to London, this time with ambassadorial status and instructions from the King for further espionage to rebuild France’s fortunes by invading England following the loss of their American colonies. However, after a quarrel with another ambassador, the Chevalier was fired and ordered to return to France but they refused to go, instead opting to air French secrets in a libellous and scandalous publication of diplomatic letters in 1764.

Forced into exile, they remained in London and speculation mounted as to the Chevalier’s gender with bookmakers setting odds from 1771 to gamble on the question. This posed a considerable danger to the Chevalier who couldn’t leave their home without guards for the threat of people attempting to strip off their clothes in the street. In 1775 they signed an agreement to hand back any official documents to France and be publicly recognised as a woman by the King. Living out the remainder of their life in London as a woman, they died in 1810 and were interred at St Pancras Old Church. An autopsy performed two days after death certified them as “male-bodied” but with "unusual roundness in the formation of limbs...[and] breast remarkably full" giving rise to speculations more recently that they may have been intersex. The complexity of the Chevalier's gender identity has become a central narrative in the search for gender non-conforming histories in 18th century Europe. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | E.963-1928 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 30, 2009 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest