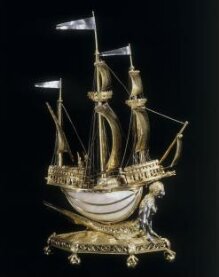

The Burghley Nef

Salt Cellar

1527-1528 (made)

1527-1528 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Medieval manuscript illuminations from as early as the 14th century show similar nefs acting as lavish and public status symbols on the dining table, often marking the place of the host or honoured guest. The January miniature from the Très Riches Heures manuscript (c 1413–16) of Jean, Duc de Berry, shows a large nef placed to the left of the principal diner, as does the painting for the same month in the Flemish-made Grimani Breviary, of about 1510-20. Nefs were particularly prized in France and Italy, where noble and royal inventories from dating back to the 13th century list copious silver and gold ships, but their appeal was more widespread, reaching Germany, Spain and the Low Countries. In a culture where gift-giving played a major role in domestic diplomacy, nefs would have satisfied the contemporary passion for giving and receiving ingenious, finely crafted goldsmiths’ work. The Burghley nef would probably have been specially commissioned, but it is clear from contemporary depictions of goldsmiths’ shops that smaller, less elaborate nefs were part of the medieval goldsmith’s stock-in-trade.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Title | The Burghley Nef (popular title) |

| Materials and techniques | Nautilus shell with parcel-gilt silver mounts, raised, chased, engraved and cast, and pearls. |

| Brief description | The Burghley Nef, nautilus shell mounted in silver, parcel-gilt, Paris, 1527-28. |

| Physical description | A parcel-gilt (partly-gilt) salt cellar resembling a late medieval ship, the hull made from a nautilus shell. Details include a battlemented poop, which encloses a detachable salt-cellar, and fore-castle, three masts with fighting tops (two of which are hung with a garland of pearls), sails, pennants and (later) rigging, a figurehead in the shape of a wolf's head, small figures of sailors manning the deck and cannon or climbing the rigging, as well as two smaller figures of Tristan and Iseult seated at the bottom of the central mainmast playing a game of chess. The whole ship sits on the back of mermaid who rests on an hexagonal base of rippling waves with six ball-and-claw feet. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Supported by The Art Fund (Cochrane Trust) and the Goldsmiths' Company |

| Object history | Discovered in the basement of Burghley House near Stamford in 1956 by silver specialist Arthur Grimwade, then head of Christie's silver department, while he was compiling an inventory of the silver belonging to the late 5th Marquess of Exeter. Documentary evidence does not go earlier than 1844, when a dated handwritten note recording the acquisition of ‘a small ship’, possibly this nef, was added to the 1824 plate book at Burghley House. Sold on 17 July 1959 as lot 118 to London silver dealers S.J. Phillips when the 6th Marquess of Exeter auctioned part of his silver collection at Christie's. Purchased by the V&A in the same year with the assistance of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths and the National Art Collections Fund. |

| Historical context | Medieval manuscript illuminations from as early as the 14th century show similar nefs acting as lavish and public status symbols on the dining table, often marking the place of the host or honoured guest. The January miniature from the Très Riches Heures manuscript (c 1413–16) of Jean, Duc de Berry, shows a large nef placed to the left of the principal diner, as does the painting for the same month in the Flemish-made Grimani Breviary, of about 1510-20. Nefs were particularly prized in France and Italy, where noble and royal inventories from dating back to the 13th century list copious silver and gold ships, but their appeal was more widespread, reaching Germany, Spain and the Low Countries. In a culture where gift-giving played a major role in domestic diplomacy, nefs would have satisfied the contemporary passion for giving and receiving ingenious, finely crafted goldsmiths’ work. The Burghley nef would probably have been specially commissioned, but it is clear from contemporary depictions of goldsmiths’ shops that smaller, less elaborate nefs were part of the medieval goldsmith’s stock-in-trade. Nefs were less common in England, where the grand salt fulfilled a similar symbolic function, but descriptions of them occur in royal household accounts. A royal inventory of 1348 notes one presumably brought to England by Philippa of Hainault on her marriage to Edward III, and a record of 1437 indicates that Henry VI possessed two sumptuous examples – one silver-gilt, the other of gold embellished with rubies and pearls. These eye-catching table sculptures fulfilled practical as well as social uses, and were frequently described in contemporary accounts as personal containers for napkins, cutlery, spices and even trencher-plates. The 1380 inventory of Charles V of France describes a lidded ‘navette’ (little nef) made of gold, which contained his spoon, knife, fork and a ‘cup of essay’, a vessel used for ceremonial wine tasting at the beginning of the meal. The Burghley nef has a detachable dish set into the poop deck, strongly suggesting it was used as a saltcellar. The grandeur of the container expressed the importance of this precious and still relatively expensive commodity, which was valued not only as a taste enhancer but also as a means of preserving perishable foods like fish and meat. The nef’s marine imagery was particularly suited to its intended contents but also reflected a contemporary trend for fantastical salts, as seen in a design for a salt one by Pisanello of c 1448-9 in the form of a ship supported on the back of a dragon (Musée du Louvre, Paris). |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Medieval manuscript illuminations from as early as the 14th century show similar nefs acting as lavish and public status symbols on the dining table, often marking the place of the host or honoured guest. The January miniature from the Très Riches Heures manuscript (c 1413–16) of Jean, Duc de Berry, shows a large nef placed to the left of the principal diner, as does the painting for the same month in the Flemish-made Grimani Breviary, of about 1510-20. Nefs were particularly prized in France and Italy, where noble and royal inventories from dating back to the 13th century list copious silver and gold ships, but their appeal was more widespread, reaching Germany, Spain and the Low Countries. In a culture where gift-giving played a major role in domestic diplomacy, nefs would have satisfied the contemporary passion for giving and receiving ingenious, finely crafted goldsmiths’ work. The Burghley nef would probably have been specially commissioned, but it is clear from contemporary depictions of goldsmiths’ shops that smaller, less elaborate nefs were part of the medieval goldsmith’s stock-in-trade. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.60-1959 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | January 16, 2003 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest