Cassone

ca. 1430 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

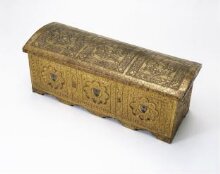

By about 1300, the cassone, or chest, was the most prestigious form of storage in Italian households. It was often associated with marriage or becoming a nun. This example is inscribed with the opening lines of the Nicene Creed, a statement of belief in the Christian faith. The inscription is written in a mixture of Latin and Italian. This mixed language was used during the Middle Ages in the popular religious texts presented to girls about to be married or enter a nunnery. This chest dates from about 1400. However, the coat of arms was almost certainly added in the 19th century, to give the chest greater romance and prestige. The coat of arms is that of the Chigi family, who acted as bankers to Pope Julius II (1443–1513).

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Pinewood with gilt gesso decoration |

| Brief description | Italian (Sienese) 15th century |

| Physical description | Rectangular box with arched lid, covered on all sides bar the back with gilded and moulded gesso, the outlines of which have been liberally punched. The Cassone is decorated with a series of Gothic multifoil roundels, three each on the lid and front, and one each on the sides. The front is inscribed with the Nicene Creed, and emblazoned with coats of arms that resemble those of the Chigi family of Siena. The arched lid of the cassone is decorated with three square panels, each containing a double-rimmed gothic multifoil roundel, and each bordered with frames containing four symmetrical scroll patterns and a concave diamond in all four corners. A star is placed within the curve of each multifoil, and in the centre of each roundel is a gilt disc decorated with black dots and set in a square frame with concave sides within two concentric rings. Gilt discs, decorated with black dots and surrounded by punched scroll patterns, are placed in the corners between the roundels and the borders. The narrow spaces between the panels are made up of strips of punched diamond patterns, with a ring in the centre of each one. The outer edges of the lid are decorated with punched lunettes each with five punched spokes terminating in small lilies. The front and side lips of the lid is decorated with a frieze of gilded dragons, of built up gesso and punched edges, facing each other either side of a gilded disc with five black dots arranged in a cruciform pattern. The front of the cassone is made up of three dished gothic multifoil roundels, each framed with a square border, inscribed with the opening lines of the Nicene Creed in Italian Gothic script. The curves of the central roundel are filled with sprigs of clover, and those of the two side roundels with stars. All three roundels have a shield placed in a circular frame in the middle. The coat of arms – a dark green star above three rounded rocks on a silver background - is repeated on each shield at the side, as well as all three on the front. The corners between the roundels and the ‘Nicene Creed’ borders of each panel are filled with winged dragons. The two narrow spaces between the three panels are filled with winged seraphim, and those at both ends with Salamonic columns, flanked with strips made up of spoked lunettes, similar to those on the lid. Beneath the panels is a gilt strip with a punched zigzag frieze and alternating triangles made from larger punches. There are five gilt bracket feet, flush with the front, decorated with winged creatures and other ornaments, and two on each side. Both sides are decorated with a single octofoil roundel, with stars placed inside the curves, and bordered with frames similar to those on the lid. The spoked lunette friezes are repeated on the side and base edges. The back is roughly painted with two rows of ten blank shields each on a black background. The cassone is held together by dovetail joints reinforced with nails, supplemented by later screws. At a much later date small rectangular blocs were screwed on the left side and nailed along the front and right side to the feet. Huge nails fix the feet and base plank to the bottom edges of the sides and front of the cassone, and a strip of wood to the bottom edge of the back. The base plank is reinforced with a centrally placed cleat, nailed to the bottom edge of the back and slotted into a groove of the front central foot. The front, back and sides are joined to each other with dovetail joints, visible on the back of the cassone. The lid is joined to the rest of the structure with staple hinges. Lunettes made up of more recent pieces of wood form the side edges and lips of the lid. The floor, sides, back and front are each made up of one piece of wood, and the lid is made from one piece of cooped wood, that has subsequently split. The right and front feet are old, whereas the left foot, side edges and lips are relatively recent replacements. The lid is probably a later replacement – one long narrow split on the inside, and the smooth, unworn, metallic decoration on the outside of the lid both suggest that this is a later date. However, feint punch marks and leaf patterns on the left sides of the cassone indicate earlier work. The gilding and punch work on the exterior seem to be of relatively recent work, and not sufficiently worn. Traces of earlier red paint or possibly bole and gesso have been found on the right side, and only small fragments of gilding on the bottom left section of the left roundel at the front. On the left side are feint traces of earlier versions of the spoked lunette decoration and lef motifs. The coats of arms are painted Prussian Blue, a colour invented in about 1715, and no traces of earlier emblems have been found during x-ray examinations. It has been noted that the Prussian-blue hue is found on items acquired by the National Gallery from William Blundel Spence. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Production type | Unique |

| Marks and inscriptions | CREDO IN UNU DEO PATRE ONIPOTENTE FATORE CIE/ E TEPA ED IVISIBILIO ONIO ED IN UNO DOMINO CIESO CRI / ISTO FILIU DEI UNICI ED ILIU ED ES PATRE NATO ANTE ONIA Note Decoration; Latin; Gothic; front panel; moulding; gesso Translation I believe in one God the omnipotent father, maker of heaven/ and earth and all things visible and invisible and in one lord Jesus Christ/ the only begotten son of God, begotten of his Father before all things |

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | Bought for 18l (No further information in register): 'COFFER. Carved and gilt all over, with armorial shields, and a portion of the Nicene Creed in Latin. Italian. 16th cent.y H.2 ft., L. 5 ft. 3 in., W. 1 ft. 10 1/4 in. Bought 18l' See also Conservation report 2003. The chest was acquired in 1862 for £18. No further information is supplied on early registers. However, the South Kensington Museum was actively purchasing from dealers based in Florence during this period, and William Blundel Spence, an English artist and dealer, is a possible candidate. According to W.Hunergford Pollen (Specimens of Ancient and Modern Furniture, p. 126) 'The gilding has been retouched, perhaps wholly redone. The chest has been used for a sacristy or private domestic chapel for holding ecclesiastical vestments.' Traces of earlier punch marks can be discerned, but there seem to be almost no traces of earlier gilding (see physical description). It is thought that the cassone was gilded not long before it was purchased by the South Kensington Museum. |

| Historical context | On Gilded chests [from P.K.Thornton, The Italian Renaissance Interior 1400-1600 (London 1991), p.196] 'A far more important form of decoration was gilding. This was executed on a gessoed ground but the most costly chests embellished in this way had patterns in relief that were cast in moulds and applied to the ground prior to gilding. Some of this work is exquisite; it is so delicate that there can be no doubt that such chests were primarily for show. [note 27 Schiaparelli* has much of great interest to say about gilded cassoni (see pp. 257-62) including the fact that some 'gilding' was executed with tin-leaf instead of gold-leaf: it was presumably covered with a yellow varnish to make it look like gold. This was a cheap method. Cennino Cennini, in his Trattato della pittura, written in the 1390s, explains how to gild chests which he said, should be treated in the same way as the gilding on paintings. He also tells one how to make moulds for applique relief ornament.] Although very costly, such chests were made in sufficient numbers in Venice (and probably in other cities) to cause the authorities to try and ban the 'making and using' of chasse dorate in a sumptuary regulation of 1489. [note 28 Bistort*, p. 370] Although much relief ornament was shallow and delicate, some Florentine cassoni bear large figures, almost as tall as the fronts of the chest. Figures on this scale offered scope for excellent sculptors and Vasari even credited the young Donatello with having executed Fighure di relievo on a cassone. Donatello did no such thing, it now seems, but the fact that Vasari could make such a claim is an indication of the high quality the relief ornament on these chests could possess. [note 29 Schiaparelli*, p. 262. See also Vol. II, p. 74, n. 150.] Painted decoration was always present in some measure on gilded chests; it could be limited to a small coat of arms that is almost lost in the surrounding sea of gold; at the other end of the scale it could form the sort of large storiated panel already discussed. It should here be remembered that the gilded areas may have cost at least as much to execute as the painted parts and sometimes much more (p. tot). In the fifteenth century the two processes were usually carried out in the same workshop; this was certainly the case with Apollonio di Giovanni's workshop in Florence.' Comparable chests *V&A London (museum No. 247-1894), H 20 1/2", L 5 ft. 1/2", depth 20 1/2" (52 x 154 x 52cm) , bought in Rome. *Cassone in the Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection on loan to the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. HWD: 65.5 x 164.5 x 58cm; ex coll. Saulmann, Florence, and coll. Murray. The gilding attributed to Giusa di Frosino, and painting attributed to Benedetto di Bindo (documented in Siena 1411-Perugia 1417), early 15th century; published in Patricia Lurati, Doni nuziali del Rinascimento nell collezioni svizzere, (Locarno: Armando Dadò Editore, 2007) no. 14 *Danske Kunstindustrimuseum inv. B28/1925, Copenhagen. HWD: 67 x 162 x 56cm Illustrated in Frieda Schottmüller, Furniture and Interior Decoration of the Italian Renaissance (Stuttgart, 1928), fig. 84); ex. collection of Camillo Castiglioni II, bought Amsterdam 1925. [This is probably the chest referred to by Schubring fig. 51 and Supplement no.899, as 'A later variant' of a chest in Böhler's Collection - formerly in the Miller von Aichholz Collection, later C. Castiglioni, Auction Catalogue no. 151] *Prince of Liechtenstein Collection, formerly in Vienna (Schloss Valuz, Liechtenstein) inv. No. S 779 with the opening lines of SALVE REGINA. Published in Schubring, Cassoni; Truhen and Truhenbilder der Italienischen Frürenaissance, ein Beitrag zur Profanmalerei im quattrocento (Leipzig: Karl W. Hiersemann, 1915). Lurati (see above) notes that the sides display the badge of the Ospedale di Santa Maria della Scala (Siena). Acquired from Stefano Bardini of Florence in Florence in 1896. *Museo d'Arti Applicate, Milano, HWD: 63 x 154 x 53cm with inscription IPSE AUTEM TRANSIENS PER MEDIUM ILLORUM IBAT (Luke 4.30); SI ERGO ME QUAERITIS SINITE (H)OS AB IRE (John 18.8); ASPICE MORTALIS PRO TE DATUR (H)OSTI (source unidentified). See Enrico Colle, Museo d'Arti Applicate: Mobili e intagli lignei (Milan, 1996), no. 151; attrib. Siena mid-15th century, but possibly largely 19th century. *An Italian Painted and Pastiglia Cassone inscribed 'pater noster...' , Siena, mid 15th century, HWD: 60 x 162 x 56cm; sold Sothebys, Haute Epoque, 31/10/2006 *Cassone from the Bardini Collection, published in William M. Odom, A History of Italian Furniture (New York, 1918), fig. 13 * Cassone auctioned 1924 by Tollentino (cat. 766), see Lurati p.122 * Cassone at Palazzo Publico (Siena) attributed on a documentary basis to Taddeo di Francesco and Giusa di Frosino, dated c1400-10; see Lurati p.122 Lurati, see above 2007, provides the most considered assessment of this group of gilded chests. She refers to Pope-Hennessy (1939) as the first to suggest a connection between sacristy frescoes in the Duomo di Siena (generally attributed to Taddeo di Bartolo) and painted roundels on cassoni. In 1991 Freuler developed the thesis of stylistic and iconographic similarities between the cassone medallions and the Creed panels by Benedetto di Bindo (Museo dell’Opera del Duomo di Siena), proposing that the Madrid cassone may have been commissioned c1411-12 for the Siena duomo by the Augustinian canons of Siena who cherished the Nicene Creed, and that it may be attributed to Giusa di Frosino and Benedetto di Bindo. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Literary reference | Nicene Creed |

| Summary | By about 1300, the cassone, or chest, was the most prestigious form of storage in Italian households. It was often associated with marriage or becoming a nun. This example is inscribed with the opening lines of the Nicene Creed, a statement of belief in the Christian faith. The inscription is written in a mixture of Latin and Italian. This mixed language was used during the Middle Ages in the popular religious texts presented to girls about to be married or enter a nunnery. This chest dates from about 1400. However, the coat of arms was almost certainly added in the 19th century, to give the chest greater romance and prestige. The coat of arms is that of the Chigi family, who acted as bankers to Pope Julius II (1443–1513). |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 7815-1862 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 28, 2002 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest