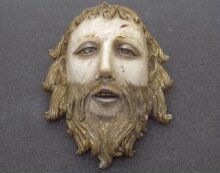

Head of St John the Baptist

Panel

1470-1490 (made)

1470-1490 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Saints are the heroes and heroines of Christian faith. In the 14th and 15th centuries, they were a popular subject for alabaster carvings. Religious themes penetrated private life, so devotional images of saints were sculpted not only for church interiors, but also for individuals to contemplate within the privacy of their homes. English carvings of John’s head alone are rare. This piece must have been a special order for a rich client. The wound on John’s left temple, beneath his gilded locks, alludes to the story that when his head was presented to Herod’s wife Herodias, she struck it with a knife.

There are two sorts of alabaster. Calcite alabaster is very hard and was used in ancient times. This object is made of gypsum alabaster which is a fine-grained, soft and smooth stone. Although at first glance it looks a little like marble, which it was intended to imitate, it was much easier to carve due to its softness, and alabaster objects were therefore significantly cheaper to produce. Marble does not originate in England, so it was imported if needed.

The carving of alabaster, mostly quarried in Tutbury and Chellaston near Nottingham, took on industrial proportions in England between the middle of the 14th and the early 16th centuries. The market for altarpieces and smaller devotional images was a large one. It included not only religious foundations but also the merchant classes. Many hundreds of English alabasters were exported, some as far afield as Iceland and Santiago de Compostela in north-west Spain.

There are two sorts of alabaster. Calcite alabaster is very hard and was used in ancient times. This object is made of gypsum alabaster which is a fine-grained, soft and smooth stone. Although at first glance it looks a little like marble, which it was intended to imitate, it was much easier to carve due to its softness, and alabaster objects were therefore significantly cheaper to produce. Marble does not originate in England, so it was imported if needed.

The carving of alabaster, mostly quarried in Tutbury and Chellaston near Nottingham, took on industrial proportions in England between the middle of the 14th and the early 16th centuries. The market for altarpieces and smaller devotional images was a large one. It included not only religious foundations but also the merchant classes. Many hundreds of English alabasters were exported, some as far afield as Iceland and Santiago de Compostela in north-west Spain.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | Head of St John the Baptist (generic title) |

| Materials and techniques | Carved, painted and gilt alabaster |

| Brief description | Panel, alabaster, depicting the head of St John the Baptist, English, 1470-1490 |

| Physical description | The head of St. John the Baptist is represented with curly beard and hair in curls on his forehead and in three curled locks on each side. The upper lip is clean-shaven and the mouth is open. Eyelids and teeth are carved. There is a wound on the saint's left temple. The top of the nose is chipped. The hair and beard are gilded. The eyes and mouth and the wound are painted, with trickles of blood running down from the wound. The back of the head has four holes, none of which looks original. According to Hildburgh 1928, when it arrived in his collection the head had brownish overpaint on the hair, and two pieces of lead inserted in the central part of the moustache, painted to simulate hair. These were removed and the indentation filled with wax. He also suggests that some of the paint (eg the bluish lips, the trickles of blood) were added in Spain. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Credit line | Given by Dr W. L. Hildburgh FSA |

| Object history | Previously in Spain the relief was acquired by Dr W. L. Hildburgh in Paris. On loan from him since 1926. Given by Dr Hildburgh in 1946. |

| Historical context | Heads of St John the Baptist in alabaster were very popular in late medieval England - more than 90 examples survive which vary from a simple image of the saint's head like this example, to more complex iconographic groups showing the head surrounded by other saints, angels, the Virgin, Christ etc. The heads were a feature of many English domestic interiors, as can be seen in inventories from approx. 1480-1540. It is likely that single heads like this example were sometimes displayed on wooden, alabaster or even silver platters, mirroring the saint's story. A number of inventories refer to a 'St John's cloth', presumably used to cover the image when it was not in use. Six surviving images of St John's head are contained in wooden tabernacles, but none of these depicts only the head, as with this object. The subject emerged from the story of Herod, whose wife's daughter, Salome, asked for the head of the saint on a platter. The image of the saint's head appears in Byzantine illumination by the eleventh century, and spread thoughout Europe, largely through veneration of a famous relic at Amiens. The iconography was particularly popular in Germany, where it is known as the 'Johannesschüssel' (see Arndt and Kroos, 1969 for examples). Images of a similar type to this V&A example were produced in stone and wood in 15th-century Westphalia, and the subject was further developed by the English alabaster industry at a similar date. Devotion to the saint was popular amongst guilds as well as individuals (Marks and Williamson (eds), Gothic: Art for England, 2003, cat. no. 348). In the diocese of Norwich alone, there were 120 guilds with St John as their patron in the Middle Ages. Heads of this type are therefore likely to have been owned and used in a guild context, as well as for private devotion. |

| Production | In spite of its Spanish provenance, the head is not Spanish. It has been discussed in relation to German heads (eg Hildyard 1937), but most commentators agree on an English origin. Cheetham points out several details which would support this: the treatment of the hair and beard, with the shaven upper lip which is found on other English St John's heads; the wound above the left eye, a common feature on English examples; and the alabaster stone itself, which looks English rather than continental. But as he points out, the carving is not at all typical of English alabaster work, and so may represent a special order for a wealthy client. Dated by Balogh 1963 and Cheetham 1984 to late fifteenth century. |

| Subject depicted | |

| Summary | Saints are the heroes and heroines of Christian faith. In the 14th and 15th centuries, they were a popular subject for alabaster carvings. Religious themes penetrated private life, so devotional images of saints were sculpted not only for church interiors, but also for individuals to contemplate within the privacy of their homes. English carvings of John’s head alone are rare. This piece must have been a special order for a rich client. The wound on John’s left temple, beneath his gilded locks, alludes to the story that when his head was presented to Herod’s wife Herodias, she struck it with a knife. There are two sorts of alabaster. Calcite alabaster is very hard and was used in ancient times. This object is made of gypsum alabaster which is a fine-grained, soft and smooth stone. Although at first glance it looks a little like marble, which it was intended to imitate, it was much easier to carve due to its softness, and alabaster objects were therefore significantly cheaper to produce. Marble does not originate in England, so it was imported if needed. The carving of alabaster, mostly quarried in Tutbury and Chellaston near Nottingham, took on industrial proportions in England between the middle of the 14th and the early 16th centuries. The market for altarpieces and smaller devotional images was a large one. It included not only religious foundations but also the merchant classes. Many hundreds of English alabasters were exported, some as far afield as Iceland and Santiago de Compostela in north-west Spain. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | A.79-1946 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | November 18, 2002 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest