Cup

ca. 1560 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This cup was used in Protestant worship to serve the consecrated wine during Holy Communion.

During the Reformation there was a return to a simpler, more direct form of worship. Protestants rejected the Roman Catholic belief in 'transubstantiation', in which the bread and wine are miraculously transformed during the Mass into the body and blood of Christ, and proposed instead a symbolic service of shared communion. In this, the congregation would regularly take wine as well as bread, whereas before they had been chiefly spectators.

To consolidate this break with traditional religion, the church authorities launched a programme from about 1560 to replace the 'old massing chalices' with 'decent' communion cups of prescribed design. The design of this cup, however, looks back to those of the late 1540s, when reformers were anxious to have proper communion vessels but had not yet devised an official style. It is unusually heavy, which suggests it was made from the metal of several pre-Reformation pieces.

During the Reformation there was a return to a simpler, more direct form of worship. Protestants rejected the Roman Catholic belief in 'transubstantiation', in which the bread and wine are miraculously transformed during the Mass into the body and blood of Christ, and proposed instead a symbolic service of shared communion. In this, the congregation would regularly take wine as well as bread, whereas before they had been chiefly spectators.

To consolidate this break with traditional religion, the church authorities launched a programme from about 1560 to replace the 'old massing chalices' with 'decent' communion cups of prescribed design. The design of this cup, however, looks back to those of the late 1540s, when reformers were anxious to have proper communion vessels but had not yet devised an official style. It is unusually heavy, which suggests it was made from the metal of several pre-Reformation pieces.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Silver, raised and stamped |

| Brief description | Silver, London, ca. 1560, probably by Robert Talyboyes |

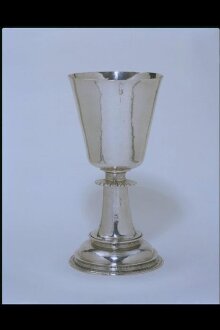

| Physical description | Silver communion cup, with bucket-shaped bowl on a cylindrical stem flaring to the round domed foot which bears bands of stamped decoration. Near the top of the stem is a flat petalled knop beneath a band of stamped decoration. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | Maker's mark, probably of Robert Taylboyes, double struck on rim: a stag's head |

| Gallery label | Communion Cup

This cup was used in Protestant worship to serve the consecrated wine during Holy Communion.

During the Reformation there was a return to a simpler, more direct form of worship. Protestants rejected the Roman Catholic belief in ‘transubstantiation’, in which the bread and wine are miraculously transformed during the Mass into the body and blood of Christ, and proposed instead a symbolic service of shared communion. In this, the congregation would regularly take wine as well as bread, whereas before they had been chiefly spectators.

To consolidate this break with traditional religion, the church authorities launched a programme from about 1560 to replace the ‘old massing chalices’ with ‘decent’ communion cups of prescribed design. The design of this cup, however, looks back to those of the late 1540s, when reformers were anxious to have proper communion vessels but had not yet devised an official style. It is unusually heavy, which suggests it was made from the metal of several pre-Reformation pieces.

London, England, about 1560; probably by

Robert Taylboyes (active about 1551–80)

Silver

Museum no. M.161-1951. Given by Henry Whittaker(22/11/2003) |

| Credit line | Given by Henry Whittaker |

| Historical context | The Reformation in England On the eve of the Reformation, churchgoing in England was a colourful, sensory experience, rich in ceremony. In the 1530s, however, Henry VIII threw off the authority of the pope. Under his successor Edward VI (reigned 1547-53) major changes in worship and church decoration were introduced. English Reformers wanted a return to a simpler, more direct form of worship. Their boldest move was to reject the Roman Catholic belief in 'transubstantiation', in which the bread and wine are miraculously transformed during the Mass into the body and blood of Christ. They proposed instead a symbolic service of shared communion, conducted in interiors stripped of distracting furnishings and images. The congregation would play an active role in the communion, regularly taking wine as well as bread, whereas before they had been chiefly spectators. Crown commissioners confiscated or destroyed much of the goldsmiths' work of the medieval church. Some parishes concealed or sold their silver before the commissioners arrived, but by the early 1550s, many were left with just a single cup and paten. Some churches had no precious metal at all. Consolidation The success of the Reformation by 1600 owed much to an ingrained culture of obedience to the crown. During the brief reign of Mary I (1553-8) England returned to Catholicism, but under Elizabeth I it swung back to Protestantism, spurred on by state propaganda that Catholicism represented a political threat. Even so, this rupture with the past met with quiet resistance as many people were attached to the old faith and its trappings. To consolidate this break with traditional religion, the church authorities launched a programme from about 1560 to replace the 'old massing chalices' with 'decent' communion cups of prescribed design. This gave a massive boost to the goldsmiths' trade and the great demand led to the formal establishment of assay offices outside London, at Chester, York, Norwich and Exeter. About 2000 communion cups from the period survive. |

| Summary | This cup was used in Protestant worship to serve the consecrated wine during Holy Communion. During the Reformation there was a return to a simpler, more direct form of worship. Protestants rejected the Roman Catholic belief in 'transubstantiation', in which the bread and wine are miraculously transformed during the Mass into the body and blood of Christ, and proposed instead a symbolic service of shared communion. In this, the congregation would regularly take wine as well as bread, whereas before they had been chiefly spectators. To consolidate this break with traditional religion, the church authorities launched a programme from about 1560 to replace the 'old massing chalices' with 'decent' communion cups of prescribed design. The design of this cup, however, looks back to those of the late 1540s, when reformers were anxious to have proper communion vessels but had not yet devised an official style. It is unusually heavy, which suggests it was made from the metal of several pre-Reformation pieces. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | M.161-1951 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | September 27, 2002 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest