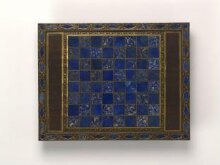

Games Board

ca. 1570-90 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This board has a chess board on one side, and half a back-gammon board on the other. It would have formed one half of a 16th-century 'pair of tables', with another, similar board, completing the back-gammon board and providing (on its reverse) a board for Nine men's morris, a game of alignment.

The three patterns of blue lapis lazuli used probably came from Afghanistan, and were known in the 16th century as 'Persian lapis lazuli'. The gilded decoration of delicate moresque ornament is painted on rich veneers of tropical hardwood. It was particularly fashionable in Venice 1560-1600 for a wide range of luxury products from musical instruments to bookbindings, small boxes and mirror frames. The taste in Venice (and nearby Padua) for Moresque ornament was probably first inspired during the 1470s by Islamic book bindings imported from cities in Turkey, Egypt, Persia and Syria.

The three patterns of blue lapis lazuli used probably came from Afghanistan, and were known in the 16th century as 'Persian lapis lazuli'. The gilded decoration of delicate moresque ornament is painted on rich veneers of tropical hardwood. It was particularly fashionable in Venice 1560-1600 for a wide range of luxury products from musical instruments to bookbindings, small boxes and mirror frames. The taste in Venice (and nearby Padua) for Moresque ornament was probably first inspired during the 1470s by Islamic book bindings imported from cities in Turkey, Egypt, Persia and Syria.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Veneered with tropical hardwood (probably rosewood), and lapis lazuli, with gilded decoration |

| Brief description | Rosewood and gilding with lapis lazuli; Venice c1570-90 |

| Physical description | A games board, the carcase wood (unidentified) veneered with a tropical hardwood (rosewood or ebony) with gilt moresque decoration, and inlaid with three colours of lapis lazuli: a darker shade with gold veining, a pale shade with speckling, and a blue/white marbled shade. The rigid board with plain edge veneers, is mitred at the corners. On front and back is a raised border inlaid with 36 alternating ellipse and elongated diamonds (edged with gilding), with a disc at each corner, all in two colours of lapis lazuli, with a cavetto 'sight-edge' moulding with gilded bead and reel, the ground with scrolling floral moresque ornament. There is no evidence of edge fixings, where another board was fixed to this one. One side of the board is laid out for back-gammon with 14 points of alternating lapis lazuli, defined by hardwood veneer the ground with gilded moresque ornament and a central rectangle with plain gilded border containing gilt moresque ornament in a symmetrical pattern. The veneer used appears to have been a single large sheet cut to shape, although numerous splits have opened up. The other side of the board is laid out for chess with 64 squares of alternating lapis lazuli veneers with narrow hardwood dividers with gilded stringing, surrounded on all four sides by a narrow border with floral scroll ornament gilded, and enclosed at both ends with a plain compartment (presumably for captured chess men) which is edged with gilded stringing. The veneers appear to be four sections: two narrow edge pieces, and two wider end pieces. Condition The hardwood veneer split in numerous places. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Bequeathed by the 6th Duke of Wellington |

| Object history | Bequeathed by (Gerald), 7th Duke of Wellington, Stratfield Saye House, Reading, Berks. RF 72/2367 Described in correspondence as "chess and backgammon board and stand", but the no more detailed reference to a stand is on the RF nor further information on the history of the board. Sold from the Spitzer collection no. 2988, Paris 17/4/1893 Bought at auction Sotheby's 5th May 1938, lot 87 ('The property of Mrs. Wilfrid Buckley (decd.)) This board forms half of a typical 16th century 'pair of tables' for games. Another board half would have completed the backgammon board with larger merels (nine men's morris) on the reverse. However, there is no evidence of hinging on W.9-1972, perhaps because the weight of the boards would have put undue strain on the hinges, so it may be assumed that the pair, though used together were not physically joined. The attribution to Venice, an established centre for the production of luxury artefacts in the 16th century, rests in large part on the painted decoration of gilt moresques (see below). Although similar gamesboards with hardstone and painted moresque ornament have not been identified, the combination on Venetian luxury objects c.1550-1600 of hardstone and painted moresque suggests that a Venetian origin for this board is likely. This gamesboard may be considered as a product of the late 16th century Venetian interest in what was known as Persian style decoration. There is certainly a neat congruence between the use of 'Persian lapis lazuli' and gilded moresque decoration 'in the Persian style'. The likely design of the gamespieces that would have accompanied the board remains a matter for speculation; possibly they would have been cut and carved in hardstone or tropical hardwood, like the veneers and mouldings used on the board. Lent to the exhibition Lapis Lazuli – Magical Blue, Museo degli Argenti, Florence, 9 June – 11 October 2015 |

| Historical context | "Lapis lazuli is characterised by its intense deep-blue colours, and by specks of tiny, sometimes auriferous pyrite crystals that create a sparkling effect. Some less pure varieties have white or grey specks due to the presence of calcareous matter. Although less valuable, these varieties were useful in decorative hardstone work. During the renaissance the most intense and uniformly coloured variety came from Badakshan in Afghanistan and was called 'Persian lapis lazuli'. Other, more speckled varieties were obtained in France (and from the end of the eighteenth century Russia became the main exporter to Europe)." (Taken mainly from Anna Maria Giusti: Pietre Dure - Hardstone in Furniture and Decorations. (London, 1992), p. 270) "Because for centuries Venice was the main European port of entry for exotic hardstones from the Orient, it is not surprising that La Serenissima - the Republic of Venice - has a long history of hardstone cutting. The hardstone carvers' guild was established there in 1284, only slightly later than the one in Paris. Regulations for the craft followed in 1318 and were enforced. Venetian luxury goods flooded into the northern states of Italy and encouraged the growth of the industry, not only there but also in much of Europe. ...The.. lapis lazuli from Afghanistan [was] either brought west along Ottoman trade routes that ended in Venice or were spoils from Byzantium." Koeppe notes, in relation to a late 16th century Venetian cabinet inset with lapis lazuli and various hardstones, and partly gilded with arabesques, that the combination of carefully chosen semiprecious stones (naturalia) and the elegant design and fine craftsmanship of the wooden structure, decorated with sparkling gold paint and arabesques (arteficialia), was particularly appropriate to a collector's curiosity cabinet. NEW YORK, Metropolitan Museum, Wolfram Koeppe and Annamaria Giusti (eds.): Art of the Royal Court. Treasures in Pietre Dure from the Palaces of Europe. (New York, New Haven, 2008), cat. no. 21, p. 142 [A collector's cabinet]. [See also NEW YORK, Metropolitan Museum, Stefano Carboni (ed.), Venice and the Islamic world, 828-1797, (New York, New Haven, 2007)] For discussion of this type of painted decoration, see Huth, Hans: Lacquer of the West. The History of a craft and an industry, 1550 - 1950. (Chicago, 1971), chapter 1; Peter Thornton, Form and Decoration (London, 1998), chapter 3; Alberici, Clelia: Il Mobile Veneto (Milan, 1980), p.61ff.; Anna Contadini 'Middle-Eastern objects' in At Home in Renaissance Italy, eds.Marta Ajmar-Wollheim and Flora Dennis (London, 2006), p308ff.; Ernst J. Grube "Venetian lacquer and Bookbindings of the sixteenth century." in New York, Metropolitan Museum, Stefano Carboni (ed.), Venice and the Islamic world, 828-1797, (New York, New Haven, 2007), pp. 230-43 "Fine lacquerwork was made in Persia during the 16th century. It was commonly decorated with moresques executed in gold: this was done on relatively small items, such as folding book-rests, book-covers, containers for writing materials, etc. Such objects excited the admiration of Europeans whenever they saw them, and early imitations of this work embodying moresque decoration were made in Venice. The technique was deemed suitable for embellishing the covers of highly important government documents, so apparently carried no light-hearted or frivolous connotation in the way that imitations of Chinese artefacts were often to do later. Venetian lacquer was also used for making small objects, such as jewel caskets covered with moresques, although entirely occidental figure-subjects occasionally occupy panels within the imitation Islamic ornament. Sometimes the ground of the panels in such work was made of mother-of-pearl which reflects light back through the painted deocration applied on to it. A similar effect was contrived with a gold ground over which painted decoration was applied; the colours were often applied so as to form ‘the ground’, leaving the pattern itself unpainted (reserved as it is called).. exemplified on the V&A ‘Queen Elizabeth virginals’ (about 1570) or a harp ordered for the private orchestra of Duke Alfonso d’Este (1581, Rome)." Thornton pp.34-5 Huth says that from the 13th century Venice had been an entry point to Europe for goods (earthenware, metalwork, textiles, jewelry and lacquerware) from the Levant and Orient [sic]. A Venetian document of 1283 consists of rules for the depentores (those working with a brush, involved in the production of varnished caskets, tables and woodwork). The decoration of wares as opposed to simply protecting them with varnishes seems to have begun during the mid 16th century. A Syrian craft which may have inspired Venetian artisans working in lacquer was the practice of damascening metal, known in Milan and Venice as early as 1300. The Italian craftsmen (no non-European craftsmen were supposed to reside in Venice) who practised this art were called azziministi. Another non-European craft introduced to Venice from the late 15th century was the practise of fashioning elaborate bindings for books. Venetian copies or adaptations of lacquered bindings ‘in the Persian style’ date from the middle of the 16th century (eg Binding, Museo Correr 1570-77). European engravings based on Moresque designs, such as those by ‘the Master F’, were circulating in Italian workshops as early as 1520. Venetian shields of wood covered with parchment, painted with knotwork and scrolls, and with areas in white, red and green that shone through the varnish, giving the effect of lacquer survive in armeria of the Doge’s palace (Venice ) and from the household of the Bishop of Salzburg. Huth discusses other types of object (probably Venetian) with similar decoration, which may have been what was referred to by Italians variously as ‘frissi grottesche’, ‘alla zemina’ in the Persian manner, ‘petteniera turchesca’ in the Turkish manner: a quiver case, a folding table, small cases (casse da pettenti), caskets (scrigni or possibly what was known as ‘casse da conzar il cao’, boxes for dressing the hair), mirror frames and frames of architectural form with or without inset marble plaques, cuoridoro shields (described by Contadini in At Home in Renaissance Italy eds. Ajmar-Wollheim, and Dennis, pp.319-321), cabinets with leather coverings and musical instruments such as harpsichords and harps. Most relevant to discussion of the V&A gamesboard is a group of various frames (which Huth describes as Venetian c.1580) of architectural form survive, with inset marble slabs, and with black/gold moresque patterns on the cornices and mouldings (pl.14-19). Some frames of this type are incorporated into table cabinets. |

| Summary | This board has a chess board on one side, and half a back-gammon board on the other. It would have formed one half of a 16th-century 'pair of tables', with another, similar board, completing the back-gammon board and providing (on its reverse) a board for Nine men's morris, a game of alignment. The three patterns of blue lapis lazuli used probably came from Afghanistan, and were known in the 16th century as 'Persian lapis lazuli'. The gilded decoration of delicate moresque ornament is painted on rich veneers of tropical hardwood. It was particularly fashionable in Venice 1560-1600 for a wide range of luxury products from musical instruments to bookbindings, small boxes and mirror frames. The taste in Venice (and nearby Padua) for Moresque ornament was probably first inspired during the 1470s by Islamic book bindings imported from cities in Turkey, Egypt, Persia and Syria. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | W.9-1972 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | August 2, 2001 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest