The Theewes Claviorgan

Claviorgan

1579 (made)

1579 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Object Type

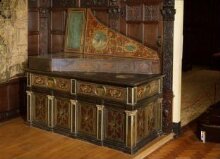

A claviorgan was fitted with strings as well as organ pipes. This example has lost almost all of these, though the soundboard, case and harpsichord stops still survive. Hardly any historic claviorgans are extant, but they were fairly widespread during the 16th century and a number were owned by Henry VIII.

People

This claviorgan was made in London by Lodewyk Theewes. He was a native of Antwerp in Flanders (now Belgium) and settled in London in the parish of St Martin-le-Grand, becoming naturalised in 1567.

Time

Signed and dated 1579, this claviorgan is the earliest surviving keyboard instrument to be made in Britain. It is painted according to the fashions of the time. The case is decorated with marbling and strapwork, the lid with monkeys and Orpheus playing to the beasts, a popular classical theme. The monkeys are derived from engravings of about 1550 by the German printmaker Virgil Solis (1514-1562). Furniture of this date is was often brightly coloured, but little of this decoration has survived. Prized in the 16th century, the claviorgan was more of a curiosity by 1660, when Samuel Pepys called it 'but a bawble with a virginall joining to it'.

Place

Before the claviorgan entered the collections of the V&A in 1890, it had long stood in the chapel of Ightham Mote, Kent. The house has no known connections with the families whose coats of arms decorated the instrument.

A claviorgan was fitted with strings as well as organ pipes. This example has lost almost all of these, though the soundboard, case and harpsichord stops still survive. Hardly any historic claviorgans are extant, but they were fairly widespread during the 16th century and a number were owned by Henry VIII.

People

This claviorgan was made in London by Lodewyk Theewes. He was a native of Antwerp in Flanders (now Belgium) and settled in London in the parish of St Martin-le-Grand, becoming naturalised in 1567.

Time

Signed and dated 1579, this claviorgan is the earliest surviving keyboard instrument to be made in Britain. It is painted according to the fashions of the time. The case is decorated with marbling and strapwork, the lid with monkeys and Orpheus playing to the beasts, a popular classical theme. The monkeys are derived from engravings of about 1550 by the German printmaker Virgil Solis (1514-1562). Furniture of this date is was often brightly coloured, but little of this decoration has survived. Prized in the 16th century, the claviorgan was more of a curiosity by 1660, when Samuel Pepys called it 'but a bawble with a virginall joining to it'.

Place

Before the claviorgan entered the collections of the V&A in 1890, it had long stood in the chapel of Ightham Mote, Kent. The house has no known connections with the families whose coats of arms decorated the instrument.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 41 parts.

|

| Title | The Theewes Claviorgan (popular title) |

| Materials and techniques | Painted oak, with spruce soundboard, and embossed paper lining |

| Brief description | Claviorgan, 1579, English, Lodewyk Theewes |

| Physical description | Materials Organ: painted and gilded oak; harpsichord: spruce soundboard and poplar(?) for the internal structure, tempera painting on the soundboard (the rosette missing), tooled and gilded leather and embossed paper lining (originally gilded) Design The claviorgan consists of a harpsichord with hinged lid inset on the top of a rectangular, panelled organ case which is articulated with Ionic pilasters below a frieze, and which is fitted (below the keyboard) with a hinged door under the fixed frieze. The organ chest below is divided unequally into two sections. The organ pipes were in the smaller middle (or frieze) section just below the harpsichord and the bellows were in the larger bottom section. The three decorated sides of the organ case are thinly oil painted on an off-white ground, in a scheme of red, green, white, stone colour and gold – with strong emphasis on marbling – and with some green glaze. The framing elements simulating black marble with gilded capitals (with carved flower heads) and mouldings, the panels with stone-coloured strapwork on an ochre background, and on the frieze panels, four roundels bearing painted coats of arms (for Anthony Roper, previously overpainted with those of Sir Edward Hoby and Margaret Carey, and removed in 1947). The top is painted with similar strapwork, with two roundels, one large and one small, both now too worn to be legible. Despite numerous areas of retouching the scheme retains large areas of what appears to be original paint, and some gilding. The outside of the harpsichord is covered with brown calf-leather tooled with concentric rectangles, probably originally red with green framing. The inside of the harpsichord is decorated as follows: the key well with traces of gilded moulded paper ornament with romaine heads, strapwork and precious stones (more surviving inside the case on the top edge of the nameboard and the jackrail) and a painted rope pattern border; the soundboard is painted in tempera with a wide range of flowers, identified by Rose (2002) as dog-rose, four other varieties of rose, borage, carnation, lily of the valley in flower and in berry, dianthus, lesser spearwort, cornflower, pansy, columbine, stock, periwinkle, wallflower, fleabane, marigold, geum, anemone, and a pair of cherries; the underside of the lid (which consists of a keyboard flap, and two sections) is painted with a rectangular panel, now blue-green (flap), a similar larger panel with a strapwork border bearing the maker’s inscription, and two large cartouches set within elaborate strapwork, with shadowing, fictive fixing holes, ribbons, festoons, precious stones, flaming grenades, winged snakes, and monkeys deriving from playing cards by Virgil Solis. The larger cartouche shows Orpheus playing to the beasts, the smaller, oval cartouche is now too worn to be legible. Construction The organ case is of frame and panel construction in oak, with carved capitals and turned, applied roundel frames, all with oil painted decoration. The internal floor boards are modern softwood boards, running side to side. Schott, Baines and Yorke suggest the likely arrangement of the organ, with five ranks of pipes controlled by 10 stop knobs. Only part of the workings survive: two bellows, a single pipe and several fragments. For an analysis of the instrument, see Schott, Baines and Yorke (1998), and Rose (2002). The construction of the harpsichord ‘is of a very high order’ but ‘a few details suggest that making a harpsichord was a much less familiar process than, presumably, making virginals.’(Rose, 2002, p.301) Theewes designed the harpsichord with a ‘heavy, shallow and percussive action’. Modifications Extensive losses to the keyboard, soundboard, painting and leather as a result of water damage, and without the workings of the organ. These losses presumably occurred before 1839 when a published description records it as already a wreck. In 1874 the South Kensington Museum, as it was then, borrowed the instrument for the 1874 Exhibition, at which point some repair work may have been carried out. After it was given to the Museum in 1890, various repairs and replacements were carried out before it was put on display, apparently including the rebuilding of the back, the two hinged panels (painted blue) of the harpsichord lid which are scarfed to the surviving fragment bearing the Theewes signature. Numerous areas of repainting and overpainting, with large areas of discoloured varnish (See also Rose 2002 p.282) |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | Inscribed on inner surface of lockboard: 'Ludowicus Theews me fesit' |

| Gallery label |

|

| Credit line | Given by Mrs Luard-Selby, Igtham Mote, Kent |

| Object history | Given by Mrs Luard-Selby, Igtham Mote, Kent. Described on acquistion as " Organ-Harpsichord or Claviorganum. A combination of an organ & a harpsichord, permitting them to be played either separated or together, the latter being effected by means of a stop or a pedal and yielding a sustained sound. These instruments are in a most defective condition; the organ, however, seems to have contained fire stops (wood & metal), probably Open Diapason, Stopped Diapason, Principal Twelfth and Fifteenth. Of the oaken pipes, only one, tenor C, now remains, and of the manual only one black Key. The wind, which was supplied by two single-acting bellows, was, in the case of at least one stop, conveyed by paper tubes to a separate sound-board of curious construction. The pallets are like those in use at the present day. The harpsichord is made of oak, and has been decorated internally with colour and stucco ornament and externally with leather, stamped & gilt. The inside of the lid is painted; among the details is a medallion with the subject of Orpheus charming the beasts. The case of the organ also is oak, constructed in panels separated by pilasters, painted & gilt, the decoration consisting of strapwork, and of medallions containing the armorial shields and two crests. The name of the maker is painted on a panel which originally stood behind the key-board, and reads "LODOWICVS.THEEWES.ME.FESIT.1579", which is probably a Latinized form of the English surname Thew (Theewe?). These instruments [referring to 125 and 126-1890] originally stood in the Chapel of Igtham Mote, near Sevenoaks, Kent. Probably English. The claviorgan includes the only signed and dated harpsichord of the 16th century to have survived, from the whole of northern Europe. The quality of craftsmanship is high. In the 19th century the harpsichord suffered much water damage and lost some original parts. It is no longer playable but copies of both sections have been built (separately). The working parts of the organ are lost or fragmentary, but the case survives almost complete, though with the back apparently rebuilt. It has been suggested that the back must originally have been open to allow the sound to get out but a modern copy of the organ (Goetze and Gwynn) shows that was not necessary, provided the instrument had been tuned with the case configured as it would be for playing. Commentary, taken from Rose 2002 pp.299 The organ never had its own keyboard, and must therefore have been intended to be played from another instrument. It is not possible to point to any conclusive evidence that the harpsichord was adapted to fit the organ, while it is clear that the organ case was built to suit the harpsichord. It may never be possible to say whether the whole instrument was conceived at once or whether the combination was an afterthought, but the decorative styles are very close in date. However it seems strange that the harpsichord case leather covering continues along the spine, while the undecorated back of the organ case (though rebuilt), which lacks the mouldings seen on the front and sides, suggests that it was meant to stand along a wall. Although there are not mouldings in common there is no strong reason to doubt that Theewes built the organ. The case does suggest that it came from an experienced architect or joiner rather than a harpsichord maker or organ builder (Rose 2002, p301). Ownership of the claviorgan Roper The earliest coat of arms on the claviorgan (discovered in 1947) is that of the Roper family. Rose (2004) argues that the most likely member of the family to have commissioned the instrument in 1579 is Anthony Roper (1544-97), son of William Roper and Margaret More (the daughter of Sir Thomas More), citing the close match between the arms on the organ case (which are much damaged) and those on his alabaster funeral monument in Farningham church, Kent, both bearing the crescent moon heraldically appropriate to a second son. (The painted rope pattern in the claviorgan key well may be a pun on the owner’s name, although similar ornament has been found on another virginals.) The two families, the Mores and the Ropers, were closely connected by friendship, by their professional activity as lawyers, and by their adherence to the Catholic faith through difficult times. As the younger of two sons, Anthony inherited the estate of Farningham Manor, Kent on the death of his father in 1577/78, and appears to have lived almost entirely there from 1578, with his family. (Restrictions on Catholics became ever more severe during Elizabeth’s reign and from 1593, recusants were not permitted to travel more than five miles from their place of abode. ) Although neither the claviorgan nor any other furniture is mentioned in his will, the claviorgan is likely therefore to have been kept at Farningham Manor (demolished in the 18th century), where a later inventory (1684) refers to the Organ Room (though there was no organ there by this time), suggesting that the traditional room name remained in use. Anthony Roper is known to have had close connections to Thomas Tallis (who, Rose argues ‘probably remained a Catholic at heart’), and very probably knew William Byrd (who ‘certainly was’), two of the leading musicians of the day. With Farningham within easy reach of London and the palaces of Greenwich and Eltham, where the Chapel Royal attended the monarch, (Farningham is about 12 miles from Greenwich), it seems highly plausible that both men visited Farningham, and played the claviorgan there. Rose also speculates ‘that Anthony Roper’s main purpose in buying the claviorgan was to accompany the Catholic Mass… at Farningham, and that the idea of combining the organ with a harpsichord, so that it was an all-round instrument for domestic music-making, was to make its primary purpose a bit less obvious.’ Hoby Painted over the Roper arms are those of Sir Edward Hoby (d.1617) and his wife Elizabeth Carey (daughter of Henry Carey, Baron Hunsdon who was Queen Elizabeth’s cousin), which are presumed to have been added some time between 1582 (when they married) and 1605 (when she died), but probably after the death of Anthony Roper in 1597. No mention of the claviorgan has been found in family papers. It might have been kept at the Hobys’ family house Bisham Abbey, on the Thames near Marlow, west of London. Hoby entertained Elizabeth I regularly at Bisham, and Charles I after the queen’s death in 1603. An alternative location is Queenborough Castle on the Isle of Sheppey (30 miles from Farningham). In 1597, the year of Anthony Roper’s death, Sir Edward Hoby was appointed constable of Queenborough Castle (demolished 1650) on the Isle of Sheppey, in an important strategic position overlooking the mouth of the River Medway and the Thames estuary. Both Sir Edward and his wife had strong family links with the Isle of Sheppey, and Hoby acquired two other houses in Sheppey during the 1590s. A description of the castle in 1629 records a ‘noble large dining room or hall, round the top of which were placed the arms of the nobility and gentry of Kent, and in the middle those of Queen Elizabeth.’ (Hasted’s History and topographical survey of the county of Kent (1798)). Selby (Ightham Mote) The claviorgan disappears from historical record until 1828 when it appears, at the east end of the chapel in one of the drawings made by William Twopenny of Ightham Mote, Kent, a manor house with the earliest parts dating from around 1320, and again in 1839 (Colbran’s new guide for Tunbridge Wells) also recorded in the chapel. The current chapel (occupying space probably designed in the 1520s as a linking long gallery) is not recorded as such before the early 19th century, when it was fitted out with bought-in, medieval and later furnishings. It seems possible that the Selby family, owners of Ightham Mote, bought the claviorgan in the 17th century, but perhaps more likely that it was purchased for use in the chapel in the early 19th century, and that various alterations to the instrument were carried out at that time in an attempt to get the instrument into working order. |

| Historical context | Lodewyk Theewes (c1540(?)- 1589(?)) (for a fuller account see Rose, 2004) Lodewyk Theewes is likely to have been born c1540. (His name was probably pronounced ‘tay-wiz’.) He came from Antwerp where he became a member of the Guild of St Luke in 1561, and was married in 1564. Both his father Jacob and his uncle Lodewijk also made keyboard instruments. Following the revolt of 1566-7, and mass exodus of Calvinists, Theewes and his wife and two children are recorded in London from 1567 or 1568, where he was a member of the Dutch church in Austin Friars, in the parish of St Martin-le-Grand, one of the London ‘liberties’ in which residents were beyond the reach of officers of the Crown, and thus had more freedom to establish their businesses and take apprentices. (In the Return of Aliens a large number of immigrants are registered in the parishes of St Martin’s le Grand and Blackfriars.) The Dutch church was a large, established Dutch-speaking community. Theewes served as a Deacon for 10 years, and from 1585 an elder, and was clearly an active and generous member of the church. In 1568 he was recorded as a ‘virginall maker, a Ducheman, and denizen’ living in the parish of St Martin-le-Grand, London. Letters of Denization record Thewes as receiving his denization on 2 April 1574. (Unlike Naturalization, Denization was not sufficient for inheriting lands, and did not confer any benefit on children born previously to the date of the Grant.) Rose cites contemporary documents to show that Theewes enjoyed the patronage of the court, but no other instruments by him have been traced. He also suggests that Theewes might well have been able to find every craftsman he needed to make the claviorgan within his own Dutch community: a bookbinder for the leather covering (and coffermakers to apply it to the case), a smith for the fine iron hinges and clasps, turners for the roundel frames, joiners to make the organ case, and painters and gilders to decorate it. Use of the claviorgan (See Charlston) The organ and harpsichord could be combined in several general ways. Firstly, both parts could be played at the same time. The three registers of the harpsichord can all be turned on and off, which means that the organ can be played from the single (harpsichord) keyboard without the harpsichord strings sounding at all. It was also possible to disengage the organ action from the harpsichord by means of a coupler. It must have been possible to play a harpsichord bass against an organ and harpsichord treble, and an organ and harpsichord bass against harpsichord alone in the treble. The organ was equipped with a tremulant and a toy stop, perhaps nightingale or other birdsong. The harpsichord may also have been fitted with brays to produce an arpichordum (causing the strings to rattle against brass fittings) or buff stop effect. The two bellows fitted in the bottom section of the case and each would have been operated with a cord running though a hole in the case, possibly through the back or the end. Historical context Claviorgans in 16th century England (see Charlston) The name claviorgan is anglicised version of claviorganum (harpsichord and organ combined). It uses the single keyboard of the harpsichord to control the action of the organ below it by means of stickers that project through slots cut in the underside of the harpsichord. Such instruments were the standard keyboard instrument in European court circles north of the Alps and were also known in Italy and Spain. They would have been played on a regular basis, in both solo and ensemble repertoire, with or without voices. Only three 16th-century claviorgans (or former parts of claviorgans) are known to have survived: the Rossi spinet, the Theews claviorgan and an undated example made between about 1550 and 1600 in the collections of the Kunsthistorisch Museum in Vienna. [See also FALLETTI, Franca; Meucci, Renato;, Rossi-Rognoni; eds: Marvels of sound and beauty. Italian baroque musical instruments, [Exhibition, Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia, 2007]. (Florence, Firenz Musei, Giunti Editore S.p.A., 2007), p.32: Claviorgan (1639) by Valentin Zeiβ, Salzburg, Salzburger Museum Carolino Augusteum.] No pieces of music have been found which specifically call for performance on a claviorgan, but all surviving Tudor and Elizabethan solo keyboard music can be played on it. The combination of plucked and sustained tone is a very logical one and clearly valued at the time. Those with the wealth to possess one (and a player in their service with the necessary technical understanding) would have had a seemingly unlimited resource of sounds and registration possibilities. With four split organ stops and three harpsichord registers, all independent of each other, the instrument offers about 4,000 different combinations of stops, without taking into account the provision of a tremulant, toy stop or the harpsichord brays. The claviorgan’s versatility in dynamic and tone meant that it could fulfil various musical functions, such as song, dance and liturgical. Henry VIII owned several claviorgans (catalogued by van Wilder in 1547), and it seems likely that they were used in solo music and ensemble performance. Such impressive instruments, opulently decorated would have been appropriate diplomatic gifts and Charlston raises the possibility that the 1586 gifts of the Russia Company to the Russian court (which included ‘..organes, virginals, musicions,…’) might even refer to a claviorgan. At court the claviorgan could have been used in either or both the Presence Chamber (public, where loud wind instruments were heard – shawm, sackbut, recorders, flute, violin or viol – for dance and ceremonial music) and the Privy Chamber where softer instruments belonged (lute, viol, keyboard, harp, singers), for songs, dances and consort repertory, and which was where professional musicians tended to perform. Reconstructing the sound of the claviorgan Replicas (or an adapted replica in the case of the organ) of the two constituent parts of the claviorgan have been made and recordings combined digitally. Organ made by Martin Goetze and Dominic Gwynn Ltd., Welbeck,UK, 2008 Single manual harpsichord after Ioannes Couchet, Antwerp, 1645 (Russell Collection, Edinburgh, Catalogue No HS3-IC1645.7) made by David Evans, Henley, 2005. David Munrow, Instruments of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. (London, 1980) notes: “The tuning problem of such instruments can be fairly intractable, and the simultaneous effect of two such different sounds is a delightful novelty which soon palls.” |

| Summary | Object Type A claviorgan was fitted with strings as well as organ pipes. This example has lost almost all of these, though the soundboard, case and harpsichord stops still survive. Hardly any historic claviorgans are extant, but they were fairly widespread during the 16th century and a number were owned by Henry VIII. People This claviorgan was made in London by Lodewyk Theewes. He was a native of Antwerp in Flanders (now Belgium) and settled in London in the parish of St Martin-le-Grand, becoming naturalised in 1567. Time Signed and dated 1579, this claviorgan is the earliest surviving keyboard instrument to be made in Britain. It is painted according to the fashions of the time. The case is decorated with marbling and strapwork, the lid with monkeys and Orpheus playing to the beasts, a popular classical theme. The monkeys are derived from engravings of about 1550 by the German printmaker Virgil Solis (1514-1562). Furniture of this date is was often brightly coloured, but little of this decoration has survived. Prized in the 16th century, the claviorgan was more of a curiosity by 1660, when Samuel Pepys called it 'but a bawble with a virginall joining to it'. Place Before the claviorgan entered the collections of the V&A in 1890, it had long stood in the chapel of Ightham Mote, Kent. The house has no known connections with the families whose coats of arms decorated the instrument. |

| Associated object | |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 125 to CC-1890 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | July 5, 2001 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest