Mirror

ca. 1680 (Made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Chinese 'Coromandel' lacquer became very popular in Britain in the late 1670s and early 1680s, when quantities of screens and panels were shipped to Europe via trading ports in Indonesia and India. Transporting screens and panels that packed flat made good commercial sense to maximise cargo space. Large screens of about 180 cm high were used intact in Britain, although some were used as wall-panelling or later cut up for use as veneers on furniture. However the small-scale decoration and the unusually small dimensions of the lacquer panels used on this mirror frame, each about 80 cm high and 15 cm wide, would have been unsuitable for a room screen. Similarities between the lacquer panels used on this mirror and on a group of other similar furniture suggest that sets of small panels were ordered from China specifically for use as veneers on furniture. When digitally reassembled, the lacquer used on this frame forms a set of perhaps eight or ten panels with an overall design of Chinese deities. The lacquer technique involved cutting recesses into the surface of a black lacquer panel and filling them with pigment to create a brightly coloured design.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Softwood, carved, and veneered with Chinese Coromanel lacquer. |

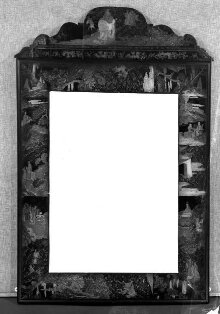

| Brief description | Mirror, of rectangular shape, with a convex frame veneered with sections of Chinese Coromandel lacquer, with a shaped cresting, the mirror frame made in England, about 1680. |

| Physical description | Summary description A rectangular mirror frame with a carved convex frame in the form of bolection moulding and an arched cresting, veneered with sections of Chinese lacquer. Structure The substructure of the frame is made of four lengths of softwood (probably pine) carved into a convex 'cushion' shape with a maximum depth of 5.7 cm, and mitred at the corners. The pieces are joined with tenons 3.5 cm wide, at the deepest part of the cushion. The frame is further reinforced by a subframe, 2 cm thick, also of softwood, which is lap-jointed at the corners and nailed to the back of the shaped parts. A moulded border 2 mm wide, of beech wood painted black, is nailed to the outer edge of the subframe to hide the raw edge of the lacquer. The cresting is formed of a shaped softwood board; two vertical oak tenons attached to the back slot into shallow blocks screwed to the back of the frame. No account has yet been discovered of the process for re-using Asian lacquer, but examination suggests that the lacquer was cut in sections from the original panels, and scraped back to leave a very shallow wooden substrate supporting the lacquer top layer. The sections of lacquer were then shaped to fit the cushion-moulded frame using heat and moisture, and glued on. The lacquer projects 8 mm within the inner edge of the frame to cover the edge of the glass mirror, and these projecting edges are reinforced by a supporting wooden fillet let into the inner edge of the frame. The mirror glass is held in place at the back by wooden blocks glued to the inner face of the pine frame. It is possible that the lacquer was ordered from China specifically for use as veneer. The sides of the mirror frame appear to have been made to fit the panels of lacquer, which are about 15 cm wide. The panels had to be be turned on their sides at the top and bottom of the frame, and some parts including the cresting are patched from smaller pieces. Originally the panels would have been lacquered and decorated on both sides of a wooden substrate. The lacquering technique involves the application, drying and polishing of two or three layers of lacquer, in this case stained with a black pigment. Under strong light the background has a brown and black streaky appearance. Once completely dry the lacquer is then carved with shallow reserves to create the design, leaving raised lines to show detail. A calcite base layer is applied in the hollows, followed by up to three layers of paint, and finished with a glaze. Uncut areas of lacquer are incised with narrow lines to add details suggesting waves, or pine-needles, some of which are coloured, but most are left without further decoration. The colours red, green and white were used with touches of gilding. The mirror glass is backed with a mercury-tin amalgam to create the reflective surface. Condition and repairs The lacquer has flaked off where it was cut through especially at the mitred corners. Flaking and areas where lacquer is missing have been filled and overpainted. The heating and bending process involved in shaping the lacquer to fit the contours of the frame probably affected the colours, requiring the colours to be refreshed. Decorative Scheme The four sides of the mirror frame are veneered with eight panels of lacquer, two on each side of the frame. The cresting is made up of eight small pieces fitted together. The scale of the decoration is smaller than that found on contemporary Chinese export screens. The lacquer was cut from a set of approximagely ten panels, which together made up a design about 80 cm high by 90 cm wide. Each each panel was about 15 cm wide. The two sides have pieces arranged vertically and were evidently chosen for their interest and boldness. The lower left and right sections of the sides appear to have been originally joined. The lacquer applied to the upper and lower edges of the frame had to be applied on their sides. By reassembling photographs of the pieces, the original scheme can be partially recreated. The decoration is a mix of Buddhist and Daoist symbolic figures of bodhisattvas (enlightened beings), some riding on animals, in a mountainous landscape, suggesting a meditative search, or on ocean waves, referring to Daoist stories of an ocean journey to an island of immortality, or immortals on their wave platforms. In the cresting is a white elephant representing wisdom, and a dragon. Along the bottom of the frame is a man with a wand riding a tiger, and a monk with a begging bowl; on the left a donkey, water buffalo and a figure with a fish; on the right side a deer representing longevity, and lion (kingship) and people making offerings. Colleagues in the Asian department advise that the scene was evidently designed for export to Europe. The original lacquer panels had upper and lower borders comprising a running geometric pattern and an outer border of carved bats and scrolls. Both elements of the border have been used along the lower edge of the cresting. The borders are also used to good effect on the frame itself. At each corner, the lacquer panels are carefully cut so that the geometric borders, from either the top or bottom of the original panels, are in the right position to form right-angled motifs which give a sense of balance to the frame. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | PROVENANCE The mirror was bought from the 'Dealers in Works of Art' J.M. Botibol, of 20,26,28 & 30 Hanway Street, London W1 for £150.00. The Museum authorities occasionally purchased furniture from dealers when it was brought to their attention. J.M. Botibol also supplied a pair of chairs from Woodhall Park and an Axminster carpet in the 1930s (W.18&A-1931 & T.7-1937) and a gilt overmantel mirror in the 1940s (W.33-1947). A label on the back of the Coromandel mirror indicates that the mirror was sold at Christies on 10 July 1924, lot 124, from the Mulliner Collection. H.H. Mulliner, a successful businessman who took a major shareholding of the firm of Lenygon and Co., the London interior decorators, formed a collection of English furniture and published 'The Decorative Arts In England 1660-1780' in 1924. No provenance is known for this mirror before it entered the Mulliner collection. HISTORY In the 1680s mirrors of this form were usually made as part of a set, placed between the windows of a room, above a matching table with two candle stands either side. The more expensive were decorated with costly materials such as lacquer, silver or ivory. This mirror frame is one of a small group of furniture from about this date with very similar Chinese export lacquer applied as veneers. The group includes similar mirrors at Boughton House, Northamptonshire and Ham House, Surrey, both of which retain their matching tables and stands, and at Ham there is also a matching cabinet on stand. The importation of sets of lacquer panels appears in the East India Company records but their subsequent use is not usually recorded. This small group of furniture associated with the V&A mirror seems to be an example of imported lacquer used immediately on arrival in Britain as veneers for furniture. It is possible that this group of furniture might have been made by a single British cabinet maker. The maker is as yet unidentified, although Gerrit Jensen is a possibility since he appears in the records of both Ham House and Boughton House. It is probable that the lacquer used was ordered from China, through the English East India Company, in sets of small panels suitable for use as veneers. Each set comprised about ten panels. The panels were all narrow strips 15 to 16 cm wide by about 80 cm high, which when set side by side formed small-scale scenes, which were very different from the larger scale designs on full-size folding Chinese lacquer screens imported at a similar date. Possibly the width of these particularly narrow panels was specified by the cabinet maker to fit the width of a contemporary mirror frame, while the height of the panels was intended to be exactly right for use on a table-tops or the front and sides of a cabinet. The flaw in this arrangement was that for the wider surfaces of the tables and cabinet, the panels had to be butted up next to each other, with still-visible joins, and that for the mirror frames, more than one the panel had to be used end to end on the sides to achieve the desired height. The other flaw was that the panels had to be set on their sides for the upper and lower edges of the mirror frames. The way the panels were patched together to cover the mirror frames made the original design unreadable, but it was the lustrous finish of the lacquer that created the impact of the finished piece. A complete set of ten panels, was used to decorate the front and sides of the cabinet at Ham House, while the matching mirror and table each also used an eight or ten panel set. The panels seem to have been ordered in groups of perhaps three with similar scenes, so that furniture supplied as a group would have a similar theme. The lacquer on all the Ham House pieces depict hunting scenes, while the lacquer on the Boughton House mirror and table depicts lake-side pavilions and fishermen. The V&A mirror depicts the world of the immortals. The set of Coromandel lacquered furniture at Ham House establishes a date for this group of lacquer veneered furniture. It was first added as a hand-written addition to an inventory taken in 1679. The taste for Coromandel lacquer was at its height in Britain in the late 1670s and early 1680s when it was rare and expensive, but became more widely available as imports increased in the early 18th century. By 1688 Stalker and Parker, in their 'Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing', described Bantam [Coromandel] work as 'now almost obsolete, and out of fashion, out of use and neglected...I think no person is fond of it, or gives it house-room, except some who have made new cabinets out of old Skreens. And from that large old piece, but the help of a Joyner, make little ones, such as Stands or Tables, but never consider the situation of their figures; so that in these things so torn and hacked to joint a new fancie, you may observe the finest hodgpodg and medly of Men and Trees turned topsie turvie...'. However Stalker and Parker were probably overly critical and exaggerated it's fall from fashion in order to promote the British japanning industry and sales of their book. TECHNIQUE The lacquer technique kuan cai (cut colour) involved incising designs into a lacquer surface and applying paint to the incisions, matt and gloss paint used to create variety and three-dimensionality, the gloss areas appearing more prominent. There are few historical Chinese sources on the method used, other than Xiu Shi Lu (The Lacquering Handbook) written by the 16th-century Chinese lacquerist Huang Cheng between 1567 and 1572. The lacquer base was first applied onto a wood or bamboo substrate, and once dry was incised. The background lacquer was often black, but could also be red or brown, using pigments which could both withstand the drying process and mask the natural brown colour of the lacquer. Huang Cheng describes two methods of painting the cut lacquer, the first a 'dry method' in which lacquer was brushed onto a recessed area, then powdered pigments applied on top, the second a 'wet method' in which pigments were mixed with oil and brushed onto the surface. Some pigments would not mix with lacquer, such as blue, white and pink, and would need the 'wet method'. Kuan cai objects are generally attributed to the Kangxi period (1622-1722). The technique was known in Britain as 'Bantam work' in late 17th century and 'Coromandel' in the 18th century, both terms deriving from the shipping routes from China. Bantam was a major trading city in Java, Indonesia, where the English established a trading post in the early 17th century. Chinese lacquer goods were later described as 'Coromandel' because they were shipped from China to Britain via the Coromandel Coast in south-eastern India. |

| Production | The mirror is very similar to one at Ham House, Surrey, part of a set (with table, two candlestands and a cabinet) that appears from inventories to have been introduced to the room above the chapel between 1679 and 1683 -- probably nearer to 1679 as it is listed in annotations to the inventory of that date, as well as in the 1683 inventory. See Peter Thornton and Maurice Tomlin, ‘The Furnishing and Decoration of Ham House’, Furniture History, Vol. 16 (1980), p. 114 and fig. 103. This suggests a likely date of our mirror as ca. 1680. |

| Summary | Chinese 'Coromandel' lacquer became very popular in Britain in the late 1670s and early 1680s, when quantities of screens and panels were shipped to Europe via trading ports in Indonesia and India. Transporting screens and panels that packed flat made good commercial sense to maximise cargo space. Large screens of about 180 cm high were used intact in Britain, although some were used as wall-panelling or later cut up for use as veneers on furniture. However the small-scale decoration and the unusually small dimensions of the lacquer panels used on this mirror frame, each about 80 cm high and 15 cm wide, would have been unsuitable for a room screen. Similarities between the lacquer panels used on this mirror and on a group of other similar furniture suggest that sets of small panels were ordered from China specifically for use as veneers on furniture. When digitally reassembled, the lacquer used on this frame forms a set of perhaps eight or ten panels with an overall design of Chinese deities. The lacquer technique involved cutting recesses into the surface of a black lacquer panel and filling them with pigment to create a brightly coloured design. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Other number | 2219/50 - RF number |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | W.39-1950 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | February 16, 2001 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest