Tombstone

circa 1305 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

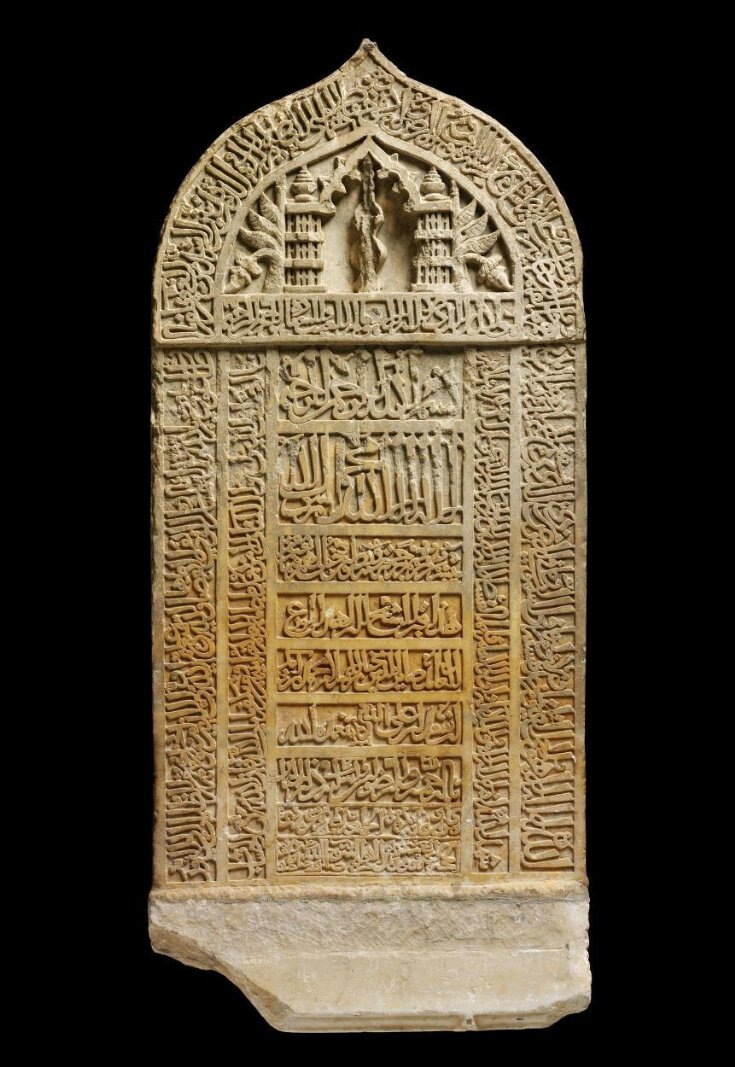

Tombstone of marble, carved in Khambhat, Gujarat, circa 1305, and shipped to Dhofar, now in Oman, where the date of death was added. The marble slab was carved as a stele with a tall, rectangular main section below a projecting upper section, which has the form of a pointed arch. A central panel within the upper section is carved in high relief and shows a lamp (now damaged) hanging within an arch, with half a plantain or banana plant filling the space on either side. The rest of the decoration consists of inscriptions in Arabic carved in low relief, including five quotations from the Qur’an.

The inscriptions

The motif of a lamp hanging within an arch is more or less conventional for Khambhat tombstones of this period, and the same can be said of the layout of the inscriptions, the styles of script employed, and the calligraphic compositions for standard phrases (see Lambourn, Carving and Communities, and compare V&A: A.12 and 13-1933). A stack of nine horizontal bands of different heights fills the centre of the main section. It contains the basmalah (“In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate”; line 1), the shahādah (“There is no god but God. Muhammad is the messenger of God”; line 2), a quotation from surah al-Tawbah (IX, 21; line 3) and the two-part epitaph (lines 4-7 and 8-9). A much longer quotation from the surah al-Baqarah (II, 255-7, to يخرجهم من الظلمات الى نوره) fills the outer framing band, which runs up the right side of the tombstone, around the upper section and down the left side. Within it are two vertical bands containing quotations from the surah Āl ‘Imrān (III, 18-19, to إنّ الدين عند الله الإسلام, and 26-7). The fifth quotation, from al-Ḥashr (LIX, 22), fills the horizontal band at the base of the upper section.

The styles of script

The main style of script is closely related to the chancery hands used in royal decrees and other official documents (compare Sheila S. Blair, Islamic Calligraphy, Edinburgh, 2006, fig. 9.7). This is evident from the letter forms -- e.g. the base of the letter alif (independent form) has an extension to the left, and the letter hā’ (final form) is written as a flourish rather than as a closed shape -- but even more so from the use of the “hanging” (ta‘līq) arrangement of the text, in which groups of letters run diagonally, from top right to bottom left, within the space allocated to the line of text. This practice is particularly noticeable in the quotation from al-Tawbah, where the scribe packed the groups of letters close together in slanting rows to fit them all in.

A second style of script was used for the basmalah and shahādah inscriptions, which reflect standardized compositions. The letter forms are very similar to those in the other inscriptions, with the addition of serifs to vertical strokes in many cases, but there is no ta‘līq stacking, as the scribe followed the horizontal base line in composing the text. The scale is larger, too: the band containing the shahādah is twice as tall as line 1, which is already taller than the rest. As a result, the vertical elements in the shahādah are comparatively long, which is especially evident in the composition of the first phrase, “There is no god but God” (to the right in line 2). Emphasizing part of the text by creating a forest of parallel vertical strokes, commonly used in inscriptions from Khambhat, is reminiscent of the ṭughrā element in royal decrees, which contains the name and title of the sultan (again compare Blair, fig. 9.7).

The epitaph

Lines 4-7 in the central stack contain the first part of the epitaph, which was executed in Khambhat in the main style of script. The text records the name of the deceased as “Shaykh … Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr ibn Sa‘d ibn ‘Ali”. The last word in the name, after “‘Ali”, was inserted or amended after the tombstone arrived in Dhofar, but it is not easily legible; it seems to be Shaykh Muhammad’s nisbah, an epithet often based on a person’s place of origin. The second part of the epitaph (lines 8-9) was also added in Dhofar, and in the same style of script as the nisbah, with letter forms extended by leaf-based decorative flourishes (foliation). This text places the date of Shaykh Muhammad’s death in “the year 4 after 600” in the Muslim calendar, equivalent to AD 1208 (but see below).

The inscriptions

The motif of a lamp hanging within an arch is more or less conventional for Khambhat tombstones of this period, and the same can be said of the layout of the inscriptions, the styles of script employed, and the calligraphic compositions for standard phrases (see Lambourn, Carving and Communities, and compare V&A: A.12 and 13-1933). A stack of nine horizontal bands of different heights fills the centre of the main section. It contains the basmalah (“In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate”; line 1), the shahādah (“There is no god but God. Muhammad is the messenger of God”; line 2), a quotation from surah al-Tawbah (IX, 21; line 3) and the two-part epitaph (lines 4-7 and 8-9). A much longer quotation from the surah al-Baqarah (II, 255-7, to يخرجهم من الظلمات الى نوره) fills the outer framing band, which runs up the right side of the tombstone, around the upper section and down the left side. Within it are two vertical bands containing quotations from the surah Āl ‘Imrān (III, 18-19, to إنّ الدين عند الله الإسلام, and 26-7). The fifth quotation, from al-Ḥashr (LIX, 22), fills the horizontal band at the base of the upper section.

The styles of script

The main style of script is closely related to the chancery hands used in royal decrees and other official documents (compare Sheila S. Blair, Islamic Calligraphy, Edinburgh, 2006, fig. 9.7). This is evident from the letter forms -- e.g. the base of the letter alif (independent form) has an extension to the left, and the letter hā’ (final form) is written as a flourish rather than as a closed shape -- but even more so from the use of the “hanging” (ta‘līq) arrangement of the text, in which groups of letters run diagonally, from top right to bottom left, within the space allocated to the line of text. This practice is particularly noticeable in the quotation from al-Tawbah, where the scribe packed the groups of letters close together in slanting rows to fit them all in.

A second style of script was used for the basmalah and shahādah inscriptions, which reflect standardized compositions. The letter forms are very similar to those in the other inscriptions, with the addition of serifs to vertical strokes in many cases, but there is no ta‘līq stacking, as the scribe followed the horizontal base line in composing the text. The scale is larger, too: the band containing the shahādah is twice as tall as line 1, which is already taller than the rest. As a result, the vertical elements in the shahādah are comparatively long, which is especially evident in the composition of the first phrase, “There is no god but God” (to the right in line 2). Emphasizing part of the text by creating a forest of parallel vertical strokes, commonly used in inscriptions from Khambhat, is reminiscent of the ṭughrā element in royal decrees, which contains the name and title of the sultan (again compare Blair, fig. 9.7).

The epitaph

Lines 4-7 in the central stack contain the first part of the epitaph, which was executed in Khambhat in the main style of script. The text records the name of the deceased as “Shaykh … Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr ibn Sa‘d ibn ‘Ali”. The last word in the name, after “‘Ali”, was inserted or amended after the tombstone arrived in Dhofar, but it is not easily legible; it seems to be Shaykh Muhammad’s nisbah, an epithet often based on a person’s place of origin. The second part of the epitaph (lines 8-9) was also added in Dhofar, and in the same style of script as the nisbah, with letter forms extended by leaf-based decorative flourishes (foliation). This text places the date of Shaykh Muhammad’s death in “the year 4 after 600” in the Muslim calendar, equivalent to AD 1208 (but see below).

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Carved marble |

| Brief description | Tombstone of carved marble, Khambhat, Gujarat, probably circa 1305. |

| Physical description | Tombstone of marble, carved in Khambhat, Gujarat, circa 1305, and shipped to Dhofar, now in Oman, where the date of death was added. The marble slab was carved as a stele with a tall, rectangular main section below a projecting upper section, which has the form of a pointed arch. A central panel within the upper section is carved in high relief and shows a lamp (now damaged) hanging within an arch, with half a plantain or banana plant filling the space on either side. The rest of the decoration consists of inscriptions in Arabic carved in low relief, including five quotations from the Qur’an. The inscriptions The motif of a lamp hanging within an arch is more or less conventional for Khambhat tombstones of this period, and the same can be said of the layout of the inscriptions, the styles of script employed, and the calligraphic compositions for standard phrases (see Lambourn, Carving and Communities, and compare V&A: A.12 and 13-1933). A stack of nine horizontal bands of different heights fills the centre of the main section. It contains the basmalah (“In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate”; line 1), the shahādah (“There is no god but God. Muhammad is the messenger of God”; line 2), a quotation from surah al-Tawbah (IX, 21; line 3) and the two-part epitaph (lines 4-7 and 8-9). A much longer quotation from the surah al-Baqarah (II, 255-7, to يخرجهم من الظلمات الى نوره) fills the outer framing band, which runs up the right side of the tombstone, around the upper section and down the left side. Within it are two vertical bands containing quotations from the surah Āl ‘Imrān (III, 18-19, to إنّ الدين عند الله الإسلام, and 26-7). The fifth quotation, from al-Ḥashr (LIX, 22), fills the horizontal band at the base of the upper section. The styles of script The main style of script is closely related to the chancery hands used in royal decrees and other official documents (compare Sheila S. Blair, Islamic Calligraphy, Edinburgh, 2006, fig. 9.7). This is evident from the letter forms -- e.g. the base of the letter alif (independent form) has an extension to the left, and the letter hā’ (final form) is written as a flourish rather than as a closed shape -- but even more so from the use of the “hanging” (ta‘līq) arrangement of the text, in which groups of letters run diagonally, from top right to bottom left, within the space allocated to the line of text. This practice is particularly noticeable in the quotation from al-Tawbah, where the scribe packed the groups of letters close together in slanting rows to fit them all in. A second style of script was used for the basmalah and shahādah inscriptions, which reflect standardized compositions. The letter forms are very similar to those in the other inscriptions, with the addition of serifs to vertical strokes in many cases, but there is no ta‘līq stacking, as the scribe followed the horizontal base line in composing the text. The scale is larger, too: the band containing the shahādah is twice as tall as line 1, which is already taller than the rest. As a result, the vertical elements in the shahādah are comparatively long, which is especially evident in the composition of the first phrase, “There is no god but God” (to the right in line 2). Emphasizing part of the text by creating a forest of parallel vertical strokes, commonly used in inscriptions from Khambhat, is reminiscent of the ṭughrā element in royal decrees, which contains the name and title of the sultan (again compare Blair, fig. 9.7). The epitaph Lines 4-7 in the central stack contain the first part of the epitaph, which was executed in Khambhat in the main style of script. The text records the name of the deceased as “Shaykh … Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr ibn Sa‘d ibn ‘Ali”. The last word in the name, after “‘Ali”, was inserted or amended after the tombstone arrived in Dhofar, but it is not easily legible; it seems to be Shaykh Muhammad’s nisbah, an epithet often based on a person’s place of origin. The second part of the epitaph (lines 8-9) was also added in Dhofar, and in the same style of script as the nisbah, with letter forms extended by leaf-based decorative flourishes (foliation). This text places the date of Shaykh Muhammad’s death in “the year 4 after 600” in the Muslim calendar, equivalent to AD 1208 (but see below). |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | Epitaph, part one:

هذا قبر الشيخ الزاهد الورع / العابد صاين الدين مختار الاسلام محمد بن أبي بكر / ابن سعد ابن علي الد[...] تغمده الله / بالرحمة والرضوان وأسكنه في دار الجنات

Epitaph, part two:

وكان وفاته بكرة الجمعة اول يوم من شهر ذي / الحجة سنة اربع بعد ستمائة من الهجرة النبوية صلو[ة] الله على صاحبها و سلامه ((1) The word shown as "al-D[...]" in the first part of the epitaph, after the name 'Ali, is almost certainly a nisbah, or epithet, derived from a geographical location. It was added or amended after the tombstone reached Dhofar, by the same hand that added the second part of the epitaph. The word is difficult to read, and it has been interpreted variously as "al-Damrini" (Guest), "al-Damrani" (Porter), and "al-Damiri" (Lambourn).

(2) The year of Shaykh Muhammad's death is clearly written as سنة اربع بعد ستمائة, "the year 4 after 600". Nevertheless, the reading given by Guest (p. 409) is سنة اربع تعشر ("the year 14"), and he ignores the word ستمائة ("600") without explanation. Guest then translated this phrase as "714", which is clearly incorrect. On the face of it, the date of death is AH 604, which is equivalent to AD 1208. Tombstones of this type were not produced until the 1280s, however. It is true that other tombstones from Khambhat were commissioned posthumously, but in this case the tombstone seems to have been ordered from Gujarat during Shaykh Muhammad's lifetime, and the date of death added later, once Shaykh Muhammad was dead. The person who drafted this part of the epitaph may simply have made a mistake, but it is also possible that the writer intended the phrase "after 600" to mean "after the end of the seventh century (AH)". Either way, this would date Shaykh Muhammad's death to 1 Dhu'l-Hijjah 704, equivalent to 25 June 1305, a date that accords with the style of the tombstone.

)

|

| Object history | The tombstone is part of a production in Khambhat (Cambay) in Gujarat that supplied a market for Muslim grave-markers around the Indian Ocean, from East Africa to South East Asia, from the 1280s onwards (see Lambourn, Carving and Communities). In this case, most of the carving was certainly carried out in Khambhat, but the second part of the epitaph itself, containing the death date, was added in another hand after the death of the person commemorated. It is likely that this addition was made in the port city of Zafar (ظفار), now the archaeological site of al-Balid near Salalah in Dhofar province, Oman, where the tombstone was erected over the grave of Shaykh Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr ibn Sa'd ibn 'Ali in the early fourteenth century. The V&A acquired the tombstone from Lieutenant D. S. [Digby Scawen] Blunt of the Royal Air Force in 1932 for £25. Blunt had been on a posting to the Aden Protectorate and had returned to the UK by 1931, when he is recorded as serving in Plymouth. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | A.5-1932 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 25, 2009 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest