Lock

1680-1700 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This type of lock is a rim lock, with its mechanism entirely enclosed in a case to be mounted on a door. Unlike later mortise locks that were built into doors and might match the overall decorative scheme of a room, rim locks could be removed when the owner moved house, to be fixed to a door in the new house.

Locks and keys were symbols of ownership and authority. Lockplates and key escutcheons, made of highly reflective materials, provided the finishing touches to decorative schemes.

English locksmiths were based mainly in London and the Midlands and were renowned for their ingenuity. Wolverhampton produced, according to one writer in 1686, locks ‘curiously polisht and the keys so finely wrought, that ‘tis reasonable to think they were never exceeded’. The diarist John Evelyn recorded in 1654 that a lock with ‘rare contrivances’ could be viewed as a masterpiece, ‘esteem’d a curiositie even among foraine princes’.

Wilkes is perhaps the most famous of all the English locksmiths of this period because several of his ingenious detector locks have survived (see V&A Museum No. M.109-1926).

Locks and keys were symbols of ownership and authority. Lockplates and key escutcheons, made of highly reflective materials, provided the finishing touches to decorative schemes.

English locksmiths were based mainly in London and the Midlands and were renowned for their ingenuity. Wolverhampton produced, according to one writer in 1686, locks ‘curiously polisht and the keys so finely wrought, that ‘tis reasonable to think they were never exceeded’. The diarist John Evelyn recorded in 1654 that a lock with ‘rare contrivances’ could be viewed as a masterpiece, ‘esteem’d a curiositie even among foraine princes’.

Wilkes is perhaps the most famous of all the English locksmiths of this period because several of his ingenious detector locks have survived (see V&A Museum No. M.109-1926).

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Steel, brass, forged and chiselled, blued |

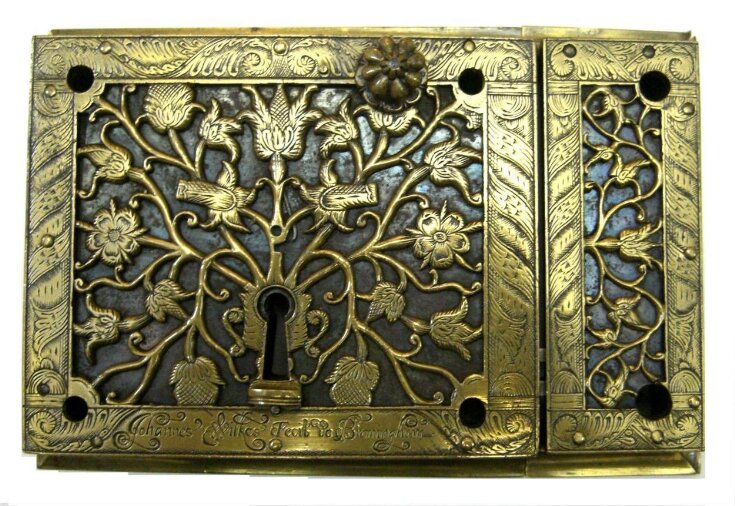

| Brief description | Rim lock of steel with pierced brass case, signed "Johannes Wilkes Fecit de Birmingham", England, Birmingham, ca. 1680 |

| Physical description | Door lock and hasp with steel mechanism and blued steel covering plate in rectangular pierced brass case, the border engraved with leaves and scrolls, the pierced ornament with twirling vines, sunflowers and tulips. The lower border is signed, "Johannes Wilkes Fecit de Birmingham". |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Marks and inscriptions | "Johannes Wilkes Fecit de Birmingham" (Lower border signed)

|

| Gallery label | DOOR LOCK

Steel and brass

England; second half of 17th century

207-1879

Steel formerly blued, the brass engraved and ground of design filled with black wax. The figurative keyhole cover is missing. Signed Johannes Wilkes fecit de Birmingham(07/1994) |

| Object history | This lock has open scrollwork in brass contrasting with a ‘blued’ steel base. This type of lock is a rim lock, with its mechanism entirely enclosed in a case to be mounted on a door. This lock has four bolts to control four levels of security. The mechanism of an identical lock in the Peter Phillips Collection was described by its owner as follows: "The master of the house could select, by turning the small knob at the top of the lock, the number of bolts (1 to 4) that he wished to put into operation. When set at number 4, which gives the maximum security, locking the top four bolts is achieved by just the turn of the key, but four turns of the key are required to withdraw these, ie. one at a time! There is however literally a "sting in the tail" with the top bolt, the one last withdrawn, for it triggers off the twin anti-burglar bottom bolts, and these can only be unlocked by a reverse action of the correct key." The Museum acquired this lock from the collection of John Charles Robinson. Robinson was appointed Curator of the Museum in 1853 at the age of 27. His appointment heralded a change in direction in the Museum's collecting activities. Robinson was a prolific collector and persuaded the Museum's first director, Sir Henry Cole, that historic works of art were as instructive to students as 'modern manufactures'. Under Robinson's guidance, some of the earliest purchases by the Museum included outstanding examples of European metalwork. The Musuem bought Robinson's own collection in 1879 for £6800. |

| Historical context | Locks and keys were symbols of ownership and authority. Lockplates and key escutcheons, made of highly reflective materials, provided the finishing touches to decorative schemes. Unlike later mortise locks that were built into doors and might match the overall decorative scheme of a room, rim locks could be removed when the owner moved house, to be fixed to a door in the new house. The bold proportions and twirling ornament are unmistakeably Baroque and would complement contemporary decoration in the house without necessarily matching exactly. On this example, even the inner workings are finely decorated. English locksmiths were based mainly in London and the Midlands and were renowned for their ingenuity. Wolverhampton produced, according to one writer in 1686, locks ‘curiously polisht and the keys so finely wrought, that ‘tis reasonable to think they were never exceeded’. The complicated mechanisms of locks made rooms secure while their intricate patterns in steel and brass turned their locks into works of art. The diarist John Evelyn recorded in 1654 that a lock with ‘rare contrivances’ could be viewed as a masterpiece, ‘esteem’d a curiositie even among foraine princes’. |

| Production | A lock with an identical pierced and engraved case signed 'John Webar Fecit" was in the Josiah Parkes Collection in Willenhall suggesting Wilkes may have used the same casemaker. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Association | |

| Summary | This type of lock is a rim lock, with its mechanism entirely enclosed in a case to be mounted on a door. Unlike later mortise locks that were built into doors and might match the overall decorative scheme of a room, rim locks could be removed when the owner moved house, to be fixed to a door in the new house. Locks and keys were symbols of ownership and authority. Lockplates and key escutcheons, made of highly reflective materials, provided the finishing touches to decorative schemes. English locksmiths were based mainly in London and the Midlands and were renowned for their ingenuity. Wolverhampton produced, according to one writer in 1686, locks ‘curiously polisht and the keys so finely wrought, that ‘tis reasonable to think they were never exceeded’. The diarist John Evelyn recorded in 1654 that a lock with ‘rare contrivances’ could be viewed as a masterpiece, ‘esteem’d a curiositie even among foraine princes’. Wilkes is perhaps the most famous of all the English locksmiths of this period because several of his ingenious detector locks have survived (see V&A Museum No. M.109-1926). |

| Associated objects | |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 207-1879 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 24, 2009 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest