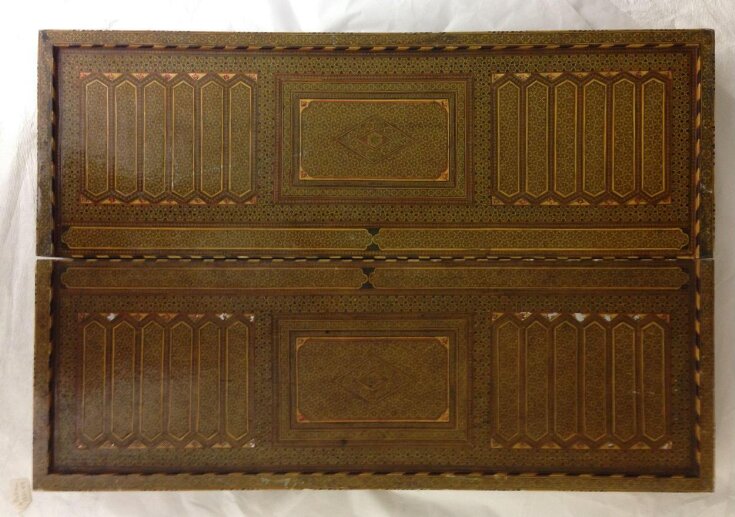

Backgammon Board

1850-1865 (made)

| Place of origin |

The following excerpt is taken from Javad Golmohammadi, “The Art of Iranian Decorative Veneer, Khatam-kari” in Art, Trade and Culture in the Islamic World and Beyond: From the Fatimids to the Mughals (London: Ginko Library, 2016), pp. 242-253:

Khatam is a polychrome decoration applied to wooden objects: it is a veneer and not an inlay but has the surface appearance of an inlay. The veneer created with the Khatam technique provides rich, delicate, and intricate decoration and as many as 400 pieces of multi-coloured materials may be fitted into a square inch to form geometric patterns by the juxtaposition of tiny triangular pieces. The raw materials for khatam comprise different kinds of wood, bone, and metal. Traditionally, the types of wood used are the redwood of the jujube tree (‘anab), light-coloured orangewood (chub-I naranj), dark rosewood (fufil), and for more valuable pieces, ebony (abnus), and medium brown teak wood (saf).

The earliest known example of a technique resembling khatam appears as juva-kari, a related method of decoration which uses wood alone. The earliest existing dated example of juva-kari work is found on the outer borders of a Quran stand, made by Hasan Sulaiman Isfahani and dated 760H./1360 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv.no. 10.218).

It is not exactly known when the art of khatam was first practiced in Iran. The Tadhikirat al-shu’ara mentions that Sultan Ahmad-I Jalayir (r. 1380-1410), ruler of Tabriz, was considered a master of several branches of art, such as painting and guiding, making bows and arrows, and khatam-bandi, indicating that the art of khatam-kari may go back to the fourteenth century. However, the oldest extant pieces date from the Safavid period (1501-1722) and during this time it seems that the art of khatam carried considerable prestige and was taught in royal circles. The art of khatam was so popular that there was a special bazaar devoted to it in Isfahan, and to this day it remains a craft associated with that city.

During the political turmoil at the end of the Safavid period, the production of all luxury crafts including khatam declined, but it was later revived in Shiraz under the patronage of Karim Khan Zand (r. 1750-1779). Khatam continued to be produced in the Qajar period. Under the patronage of the Qajar rulers, especially Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896), as well as other members of the court and the elite, the centre of the art of khatam was revived as craftsmen moved from Shiraz to Tehran to establish a new centre of production in the capital.

Khatam is a polychrome decoration applied to wooden objects: it is a veneer and not an inlay but has the surface appearance of an inlay. The veneer created with the Khatam technique provides rich, delicate, and intricate decoration and as many as 400 pieces of multi-coloured materials may be fitted into a square inch to form geometric patterns by the juxtaposition of tiny triangular pieces. The raw materials for khatam comprise different kinds of wood, bone, and metal. Traditionally, the types of wood used are the redwood of the jujube tree (‘anab), light-coloured orangewood (chub-I naranj), dark rosewood (fufil), and for more valuable pieces, ebony (abnus), and medium brown teak wood (saf).

The earliest known example of a technique resembling khatam appears as juva-kari, a related method of decoration which uses wood alone. The earliest existing dated example of juva-kari work is found on the outer borders of a Quran stand, made by Hasan Sulaiman Isfahani and dated 760H./1360 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv.no. 10.218).

It is not exactly known when the art of khatam was first practiced in Iran. The Tadhikirat al-shu’ara mentions that Sultan Ahmad-I Jalayir (r. 1380-1410), ruler of Tabriz, was considered a master of several branches of art, such as painting and guiding, making bows and arrows, and khatam-bandi, indicating that the art of khatam-kari may go back to the fourteenth century. However, the oldest extant pieces date from the Safavid period (1501-1722) and during this time it seems that the art of khatam carried considerable prestige and was taught in royal circles. The art of khatam was so popular that there was a special bazaar devoted to it in Isfahan, and to this day it remains a craft associated with that city.

During the political turmoil at the end of the Safavid period, the production of all luxury crafts including khatam declined, but it was later revived in Shiraz under the patronage of Karim Khan Zand (r. 1750-1779). Khatam continued to be produced in the Qajar period. Under the patronage of the Qajar rulers, especially Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896), as well as other members of the court and the elite, the centre of the art of khatam was revived as craftsmen moved from Shiraz to Tehran to establish a new centre of production in the capital.

Object details

| Category | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 3 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Woods; bone; paint; metal |

| Brief description | Rectangular shaped folding backgammon board with khatem-kari decoration, Iran, Qajar period, 1850-65 |

| Physical description | Rectangular shaped backgammon board comprised of two parts that fold into one another in an oblong shaped box, hinged together with small metal clasps. The interior is painted entirely with red paint, and consists of two small compartments on either side. The outside of the board is decorated with khatemkari veneer. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | This backgammon board was exhibited at the Paris Exhibition of 1867, and later acquired by the South Kensington Museum (V&A), for £10 and 16 shillings. |

| Summary | The following excerpt is taken from Javad Golmohammadi, “The Art of Iranian Decorative Veneer, Khatam-kari” in Art, Trade and Culture in the Islamic World and Beyond: From the Fatimids to the Mughals (London: Ginko Library, 2016), pp. 242-253: Khatam is a polychrome decoration applied to wooden objects: it is a veneer and not an inlay but has the surface appearance of an inlay. The veneer created with the Khatam technique provides rich, delicate, and intricate decoration and as many as 400 pieces of multi-coloured materials may be fitted into a square inch to form geometric patterns by the juxtaposition of tiny triangular pieces. The raw materials for khatam comprise different kinds of wood, bone, and metal. Traditionally, the types of wood used are the redwood of the jujube tree (‘anab), light-coloured orangewood (chub-I naranj), dark rosewood (fufil), and for more valuable pieces, ebony (abnus), and medium brown teak wood (saf). The earliest known example of a technique resembling khatam appears as juva-kari, a related method of decoration which uses wood alone. The earliest existing dated example of juva-kari work is found on the outer borders of a Quran stand, made by Hasan Sulaiman Isfahani and dated 760H./1360 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv.no. 10.218). It is not exactly known when the art of khatam was first practiced in Iran. The Tadhikirat al-shu’ara mentions that Sultan Ahmad-I Jalayir (r. 1380-1410), ruler of Tabriz, was considered a master of several branches of art, such as painting and guiding, making bows and arrows, and khatam-bandi, indicating that the art of khatam-kari may go back to the fourteenth century. However, the oldest extant pieces date from the Safavid period (1501-1722) and during this time it seems that the art of khatam carried considerable prestige and was taught in royal circles. The art of khatam was so popular that there was a special bazaar devoted to it in Isfahan, and to this day it remains a craft associated with that city. During the political turmoil at the end of the Safavid period, the production of all luxury crafts including khatam declined, but it was later revived in Shiraz under the patronage of Karim Khan Zand (r. 1750-1779). Khatam continued to be produced in the Qajar period. Under the patronage of the Qajar rulers, especially Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896), as well as other members of the court and the elite, the centre of the art of khatam was revived as craftsmen moved from Shiraz to Tehran to establish a new centre of production in the capital. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 935:1-1869 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 24, 2009 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest