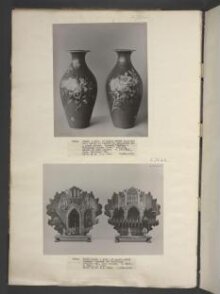

Pair of Letter Racks

1840-60 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Small domestic objects made of papier-mâché were very popular in the period 1840-1860. Manufacturers in the West Midlands, like Jennens & Bettridge whose name is painted and stamped on these letter racks, were highly inventive in their technical innovations. Their products made wholly or part of papier-mâché ranged from large pieces of furniture, like beds or settees, to trays, fans, card cases, crumb trays, and containers for stationery. Often skilled artists were employed to decorate pieces with a wide range of subjects, including landscapes, medieval buildings or naturalistic floral sprays. The slightly incongruous combination of outlandish flower or leaf shapes for the panels, and ecclesiastical themes, for the decoration, on these letter racks was typical of many papier-mâché pieces and reflected contemporary interest in the Gothic Revival as well as in botany.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Papier-mâché, japanned and painted; ebony |

| Brief description | Pair of letter racks in papier-mâché, painted and japanned, made by Jennens & Bettridge. English, 1840-60. |

| Physical description | Papier-mâché, japanned and painted, paper racks decorated in the Gothic taste with portions of a church seen in perspective. One shows a procession passing through a doorway with an organ case, and the other shows a sedilia and arches backed by a large window with banners. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Credit line | Given by Mr M. L. Horn |

| Object history | This pair of letter racks are examples of the popularity of small domestic objects made of papier-mâché.They are inscribed and stamped with the name of Jennens & Bettridge, one of the largest manufacturers of papier-mâché in the West Midlands. The firm, originally established in Birmingham by 1815, had premises in 3 Halkin Street West, London, from 1837. Although these letter racks are stamped London it is possible that they were actually made in the firm's Birmingham factory for sale in their London retail premises. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Small domestic objects made of papier-mâché were very popular in the period 1840-1860. Manufacturers in the West Midlands, like Jennens & Bettridge whose name is painted and stamped on these letter racks, were highly inventive in their technical innovations. Their products made wholly or part of papier-mâché ranged from large pieces of furniture, like beds or settees, to trays, fans, card cases, crumb trays, and containers for stationery. Often skilled artists were employed to decorate pieces with a wide range of subjects, including landscapes, medieval buildings or naturalistic floral sprays. The slightly incongruous combination of outlandish flower or leaf shapes for the panels, and ecclesiastical themes, for the decoration, on these letter racks was typical of many papier-mâché pieces and reflected contemporary interest in the Gothic Revival as well as in botany. |

| Bibliographic reference | The following excerpt is taken from Jones, Yvonne, Japanned Papier-Mâché and Tinware c. 1740-1940. Woodbridge, Antique Collectors' Club, 2012 (ISBN 978 1 85149 686 0), p.23-27:

‘Paper is believed to have been invented in China in the second century AD, and the Chinese art of making papier mâché objects is almost as ancient, but knowledge of paper-making spread only very slowly and it not reach Europe until the 12th century. Paper-mills were established in France in the late 15th century and soon after, French craftsmen began using paper pulp to make architectural ornaments, snuff boxes and other small articles. There were few paper mills in England until the late 17th century, so there was little pulp from which to make comparable articles, the paper imported from France being far too expensive to be pulped for the purpose.

By the 18th century, however, there were two quite distinct branches of paper mâché manufacture in England. One was allied to the making of paper hangings, and the other, to the japanning industry. Both branches took their lead from France and this, together with the name, has not only perpetuated the myth that papier mâché was French in origin, but also overshadowed its ancient eastern history.

Not only was the term papier mâché not recognised in 18th century French dictionaries, but the Journal de l’Agriculture du Commerce (1778) sourced it to England and to the first edition of Dossie’s book, The Handmaid to the Arts (1758). Its occurrence, much later in the French edition of the Paris Exhibition catalogue of 1855, may simply have been the result of the translation of texts supplied by English manufacturers. The term is, however, currently used in France today.

It has been suggested that the term derives from problems of communication between English employers and French émigré workers in the 17th century when papier mâché was probably taken to mean ‘mashed paper’ (or chewed paper)…. The crux was the cachet of a French sounding name and the penchant in some quarters if fashionable society in the late 18th century to look upon anything French as highly sophisticated.

…

Some of the advantages of papier mâché, gleaned from contemporary records, partly explain its attractions and may have been sufficient, at least until the mid-19th century, to outweigh what will be seen as its long and labour intensive production processes. Foremost was its suitability for japanning, which was much in vogue in the 18th century.

...

Furthermore, because it could be moulded into various forms, it required no joinery and was thus incredibly strong. As solid as wood, though less hard than most, it was said to blunt tools sooner, and although heavier in mass, its strength allowed it to be used in thin sections, rendering it perfect for small light objects….By the mid-19th century, it was found that it could be steam-moulded into any curve without fear of splitting. In short, it was considered superior to both wood and metal for being lighter, sounder, and admitting of a more beautiful finish’. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | W.94&A-1926 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | June 24, 2009 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest