Posset Pot

1630-1635 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Object Type

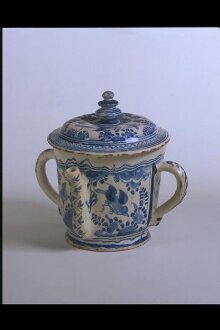

This represents one of the simplest forms of posset pot, a flaring two-handled beaker with a sucking spout and a lid to keep the contents warm. Other types were either cylindrical, or of the more popular and capacious baluster shape.

Ownership & Use

Many recipes for posset survive and there are numerous references to the drink in diaries and letters of the period. In 1625 Katherine Paston wrote to her son, a student at Cambridge: 'I hope thou dost not eat of those possety curdy drinks, which howsoever pleasing to the palate it may be for a time, yet I am persuaded are most unwholesome and very clogging to the stomach.' The diarist Samuel Pepys recorded drinking a posset after a night of revels in 1668. As well as being given to women after childbirth and to those returning from the fields in winter, they were used to revive anyone too weak to eat a full meal. Possets sometimes replaced the evening meal during Lent.

Design & Decoration

Posset pots were specially designed for this nourishing drink, which was sometimes thickened with bread, oatmeal or biscuits; the crust could be eaten with a spoon, while the liquid below could be sucked through the spout. A disproportionate number of posset pots have survived, as they were often used only on special occasions and given as gifts. Elaborate forms and designs evolved: for example, a series of delftware examples spanning the period 1631 to 1744 survive, as do several lead glass versions by the glassmaker George Ravenscoft (1632-81). At the end of the 17th century delftware, Staffordshire slipware and glass posset pots became large and highly decorated, indicating a high point in their ceremonial function which, by the middle of the 18th century, seems to have fallen into disuse.

This represents one of the simplest forms of posset pot, a flaring two-handled beaker with a sucking spout and a lid to keep the contents warm. Other types were either cylindrical, or of the more popular and capacious baluster shape.

Ownership & Use

Many recipes for posset survive and there are numerous references to the drink in diaries and letters of the period. In 1625 Katherine Paston wrote to her son, a student at Cambridge: 'I hope thou dost not eat of those possety curdy drinks, which howsoever pleasing to the palate it may be for a time, yet I am persuaded are most unwholesome and very clogging to the stomach.' The diarist Samuel Pepys recorded drinking a posset after a night of revels in 1668. As well as being given to women after childbirth and to those returning from the fields in winter, they were used to revive anyone too weak to eat a full meal. Possets sometimes replaced the evening meal during Lent.

Design & Decoration

Posset pots were specially designed for this nourishing drink, which was sometimes thickened with bread, oatmeal or biscuits; the crust could be eaten with a spoon, while the liquid below could be sucked through the spout. A disproportionate number of posset pots have survived, as they were often used only on special occasions and given as gifts. Elaborate forms and designs evolved: for example, a series of delftware examples spanning the period 1631 to 1744 survive, as do several lead glass versions by the glassmaker George Ravenscoft (1632-81). At the end of the 17th century delftware, Staffordshire slipware and glass posset pots became large and highly decorated, indicating a high point in their ceremonial function which, by the middle of the 18th century, seems to have fallen into disuse.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Tin-glazed earthenware, painted |

| Brief description | Posset pot with cover, tin-glazed earthenware, painted decoration of birds, rocks and flowers, London (Southwark, Montague Close, or Pickleherring), ca. 1630-1635. |

| Physical description | Posset pot with cover, tin-glazed earthenware, buff coloured body and a dull white, heavily crazed. The lid is whiter, uncrazed with pink patches, particularly on the underside. The base unglazed except for small patch of white glaze, slightly concave, without foot-rim. Geometric decoration, birds on rocks, flowers and insects in blue. The right handle and upper part of spout restored. Handles of oval section with sharp ridge on outside. (Alphabetic shape codes as used in appendix to Archer. Delftware. 1997) |

| Dimensions |

|

| Gallery label |

|

| Object history | Mr P. Hickey, Dublin. Purchased from Mr R.J. Charleston, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 1972. Made in London, at the Southwark, Montague Close or Pickleherring potteries |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Object Type This represents one of the simplest forms of posset pot, a flaring two-handled beaker with a sucking spout and a lid to keep the contents warm. Other types were either cylindrical, or of the more popular and capacious baluster shape. Ownership & Use Many recipes for posset survive and there are numerous references to the drink in diaries and letters of the period. In 1625 Katherine Paston wrote to her son, a student at Cambridge: 'I hope thou dost not eat of those possety curdy drinks, which howsoever pleasing to the palate it may be for a time, yet I am persuaded are most unwholesome and very clogging to the stomach.' The diarist Samuel Pepys recorded drinking a posset after a night of revels in 1668. As well as being given to women after childbirth and to those returning from the fields in winter, they were used to revive anyone too weak to eat a full meal. Possets sometimes replaced the evening meal during Lent. Design & Decoration Posset pots were specially designed for this nourishing drink, which was sometimes thickened with bread, oatmeal or biscuits; the crust could be eaten with a spoon, while the liquid below could be sucked through the spout. A disproportionate number of posset pots have survived, as they were often used only on special occasions and given as gifts. Elaborate forms and designs evolved: for example, a series of delftware examples spanning the period 1631 to 1744 survive, as do several lead glass versions by the glassmaker George Ravenscoft (1632-81). At the end of the 17th century delftware, Staffordshire slipware and glass posset pots became large and highly decorated, indicating a high point in their ceremonial function which, by the middle of the 18th century, seems to have fallen into disuse. |

| Bibliographic reference | Archer, Michael. Delftware: the tin-glazed earthenware of the British Isles. A catalogue of the collection in the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: HMSO, in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1997. ISBN 0 11 290499 8 |

| Other number | D9. - <u>Delftware</u> (1997) cat. no. |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | C.32&A-1972 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | January 29, 2000 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest