| Bibliographic references | - Lambert, Susan. Drawing, Technique & Purpose. London: Trefoil Books, ca. 1984. 141pp, illus. ISBN: 0862940478.

p. 59

- Calloway, Stephen. Aubrey Beardsley. London: V & A Publications, 1998. 224pp, illus. ISBN: 1851772197.

chapter 3

- Evans, Mark et al. Vikutoria & Arubāto Bijutsukan-zō : eikoku romanshugi kaigaten = The Romantic tradition in British painting, 1800-1950 : masterpieces from the Victoria and Albert Museum. Japan : Brain Trust, 2002

- Linda Gertner Zatlin, Aubrey Beardsley : a catalogue raisonne. New Haven : Yale University Press, [2016] 2 volumes (xxxi, [1], 519, [1] pages; xi, [1], 547, [1] pages) : illustrations (some color) ; 31 cm. ISBN: 9780300111279

The entry is as follows:

424

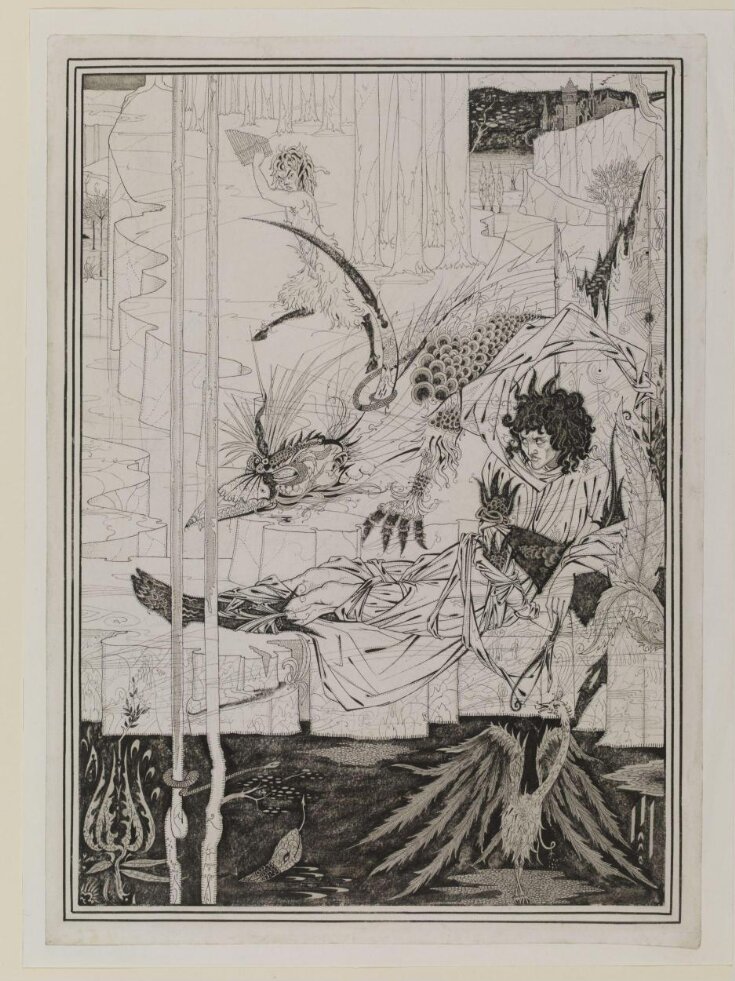

How King Arthur saw the Questing Beast, and thereof had Great Marvel

End of Book VIII

8 March 1893

Victoria and Albert Museum, London (E.289-1972)

Pen, brush, Indian ink and wash over pencil on white paper laid down on paper glued to base sheet; 15 3/4 x 10 11/16 inches (400 x 279 mm) through aperture to inner edge of mat; signed and dated.

INSCRIPTIONS: Recto inscribed by artist in black ink on base of left tree truck: A /u /b /r /e /y / B /ea /r /dsle /y / [on base of right tree trunk]: March / 8 / 1893 / [monogram at lower left on rock to right of tree]: AB / [at lower right]: [artist’s emblem]

FLOWERS: White poplar (time, courage) and cypress tree (death, mourning), clematis (mental beauty, artifice), stylised leaf.

PROVENANCE: J. M Dent; Dr. A. E. Tebb (by 1903); Baron Herbert von Garvens (Hanover), sold by 1946; Catherine Boelcke: Sotheby’s 17 April 1957 (58); bt. R. A. Harari, by descent to Michael Harari; bt. Victoria and Albert Museum in 1972 with the aid of a contribution from the National Art Collections Fund.

EXHIBITION: London 1894b (405);, 1966-8 (169); Tokyo 1983 (7); Munich 1984 (33); London 1993 (98); Montreal 1995 (11); London 1997-8 (90); Chiba, Japan 2002-3 (103); London 2003-4c (119); Sheffield 2004; Moscow 2014 (20).

LITERATURE: Sketch 26 September 1894 (p. 50); G.E.L. Artist October 1894 (p.361); Vallance 1897 (p.202), 1909 (no. 59.i); Gallatin 1945 (no. 284); Reade 1967 (p.315 n.56); Hodnett 1982 (p.222); Wilson 1983 (plate 3); Heyd 1986 (pp. 126-7, 147-8, 170); Fletcher 1987 (pp.39-40); Kooistra 1990 (pp.55-60); Samuels Lasner 1995 (no.22); Snodgrass 1995 (p. 251); Wilson in Wilson and Upstone 1997 (no. 90); Wilson in Wilson and Zatlin 1998 (p. 229 n.55)

REPRODUCED: Le Morte Darthur 1893-4 (following Book VIII in the parts issue; frontispiece for bound volume I where unnumbered p.2); Emporium 1895 (p.196); Reade 1967 (plate 56); Clark 1979 (plate 4); Wilson 1983 (plate 3).

In Book I, chapter xix, King Arthur commits adultery with King Lot’s wife, unaware that she is his sister. He impregnates her with Modred who, Merlin tells him, will destroy the kingdom. That night Arthur’s dreams leave him ‘sore adread’. To clear his head the next morning he goes hunting and then sits ‘in great thoughts’ near a fountain to which the ‘strangest beast’ comes to drink and goes away again (Book I, chapter XIX). Beardsley illustrates that moment but changes details of the story: he adds a sinister snake pointing a barbed tongue and a young Pan who runs disgustedly away as the beast slithers forward to drink from a murky body of water, not a fountain. The (suspicious) glances of the participants are full of ‘remarkable psychological realism’ (Wilson 1983, plate 3). The beast and Pan, at which Arthur stares, metaphorically forecast divisions in Arthur’s society that will be wrought by further violence and illicit sex.

The drawing was used as the frontispiece for Volume I of the bound parts. It is one of the few drawings Beardsley dated and signed with both his name and emblem, suggesting that it had ‘special significance’ for him (Wilson in Wilton and Upstone 1997, no. 90). One contemporary writer raves about it: reviewing J.M. Dent’s 1894 exhibition of over 600 black and white drawings that he had published, the reviewer for the Artist praises it as ‘one of the best if not the very best drawing in the rooms. The … King’s face horror-struck and loathing the nameless shape of the beast. The perspective and distance are drawn… in a masterly manner… This, being the frontispiece to the book, we take it to be one of the earliest drawings and is certainly the beast’ (G.E.L. Artist October 1894, p.361).

Beardsley’s conception of the king and the forces surrounding him helps the reader-viewer understand the court. For Malory, Arthur’s world consists of a duality: ideals of courtly knights - married love, civil action, even-handed justice - vie with various passions - civil, political and sexual (Kooistra 1990, pp.57-8). Beardsley suggests that the court’s power is concentrated in King Arthur by making him the main focus of the drawing. But Beardsley subverts the ideal king of tradition by placing him in a semi-recumbent position, hyponotised ‘by the slant-eyed gaze of the dragon-like beast’ and without his sword - symbols of ‘overall ineffectual kingship (Kooistra 1990, pp.59-60; Wilson in Wilton and Upstone 1997, no. 90). Arthur’s deflated posture is mirrored in his knight’s positions in other full-page drawings (compare nos. 454R, 531, 549, 587 below). The supine knights wear scant clothing and no armour, underscoring their inability ‘to achieve any kind of ideal’ (Kooistra 1990, p.66). Around Arthur lie insatiable appetites, insinuated in the ‘marvellous sequined’ dragon-like serpent with its ‘splendid and comic’ expression that foreshadows all the other beasts that help to destroy the kingdom because of the knights’ ‘ungovernable passions’ (Hodnett 1982, p.222; Kooistra 1990, pp.62-63). Should Arthur stand, the forces of unlawful sexuality, represented by Pan, the snake and the beast, might carry him away. These figures eye the king with hope (the beast and the snake) or scorn (Pan), and Arthur’s baleful glance at Pan speaks of his inability fully to refute its claim on him. To complete this initial rendering undermining the popular myth of Arthur as his knights as heroic, noble and chivalrous, Beardsley’s scene presents the king lying close to dank and scummy water in the midst of blasted vegetation and frozen ground. Through this frontispiece, Beardsley warns about the murky social environment of the story and triumphantly strikes the tone of violence as well as sexual and internal divisions ( Wilson in Wilson and Zatlin 1998, p. 229 n.55; Kooistra 1990, pp.61-66).

Many critics also take a view of the drawing as autobiography, with Beardsley as the tubercular, wasted but erotic young king (for example, Heyd 1986, pp. 126-7, 147-8, 170; Snodgrass 1995, p. 251; Wilson in Wilton and Upstone 1997, no. 90). Beardsley’s features are Arthur’s and they express terror as he ‘hunches away from [the beast] in fear’ at the same time as a clawed foot reaches towards Arthur’s genitalia - a portrayal of the temptation of the forbidden in its attraction and repulsion (Heyd 1986, pp. 126-7). Another view is also possible. In this drawing, the largest of his known pen and ink drawings, Beardsley brings his very personal ‘hairy style’, otherwise unused in this text, to a glorious culmination. Possibly its importance caused Beardsley to think about his method and content and he worked on it from autumn 1892 until he completed the drawings for the first part, published in June 1893. Unlike his usual practice, he both signed and dated the work. Plausibly he planned it as the frontispiece, for it contains the major point stressed in the first half of the book: Arthur growing to lead the knights but being undermined, revealed through his recumbent position, by lust (Pan) and the irrational (the beast).

King Arthur is influenced by Rossetti and Burne-Jones, but the ‘stereotype is broken by the tension in his frowning upward gaze, his unnatural twisted locks of hair, the swirl of his hood above his head, and the darting spermatozoid wrinkles in his gown’ (Hodnett 1982, p.222). The questing beast owes its origin to the gilded dragons in the chandelier in the Music Room and at the top of the valances in the Banqueting Room and Music Room at the Royal Pavilion, Brighton, UK. The snakes owe their origin to the serpents at the sides of the fireplace painted on fine linen and the gilded serpents around the columns in what is now the North Drawing Room (see also no.246 above). The dead tree trunk (Arthur’s castration?) connects the beast and the king physically and psychologically, and the ragged bird and the scuttling Pan underline the unresolved tension of the drawing (Snodgrass 1995, p. 251; Fletcher 1987, pp.39-40).

The flourishes of overlaid detail - including a treble clef, a phallus, a spider web, the tiny lines mediating between black and white areas, the phallic artist’s emblem - evoke Beardsley’s ‘training’ by seventeenth-century calligraphers but also detract from the power ’ (Reade 1967, p.315 n.56; Fletcher 1987, pp.39-40). This drawing ‘marks the climax of one of his early styles, blending into a unique mix influences from Japan, the early Italian Renaissance, the English Pre-Raphaelites and Whistler (Wilson, 1983, plate 3).

It was spoofed in the Sketch (26 September 1894, p. 50). And Walter Crane made a version of the dragon into a full-page illustration for Spencer’s ‘Faerie Queen’: A Poem in Six Books with the Fragment ‘Mutabilitie’ (1897, vols I, III)

|