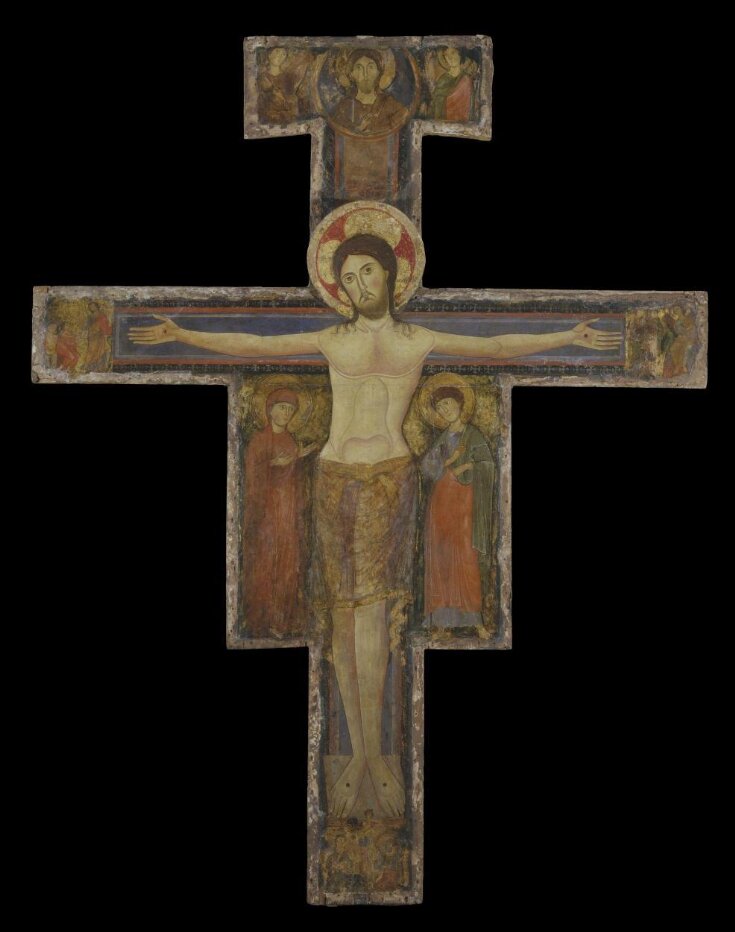

The Crucifixion with the Virgin Mary and St John

Oil Painting

late 12th century (painted)

late 12th century (painted)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Very little is known about the artist known as Alberto Sotio (active 1187). The church of SS Giovanni e Paolo in Spoleto contains frescoes by him and his circle and a crucifix, originally in the same church and now displayed in the Cathedral, is signed ‘Alberto So…’ and dated 1187. The V&A’s is very close in style and execution to the Spoleto work and is one the most important Italian paintings of this period in a British collection. Painted crucifixes such as these were intended as devotional pieces to be hung above the screen or an altar, or to be carried in procession, and act as aids to religious contemplation to anyone praying in the church or attending mass. Here, Christ hangs on the cross, confronting the beholder with open eyes. On His left is St. John the Evangelist and on His right the Virgin directs our gaze towards Him. At His hands and feet are three narrative scenes; on the left, the Harrowing of Hell, on the right Holy Women at the Sepulchre, and at the bottom the Denial of St. Peter. While Christ on the crucifix alludes to His human nature, the Triumphant Christ flanked by two angels at the top of the cross alludes to his divine nature and triumph over death.

This early crucifixion eschews a dramatic representation of the event, favouring a simple and direct approach as an aid to devotion. Later depictions of this scene (post 1250) tended to represent the dead Christ, with eyes closed and with the weight and suffering of his body suggested by the sagging of his corpse on the cross, and by the conspicuous grief of the Virgin and St. John at either side. Here the somewhat disconnected scenes and figures of the narratives serve as "clues" to the beholder who is supposed to meditate on the images before him as a means to understanding the immensity of Christ's sacrifice.

The panel is fairly well-preserved, although there are losses of paint on the Virgin's robe and the little scenes at the terminals of the cross. Few individual painters of this period are known by name, but this work, in addition to resembling that of Alberto Sotio in Spoleto, combines a number of central Italian motifs that suggest that it was painted in Umbria in the last quarter of the twelfth century.

This early crucifixion eschews a dramatic representation of the event, favouring a simple and direct approach as an aid to devotion. Later depictions of this scene (post 1250) tended to represent the dead Christ, with eyes closed and with the weight and suffering of his body suggested by the sagging of his corpse on the cross, and by the conspicuous grief of the Virgin and St. John at either side. Here the somewhat disconnected scenes and figures of the narratives serve as "clues" to the beholder who is supposed to meditate on the images before him as a means to understanding the immensity of Christ's sacrifice.

The panel is fairly well-preserved, although there are losses of paint on the Virgin's robe and the little scenes at the terminals of the cross. Few individual painters of this period are known by name, but this work, in addition to resembling that of Alberto Sotio in Spoleto, combines a number of central Italian motifs that suggest that it was painted in Umbria in the last quarter of the twelfth century.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | The Crucifixion with the Virgin Mary and St John (popular title) |

| Materials and techniques | tempera on canvas laid on panel |

| Brief description | Painted crucifix, showing Christ flanked by Mary and St John, with scenes of the Harrowing of Hell, the Holy Women at the Sepulchre, and the Denial of St Peter in the terminals, Circle of Alberto Sotio, late 12th century |

| Physical description | A painted crucifix depicting Christ flanked by Mary and St John. In the top terminal, a bust of Christ flanked by two angels. In the left terminal the Harrowing of Hell; in the right, the Holy Women at the Sepulchre; at the bottom, the Denial of St Peter. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Credit line | Given by Lord Carmichael of Skirling |

| Object history | Given by Lord Carmichael of Skirling, 1900. Extensive overpainting was removed in 1948, restoring the crucifix (in particular, the shape of Christ's loincloth) to a state closer to its original character. Historical significance: Very little is known about the artist known as Alberto Sotio (active 1187). The church of SS Giovanni e Paolo in Spoleto contains frescoes by him and his circle and a crucifix, originally in the same church and now displayed in the Cathedral, is signed ‘Alberto So…’ and dated 1187. The V&A’s is very close in style and execution to the Spoleto work and is one the most important Italian paintings of this period in a British collection. Few Italian paintings survive from 12th century. It has been estimated that over 90 percent of art from the era has been lost. Painted crosses are also rare, though it is assumed many Italian churches housed such crucifixes. There are 31 surviving crosses with the Cristus Triumphans datable to ca.1100-1230. Crucifixes such as these often include a variety of scenes from the Passion of Christ. Most include the scene of the Women at the Grave and the V&A crucifix appears to be the only surviving work to include this combination of scenes. While the painter of the V&A crucifix remains unknown, Lord Carmichael’s wife noted in his biography that the cross was believed to have been Tuscan, “associable with Berlinghiero Berlinghieri,” and dated to the early 13th century. (Carmichael, p.274). The crucifix has often been compared it to Alberto di Sotio’s 1187 painted cross from Spoleto while Van Marle believed the V&A crucifix to be the oldest painted cross in existence. Gnoli saw its linear style as evidence of Spoletan and Byzantine influence (Van Marle, p.201; Gnoli, pp. 15-16; Kaftal, p.880). Vavalà saw so many similarities with Umbrian, Sienese and Aretine crosses that she avoided giving a firm attribution, though was most in favour of a Sienese origin. She felt that it showed “strange combination” of the three regions. She identified the projecting moulding as Sienese, the face of Christ similar to the work of Alberto di Sotio’s assistant’s work in Assisi, and the body and the small figures in the terminals as Roman. She dated it to the later part of the 1100s. (Savalà, p.636-637). Garrison believed the V&A crucifix showed similarities to crosses from Lazio. However, he believed strongly that it was produced in Spoleto and “should be classified as Spoletan under strong Latian influence.” He felt that along with a tabernacle in Viterbo, the V&A crucifix provided a connection between the regional styles of Lazio and Umbria. In 1949 he refined his theory to place it as similar to Alberto di Sotio’s (or Sozio) painted cross yet with a Roman influence. He dated it to the late 12th or early 13th century (Garrison, 1949, p.187). Campini felt the V&A Crucifix was Spoletan from late 12th - early 13th century. He followed Garrison’s view that it was in the circle of Alberto di Sotio with Roman influence. (Campini, p.51). Kauffmann classified it as “Umbrian School, late 12th century” in his catalogue of paintings at the V&A. He noted that despite the presence of elements more commonly found in Tuscany (the “Harrowing of Hell” and the “Denial of St. Peter”), an origin in Arezzo – in Southern Tuscany and on the route to Perugia and Spoleto (both in Umbria) could explain the combination. Boskovits put the V&A crucifix in the same category as the Rosano crucifix, a crucifix from San Frediano in Pisa, the Montalcino cross, and a cross found in the Sienese Pinacoteca formerly in San Giovanni d’Asso because of the loose lines and flowing qualities. He believed the V&A cross to be by a Roman painter working in Rome in the early 1100s. (Boskovits, p. 19-20, 25). Andrea de'Marchi (in conversation) also suggested a Roman provenance due to the placement of the Virgin Mary's hands, which recalls (though in reverse) the position of the hands of the Madonna di S. Sisto, a 6th century icon venerated in Rome. |

| Historical context | A painted Crucifix is a painted wooden panel in the form of a cross, with a central figure of the crucified Christ. Other figures or scenes are sometimes also included on the apron (on either side of Christ’s lower body) and on the terminals (rectangular extensions of the cross arms); there may also be a roundel with a representation of God the Father or Christ Logos above the upper terminal. Painted Crucifixes were commonly either placed behind the altar or suspended from the chancel arch, as in Santa Croce, Florence. The double-sided construction of some painted Crucifixes suggests that they may also have been carried in liturgical processions. The iconography of the Crucifix was dominated by theological expressions of the incarnation and resurrection. In the 13th century the development of Franciscan theology, stressing Christ’s humanity, and the renewal of Byzantine artistic influences prompted not only the transition from a triumphant to a suffering Christ but also the changes in number and arrangement of secondary figures and scenes. Painted crosses became popular in Italy certainly by the 12th century, though the absence of surviving works makes more precise dating difficult. The earliest surviving Tuscan painted crucifix' represent Christ asChristus Triumphans, or the “Triumphant Christ” with his head up and eyes open. This form was supplanted in the 13th century with the Christus Patiens, or “Suffering Christ” type who is shown often with his head fallen on his shoulder and his eyes closed. The iconography of the suffering Christ appears to have developed out of a new interest in Christ’s human nature, the development of the feast of Corpus Christi and with increased importance given to the Eucharist. |

| Production | This work has been attributed alternately to the Tuscan and Umbrian Schools but is now generally accepted as Umbrian and appears very close to a work by Alberto Sotio of 1187 now in the Duomo of Spoleto, Umbria. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | Very little is known about the artist known as Alberto Sotio (active 1187). The church of SS Giovanni e Paolo in Spoleto contains frescoes by him and his circle and a crucifix, originally in the same church and now displayed in the Cathedral, is signed ‘Alberto So…’ and dated 1187. The V&A’s is very close in style and execution to the Spoleto work and is one the most important Italian paintings of this period in a British collection. Painted crucifixes such as these were intended as devotional pieces to be hung above the screen or an altar, or to be carried in procession, and act as aids to religious contemplation to anyone praying in the church or attending mass. Here, Christ hangs on the cross, confronting the beholder with open eyes. On His left is St. John the Evangelist and on His right the Virgin directs our gaze towards Him. At His hands and feet are three narrative scenes; on the left, the Harrowing of Hell, on the right Holy Women at the Sepulchre, and at the bottom the Denial of St. Peter. While Christ on the crucifix alludes to His human nature, the Triumphant Christ flanked by two angels at the top of the cross alludes to his divine nature and triumph over death. This early crucifixion eschews a dramatic representation of the event, favouring a simple and direct approach as an aid to devotion. Later depictions of this scene (post 1250) tended to represent the dead Christ, with eyes closed and with the weight and suffering of his body suggested by the sagging of his corpse on the cross, and by the conspicuous grief of the Virgin and St. John at either side. Here the somewhat disconnected scenes and figures of the narratives serve as "clues" to the beholder who is supposed to meditate on the images before him as a means to understanding the immensity of Christ's sacrifice. The panel is fairly well-preserved, although there are losses of paint on the Virgin's robe and the little scenes at the terminals of the cross. Few individual painters of this period are known by name, but this work, in addition to resembling that of Alberto Sotio in Spoleto, combines a number of central Italian motifs that suggest that it was painted in Umbria in the last quarter of the twelfth century. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 850-1900 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 15, 1999 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest