Cabinet on Stand

late 16th century-early 17th century (made)

| Place of origin |

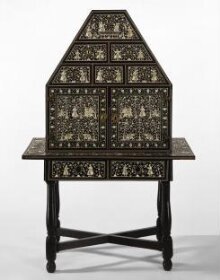

This cabinet on table-stand is a superb example of Indian furniture. The maker has decorated the exterior with rich ivory inlay. It shows pairs of courtly figures engaged in various activities. These include conversing while seated on a platform throne (takht), dancing, and hunting with falcons and on elephant back. The decoration is typical of a large group of furniture which scholars believe originated in the coastal regions of Gujarat and Sindh. This belief is based on a number of factors. Most importantly, documentary sources of the time confirm that this region was a centre of production for fine ivory-inlaid pieces specifically aimed at western markets. The style of the decoration is further evidence. For example, the figures have the pointed noses, wide eyes and curly moustaches found in Gujarati and Rajasthani paintings. The piece also has micromosaic decoration, a geometric inlay found over centuries in northern Italy and all over the Muslim world.

We can partly date the piece by the way the figures are dressed. The dancing figures on the second tier of drawers, for example, are wearing a distinctive type of robe with a pointed hemline (chakdar jama). This was fashionable at the Mughal court during the reigns of the emperor Akbar (1556-1605) and his successor Jahangir (1605-1627). The geometric patterns on the waist sashes (patka) were fashionable at Jahangir’s court. So too were the turbans worn by some of the male figures. The figures on the cabinet have fastened their jamas (robes) to one side of the chest, near the armpit. The emperor Akbar invited Muslims to tie their jamas to the right and Hindus to the left to make it easy to identify members of the different faiths. The figures here have jamas tied to the right and left. However, it is difficult to know whether this reflects religious distinctions or is simply more convenient in terms of design.

We can partly date the piece by the way the figures are dressed. The dancing figures on the second tier of drawers, for example, are wearing a distinctive type of robe with a pointed hemline (chakdar jama). This was fashionable at the Mughal court during the reigns of the emperor Akbar (1556-1605) and his successor Jahangir (1605-1627). The geometric patterns on the waist sashes (patka) were fashionable at Jahangir’s court. So too were the turbans worn by some of the male figures. The figures on the cabinet have fastened their jamas (robes) to one side of the chest, near the armpit. The emperor Akbar invited Muslims to tie their jamas to the right and Hindus to the left to make it easy to identify members of the different faiths. The figures here have jamas tied to the right and left. However, it is difficult to know whether this reflects religious distinctions or is simply more convenient in terms of design.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Parts | This object consists of 2 parts.

|

| Materials and techniques | Wood, veneered with ebony and inlaid with ivory and micromosaic; gilt copper mounts and brass carrying handles |

| Brief description | Cabinet on table stand, wood veneered with ebony, inlaid with ivory, Gujarat or Sindh, late 16th century or early 17th century, with later legs. |

| Physical description | Wood veneered with ebony, inlaid with ivory and micromosaic.This cabinet on table stand is a tour de force of Indian furniture-making. The exterior is richly inlaid in ivory, with pairs of courtly figures engaged in activities including conversing while seated on a platform throne (takht), dancing, falconry, and hunting on elephant back. The figures flank centrally positioned trees with spreading branches and split leaves. In contrast to the figures and profuse foliage of the exterior, the interior of the cabinet (below) is geometric in character; the drawer fronts and inner face of the doors are inset with a micromosaic inlay of stars and circles composed of transversely cut sections of woods and materials arranged in repeating patterns. The decoration of the piece is typical of a large group of furniture that scholars believe originated in western regions of the Indian subcontinent, specifically the coastal regions of Gujarat and Sindh. This attribution is based on a number of factors - principally the numerous contemporary documentary sources that confirm that this region was a centre of production for fine ivory-inlaid articles specifically aimed at Western markets. Supporting evidence is found in the character of the ornament. For example, the treatment of the figures, with their pointed noses and wide eyes, and the curly moustaches worn by men, conforms to Gujarati and Rajasthani painting traditions. Micromosaic decoration is found in northern Italy and all over the Islamic world, including Muslim Spain, Syria and Iran, and is also characteristic of western India, particularly Sindh, to which it was allegedly carried from Shiraz by Zoroastrian artisans. The handling of the ivory and the manner in which the figures are depicted suggest that this cabinet on table stand was made in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. The dancing figures on the second tier of drawers, for example, wear a distinctive type of robe with a pointed hemline (chakdar jama) fashionable at the Mughal court during the reigns of the emperor Akbar (reigned 1556-1605) and his successor Jahangir (reigned 1605-27). The sashes (patka) tied around the waists of the figures are decorated with geometric patterns resembling those in fashion at Jahangir's court, and some of the male figures wear turbans of a variety also popular in that period. As may be seen from the figures on the cabinet, jamas are fastened to one side of the chest, near the armpit. Under the direction of Akbar, Muslims were invited to tie their jamas to the right and Hindus to the left, making it easy to identify members of the different faiths. Figures depicted on this cabinet are shown with jamas tied to the right and left, although it is difficult to know whether this was in accordance with religious distinctions or simply more convenient in terms of design. The border around the table top is inlaid with scenes of men hunting (shikar) tigers and gazelles. Hunting themes permeate Mughal design and may be seen not only in painting, but also adorning a range of articles including carpets, clothing and metalwork. The presence of hunting scenes on this and many related cabinets has traditionally been viewed as a Mughal influence. However, such themes were equally in vogue on high-quality European cabinets of the period which were increasingly given to narrative decoration. These were executed in a variety of techniques, from inlaying materials into wood to etching on ivory, the latter permitting a fluidity of design that made it possible to replicate images directly from printed works, such as Gaston Phebus's Livre de la chasse (1563). Hunting motifs are also in evidence on contemporary textiles made in Bengal under Portuguese patronage, suggesting that this subject was a particular favourite among the Portuguese in the period. Although the basic form of the cabinet confirms that it was intended for European use, the unconventional trapezoidal upper section with drawers is atypical of Western furniture forms. Numerous cabinets with pyramidal tops were certainly made under Portuguese patronage in India. Related examples may be seen in the David Collection, Copenhagen, and in a private Portuguese collection. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Credit line | Given by Mrs Beachcroft |

| Object history | Presented to the British Museum by Mrs Beachcroft in 1831. Given by the British Museum to the V&A in 1931. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | This cabinet on table-stand is a superb example of Indian furniture. The maker has decorated the exterior with rich ivory inlay. It shows pairs of courtly figures engaged in various activities. These include conversing while seated on a platform throne (takht), dancing, and hunting with falcons and on elephant back. The decoration is typical of a large group of furniture which scholars believe originated in the coastal regions of Gujarat and Sindh. This belief is based on a number of factors. Most importantly, documentary sources of the time confirm that this region was a centre of production for fine ivory-inlaid pieces specifically aimed at western markets. The style of the decoration is further evidence. For example, the figures have the pointed noses, wide eyes and curly moustaches found in Gujarati and Rajasthani paintings. The piece also has micromosaic decoration, a geometric inlay found over centuries in northern Italy and all over the Muslim world. We can partly date the piece by the way the figures are dressed. The dancing figures on the second tier of drawers, for example, are wearing a distinctive type of robe with a pointed hemline (chakdar jama). This was fashionable at the Mughal court during the reigns of the emperor Akbar (1556-1605) and his successor Jahangir (1605-1627). The geometric patterns on the waist sashes (patka) were fashionable at Jahangir’s court. So too were the turbans worn by some of the male figures. The figures on the cabinet have fastened their jamas (robes) to one side of the chest, near the armpit. The emperor Akbar invited Muslims to tie their jamas to the right and Hindus to the left to make it easy to identify members of the different faiths. The figures here have jamas tied to the right and left. However, it is difficult to know whether this reflects religious distinctions or is simply more convenient in terms of design. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | IM.16&A-1931 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 15, 1999 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest