Panel

1560-1570 (embroidered)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

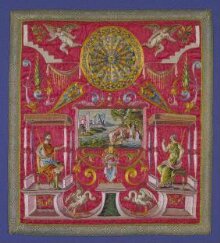

This is one of a set of panels that originally probably formed part of the decoration of a bed valance. A valance was a kind of pelmet round the top or base of a bed (the type of bed that had curtains that were drawn around it to keep out the cold).

A warrior and a woman are seated on either side of a rectangular framed subject. This probably shows the classical goddess Venus with her son Cupid, mourning the death of Adonis, Venus’ lover. The motifs, which include a laughing mask, birds, a vase and draperies, are in the grotesque style.

The term grotesque refers to the location of the designs, the grottos, which inspired the style, rather than to the subjects themselves. The most important of these, discovered in 1493, were parts of the celebrated Domus Aurea, the Golden House of Nero (ruled AD 54–68), in Rome. Designs of masks, draperies, vases and other motifs were found painted on walls and ceilings.

Italian artists introduced the grotesque style into France. French engravers adopted it immediately and also disseminated it in printed books. During the period 1550 to 1575 the grotesque style of ornament became the height of fashion in France. It was natural that grotesques were initially used for wall and ceiling decoration. They were then quickly adopted for tapestry wall hangings, in France as well as in Italy and Flanders. In France they were also employed for bed hangings, but for these the preferred medium was embroidery, as in this example. French inventories of the 16th century record many embroidered beds.

It is possible that the valance panel may have been part of a set made for Queen Catherine de Médicis (1519–89), or for some other member of the French court, but there is no firm evidence to back this up. The embroideries are of a very fine quality, however, and in the 19th century they were bound as an album inscribed ‘RICAMI DEI MEDICI’ (‘embroideries of the Medici’).

A warrior and a woman are seated on either side of a rectangular framed subject. This probably shows the classical goddess Venus with her son Cupid, mourning the death of Adonis, Venus’ lover. The motifs, which include a laughing mask, birds, a vase and draperies, are in the grotesque style.

The term grotesque refers to the location of the designs, the grottos, which inspired the style, rather than to the subjects themselves. The most important of these, discovered in 1493, were parts of the celebrated Domus Aurea, the Golden House of Nero (ruled AD 54–68), in Rome. Designs of masks, draperies, vases and other motifs were found painted on walls and ceilings.

Italian artists introduced the grotesque style into France. French engravers adopted it immediately and also disseminated it in printed books. During the period 1550 to 1575 the grotesque style of ornament became the height of fashion in France. It was natural that grotesques were initially used for wall and ceiling decoration. They were then quickly adopted for tapestry wall hangings, in France as well as in Italy and Flanders. In France they were also employed for bed hangings, but for these the preferred medium was embroidery, as in this example. French inventories of the 16th century record many embroidered beds.

It is possible that the valance panel may have been part of a set made for Queen Catherine de Médicis (1519–89), or for some other member of the French court, but there is no firm evidence to back this up. The embroideries are of a very fine quality, however, and in the 19th century they were bound as an album inscribed ‘RICAMI DEI MEDICI’ (‘embroideries of the Medici’).

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Silk satin embroidered with silk threads, attached to linen |

| Brief description | Panel, section of a bed valance, embroidered in France, 1560-70 |

| Physical description | Embroidered panel from a valance in the Grotesque style. The only one of the four panels which is not mounted and which therefore reveals how the embroidery was executed through a layer of red satin attached to a layer of undyed linen. At the side stands a warrior and a woman, with a rectangular framed subject between, possibly that of Venus with cupid mourning the death of Adonis. At the bottom is a small framed compartment with a pair of swans. The surrounding ornament includes a laughing mask, belts, a vase, strings of beads, birds, a circular canopy and draperies. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Object history | In the 19th century (?) each embroidery gained an edging of gold braid, and was mounted on a separate card covered with cream satin. The satin-covered cards were bound as an album in a red velvet cover inscribed RICAMI DEI MEDICI (Italian for 'embroidery of the Medici'). They may have been made for Catherine of Medici (Queen of France) or some other member of the Medici family, although there is no definite internal evidence to support this supposition. This embroidery has now been removed from its 19th century backing and therefore bears witness to the original method of putting the embroidery together. Historical significance: This object is a good example of the grotesque style of decoration which was at its height in the sixteenth century. It is a fine example of secular embroidery which draws on classical sources rather than on religious imagery. The embroidery is of a high standard and the state of preservation is excellent. Indeed, the quality is so high that it is not impossible that the embroidery was for Catherine de Medici (b. Florence, 1519- d. Paris, 1589) or one of her family although there is no internal evidence in the object to confirm this suggestion. According to Donald King, it compares favourably with similar items in the Musée des Tissus in Lyons, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and Waddesdon Manor. The association with Catherine is based on sound circumstantial evidence of her environment and predilections. She was a prominent patron of the arts and an influential figure, both during her reign as Queen of France (1547-59) and as Queen Mother of France (1559-89). Having learnt needlework skills initially in the Convent of the Murate in Florence (a centre of excellence), she evidently often spent afternoons 'working in silks' and later in life she took an interest in encouraging the dissemination of such skills, for example, founding with her husband L'atelier de la Trinité in Paris in 1551. There poor children could learn all textile arts and become skilled craftspeople. She no doubt also passed on similar skills to her daughter-in-law, the future Mary Queen of Scots who was to find much solace in such work during her long years of captivity. (Margaret Swain. The Needlework of Mary Queen of Scots. Bedford: Ruth Bean Publishers, 1973, pp.30-36). Orphaned shortly after her birth, Catherine, one of the richest young women in Europe, had immediately become a pawn in the dynastic endeavours of her Italian papal relatives, finally marrying the future Henri II of France. Her education in Florence and Rome gave her a grounding in Greek, Latin and French and knowledge of mathematics, as well as in the womanly skills of needlework. She became renowned for her charm, wit, understanding of the arts, and love of fine dress and textiles, and was well able to communicate with her father-in-law, Francis I, a great lover of the Italian arts. The timing of the spread of grotesque ornament in print culture coincided with the betrothal (1531) and marriage (1533) of Catherine de Medici to the future Henri II of France, and to the span of their twenty-five year reign. With a familial legacy in the patronage of the arts from her prestigious banking forebears, Catherine was no doubt familiar with the important painted decoration of the loggias in the Belvedere in the Vatican in Rome before she arrived in France. These decorations produced between 1518 and 1520 under the supervision of Raphael, who was both artist and the papal conservator of Roman Antiquities, established the grotesque style as an important decorative system, a counterpoint to regular classical architecture. The style was disseminated throughout Europe via prints, some of the first being circulated from Rome in the 1530s. It is clear that such prints had impacted on France by 1550 when Jacques Androuet Ducerceau published a major set of ornaments in Orleans. (Leonie Frieda. Catherine de Medici. London: Phoenix, 2005; Michael Snodin and Maurice Howard. Ornament. A Social History Since 1450). London: V&A, 1996, pp.36ff; Donald King. 'A Set of Embroideries', in Objects for a Wunderkammer, Colnaghi exhibition catalogue, London, 1981, pp. 242-254) |

| Historical context | This panel would have been joined to several other panels in order to form a long strip or valance which would have been used round a bed head. The skilfulness of the needlework suggests professional embroiderers or supremely skilled domestic embroiderers (possibly aristocratic women trained in convents). The valance is likely to have belonged to a set of bed furnishings. The beds they adorned were simple and rectilinear in shape. Such beds would also have been typical of the mansions lived in or built by Catherine de Medici in Italy and France during her lifetime. Peter Thornton reproduces a sketch from the Medici wardrobe accounts, dating to between 1582 and 1593, showing the shape of tester for which such embroideries might have been intended (ill.139, p. 133). The bed is similar to four Milanese beds of circa 1540 (ill.154-7, p. 143). Note, too, Sodoma's representation of what Thornton describes as 'an architect-designed bed' in which a decorative (embroidered?) textile valance surrounds the bed below a highly elaborate wooden entablature (Sodoma, Alexander visitng Roxana, Farnesina, Rome, ca. 1511 (ill.148, p.139). (Peter Thornton. The Italian Renaissance Interior, 1400-1600. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1991, 'Beds, Canopies and Lettuccio pp. 111-167). It is quite likely that the embroidered imagery derived from pattern books of designs which were increasingly available from the early 16th century onwards, although the precise source has not yet been traced. Both amateur and professional embroiderers worked from such publications, adapting the motifs to suit their needs and taste. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Summary | This is one of a set of panels that originally probably formed part of the decoration of a bed valance. A valance was a kind of pelmet round the top or base of a bed (the type of bed that had curtains that were drawn around it to keep out the cold). A warrior and a woman are seated on either side of a rectangular framed subject. This probably shows the classical goddess Venus with her son Cupid, mourning the death of Adonis, Venus’ lover. The motifs, which include a laughing mask, birds, a vase and draperies, are in the grotesque style. The term grotesque refers to the location of the designs, the grottos, which inspired the style, rather than to the subjects themselves. The most important of these, discovered in 1493, were parts of the celebrated Domus Aurea, the Golden House of Nero (ruled AD 54–68), in Rome. Designs of masks, draperies, vases and other motifs were found painted on walls and ceilings. Italian artists introduced the grotesque style into France. French engravers adopted it immediately and also disseminated it in printed books. During the period 1550 to 1575 the grotesque style of ornament became the height of fashion in France. It was natural that grotesques were initially used for wall and ceiling decoration. They were then quickly adopted for tapestry wall hangings, in France as well as in Italy and Flanders. In France they were also employed for bed hangings, but for these the preferred medium was embroidery, as in this example. French inventories of the 16th century record many embroidered beds. It is possible that the valance panel may have been part of a set made for Queen Catherine de Médicis (1519–89), or for some other member of the French court, but there is no firm evidence to back this up. The embroideries are of a very fine quality, however, and in the 19th century they were bound as an album inscribed ‘RICAMI DEI MEDICI’ (‘embroideries of the Medici’). |

| Bibliographic reference | Takahiko Sano (ed.) The European Art of Textiles, Osaka : NKH Kinki Medi Plan, 1995

no.29 |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | T.219A-1981 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 15, 1999 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest