The Continence of Scipio

Oil Painting

ca. 1463 - 1465 (painted)

ca. 1463 - 1465 (painted)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

Apollonio di Giovanni (ca.1416-1465) was born in Florence where he trained as an illuminator in the circle of Bartolomeo di Fruosino (ca.1366-1441) and Battista di Biagio Sanguini (1393-1451). He became a member of the Arte dei Medici e degli Speziali in 1442 and of the Guild of St Luke in 1443. Marco del Buono (1402-1489) joined the Guild of St Luke in 1443. Together they run the most important workshop in fifteenth-century Florence from at least 1446. They produced decorated furniture panels (‘forzieri/cassoni’, wedding chests, ‘deschi da parto’, birth trays, ‘spalliere’, wainscotting) as well as illuminated manuscripts.

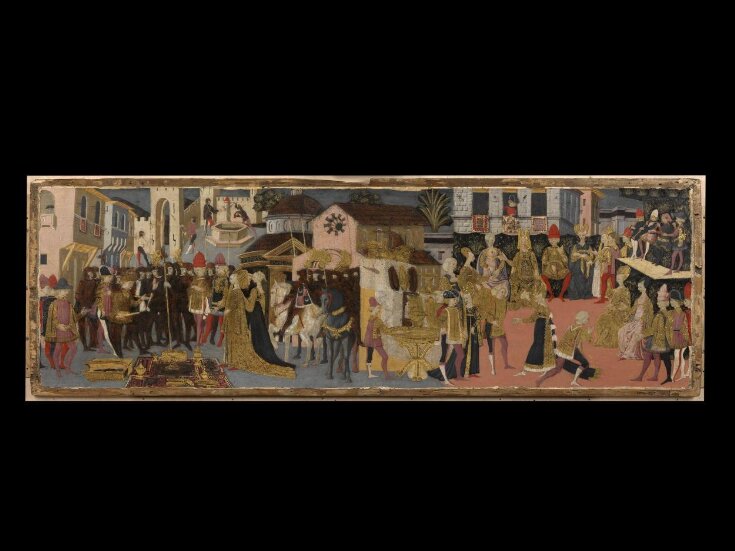

This panel is a detached part of a Florentine marriage chest, known as ‘cassone’, i.e. a wedding chest, made in the occasion of a marriage between two members of important families, and belonged to the bridal trousseau. These pieces had often appropriate scenes painted on them such as the here depicted ‘Continence of Scipio’. The Roman general Scipio Africanus, after the defeat of Carthage was offered a beautiful woman called Lucretia as his captive. But when he was told of her betrothal to the Carthaginian Allucius, Scipio nobly returned Lucretia to him and returned the gold sent as ransom by her parents. Scipio is shown standing by the carpet which is covered with gold objects sent as ransom, and on the other side the marriage takes place.

This panel is a detached part of a Florentine marriage chest, known as ‘cassone’, i.e. a wedding chest, made in the occasion of a marriage between two members of important families, and belonged to the bridal trousseau. These pieces had often appropriate scenes painted on them such as the here depicted ‘Continence of Scipio’. The Roman general Scipio Africanus, after the defeat of Carthage was offered a beautiful woman called Lucretia as his captive. But when he was told of her betrothal to the Carthaginian Allucius, Scipio nobly returned Lucretia to him and returned the gold sent as ransom by her parents. Scipio is shown standing by the carpet which is covered with gold objects sent as ransom, and on the other side the marriage takes place.

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Title | The Continence of Scipio (popular title) |

| Materials and techniques | tempera on poplar panel |

| Brief description | Cassone panel depicting the Continence of Scipio, workshop of Apollonio di Giovanni and Marco del Buono, ca. 1463-1465 |

| Physical description | On the left, a group of figures around a blanket covered with gold plates, in the middle a group of soldiers astride and a tall buffet, on the right, a group of figures dancing and musicians on a platform, architectural elements in the background surround the whole composition. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Style | |

| Object history | Bought in 1859 for £ 9,2 Historical significance: Originally attributed by Schiaparelli (1908) to a follower of Pesellino, and by Schubring (1915) to the Master of the Tournament of S. Croce, by Offner (1927) to the Dido Master and by Berenson (1932) to the studio of the Master of Jarves Cassoni, this cassone panel represents the Continence of Scipio, a popular subject at the time. Three similar cassone panels survive: one also attributed to the Workshop of Apollonio di Giovanni in the Art Institute of Chicago, another in collection of the Earl of Harewood, Leeds, and a third one, not by Apollonio, in the Courtauld Institute Galleries, London. This subject from Roman Republican history is mentioned by Plutarch, Livy, and other classical authors, as well as Petrarch and later writers. Cassoni were usually produced in pair and according to E. Callmann, the usual pendant to the Continence of Scipio would have been a scene of the Rape of the Sabines (two fragments and one panel of this subject attributed to Apollonio’s workshop survive: in the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh; the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; and the collection the Earl of Harewood, Leeds). The juxtaposition of these scenes may have been intended to contrast Scipio’s generosity in returning the captive Lucretia to her prospective husband with Romulus' unscrupulous attack on the Sabines, whom the Romans had previously invited to a banquet. The classical subjects are here portrayed in a contemporary Florentine idiom, reflecting thus the sought-after qualities that The Continence of Scipio and the Rape of the Sabines exemplify: on one hand the virtues of restraint and magnanimity , and, on the other, a decorous example of feminine submissiveness followed by a wife after her marriage. The composition is divided into two consecutive scenes: on the left is the representation of the continence of Scipio - identifiable by the inscription SCIPIONE on his hat, and his general’s baton - who stands in front of Lucretia and her promised husband on the other side of a blanket covered with presents. On the right, is depicted the celebration of Lucretia and Allucius’ wedding. These two scenes are separated in the middle by a group of soldiers, reminiscent of Paolo Uccello’s compositions, and a tall buffet known as a credenza, lavishly decorated with gold plates. These narrative divisions do not affect the fluidity of the composition, which seems superior to the above mentioned version of the Continence of Scipio in The Art Institute of Chicago (1933.1036). The identity of the patron who commissioned it is unknown, but his/her coat-of-arms is probably that portrayed on the surcoat of the man at arms on a white horse at centre/left of the scene. |

| Historical context | The term cassone stands in Italian for chest and relates to large and ornate pieces of furniture made in Italy from the 14th to the end of the 16th centuries. They were generally made on the occasion of a relatively important wedding and contained the bride's trousseau. Writing in the mid-sixteenth century, Vasari describes cassoni thus: ‘…citizens of those times used to have in their apartments great wooden chests in the form of a sarcophagus, with the covers shaped in various fashions…and besides the stories that were wrought on the front and on the ends, they used to have the arms, or rather, insignia, of their houses painted on the corners, and sometimes elsewhere. And the stories that were wrought on the front were for the most part fables taken from Ovid and from other poets, or rather stories related by the Greek and Latin historians, and likewise chases, jousts, tales of love, and other similar subjects…’. (Giorgio Vasari, translated Gaston du C. de Vere, Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, vol. 1, London 1996, p.267) These lavishly decorated cassoni, often combined with pastiglia decoration, were generally commissioned in pairs. Florence was at that time the main centre of production. The painted decorations usually represented episodes from classical or biblical history or mythology appropriate for the newly wed. The most flourishing cassone workshop in Florence was run by Marco del Buono Giamberti and Apollonio di Giovanni but major artists such as Domenico Veneziano and Botticelli may have decorated cassoni on occasion. Painted cassoni went out of fashion towards the end of the 15th century when carved oaken chests came into vogue. |

| Subjects depicted | |

| Place depicted | |

| Literary references |

|

| Summary | Apollonio di Giovanni (ca.1416-1465) was born in Florence where he trained as an illuminator in the circle of Bartolomeo di Fruosino (ca.1366-1441) and Battista di Biagio Sanguini (1393-1451). He became a member of the Arte dei Medici e degli Speziali in 1442 and of the Guild of St Luke in 1443. Marco del Buono (1402-1489) joined the Guild of St Luke in 1443. Together they run the most important workshop in fifteenth-century Florence from at least 1446. They produced decorated furniture panels (‘forzieri/cassoni’, wedding chests, ‘deschi da parto’, birth trays, ‘spalliere’, wainscotting) as well as illuminated manuscripts. This panel is a detached part of a Florentine marriage chest, known as ‘cassone’, i.e. a wedding chest, made in the occasion of a marriage between two members of important families, and belonged to the bridal trousseau. These pieces had often appropriate scenes painted on them such as the here depicted ‘Continence of Scipio’. The Roman general Scipio Africanus, after the defeat of Carthage was offered a beautiful woman called Lucretia as his captive. But when he was told of her betrothal to the Carthaginian Allucius, Scipio nobly returned Lucretia to him and returned the gold sent as ransom by her parents. Scipio is shown standing by the carpet which is covered with gold objects sent as ransom, and on the other side the marriage takes place. |

| Bibliographic references |

|

| Collection | |

| Accession number | 5804-1859 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 15, 1999 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest