Teapot

1852-60 (made)

| Artist/Maker | |

| Place of origin |

This teapot is made of Britannia metal, an alloy consisting primarily of tin that is similar to pewter, the most common household metal prior to the early 1800s. Britannia metal production developed however in response to the Sheffield plate industry and it borrowed much of the technology. The lobes on this teapot, like Sheffield plate, were stamped in a fly-press before the parts were assembled.

Britannia metal and modern pewter, containing antimony and no lead, are virtually indistinguishable. They are alloys that consist primarily of tin. Adding metals such as copper and antimony makes them harder and more durable.

By the 1850s, the use of Britannia metal superseded pewter for cheap mass-produced items. In the 1886 novel Patience Wins George Manville Fenn describes how the hero comes across a Britannia Metal factory: "As I looked through into these works, one man was busy with sheets of rolled-out Britannia metal, thrusting them beneath a stamping press, and at every clang with which this came down a piece of metal like a perfectly flat spoon was cut out and fell aside, while at a corresponding press another man was holding a sheet, and as close as possible out of this he was stamping out flat forks, which, like the spoons, were borne to other presses with dies, and as the flat spoon or fork was thrust in it received a tremendous blow, which shaped the bowl and curved the handle, while men at vices and benches finished them off with files. ...in spite of the metal being cold, the heat of the friction, the speed at which it goes, and the ductility of the metal make it behave as if it were so much clay or putty."

Britannia metal and modern pewter, containing antimony and no lead, are virtually indistinguishable. They are alloys that consist primarily of tin. Adding metals such as copper and antimony makes them harder and more durable.

By the 1850s, the use of Britannia metal superseded pewter for cheap mass-produced items. In the 1886 novel Patience Wins George Manville Fenn describes how the hero comes across a Britannia Metal factory: "As I looked through into these works, one man was busy with sheets of rolled-out Britannia metal, thrusting them beneath a stamping press, and at every clang with which this came down a piece of metal like a perfectly flat spoon was cut out and fell aside, while at a corresponding press another man was holding a sheet, and as close as possible out of this he was stamping out flat forks, which, like the spoons, were borne to other presses with dies, and as the flat spoon or fork was thrust in it received a tremendous blow, which shaped the bowl and curved the handle, while men at vices and benches finished them off with files. ...in spite of the metal being cold, the heat of the friction, the speed at which it goes, and the ductility of the metal make it behave as if it were so much clay or putty."

Object details

| Categories | |

| Object type | |

| Materials and techniques | Britannia metal, antler |

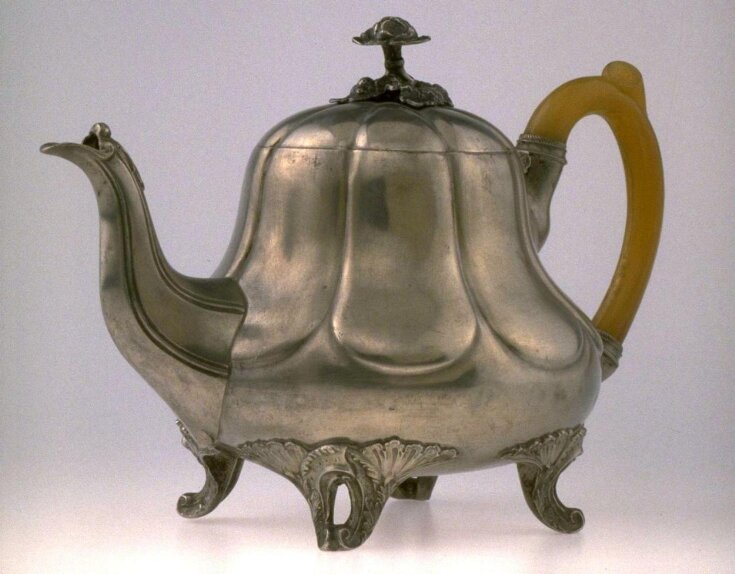

| Brief description | Britannia metal, the handle of carved antler horn, Sheffield, 1852-60, made by Buxton and Russell. |

| Physical description | Teapot with circular body made up of upwards-flowing, concave lobes, the four feet cast as leaves and the handle of the detachable lid cast as a flower. The spout is decorated with sweeping bands to match the lobes and the handle is of antler. |

| Dimensions |

|

| Marks and inscriptions | 4, BUXTON & RUSSELL'S, SHEFFIELD, EXTRA HARD, 972, C (Stamped on base) |

| Gallery label | Belinda Gentle Metalware Gallery (Room 116)

TEAPOT

Stamped Britannia metal, with cast elements and horn

Sheffield, England; 1852-60

Made by Buxton & Russell (partners 1852-60)

Stamped '4, BUXTON & RUSSELL'S, SHEFFIELD, EXTRA HARD, 972, C' on base

Britannia metal is often mistaken for pewter. Developed in response to the Sheffield plate industry, it borrowed much of the technology. The lobes on this teapot, like Sheffield plate, were stamped in a fly-press. By the 1850s, the use of Britannia metal superseded pewter for cheap mass-produced items. Britannia metal and modern pewter, containing antimony and no lead, are virtually indistinguishable.

Museum no. AP.734(November 2004) |

| Object history | The teapot was originally acquired by the Museum as an 'Animal Product' (hence the AP prefix to the museum number) because the handle is made of antler. |

| Historical context | This teapot is made of Britannia metal, an alloy consisting primarily of tin that is similar to pewter, the most common household metal prior to the early 1800s. Britannia metal production developed however in response to the Sheffield plate industry and it borrowed much of the technology. The lobes on this teapot, like Sheffield plate, were stamped in a fly-press before the parts were assembled. Britannia metal and modern pewter, containing antimony and no lead, are virtually indistinguishable. They are alloys that consist primarily of tin. Adding metals such as copper and antimony makes them harder and more durable. Buxton and Russell, the makers of the teapot are listed in White's 1857 directory of Derbyshire as "Buxton & Russell, mfrs. of extra hard Britannia metal and electro-plated goods, and spoon and fork mfrs., Duke pl., St. Mary’s rd. and Matilda st." By the 1850s, the use of Britannia metal superseded pewter for cheap mass-produced items. In the 1886 novel Patience Wins (Blackie & Son Ltd, London, Glasgow and Dublin, 1886) George Manville Fenn describes how the hero comes across a Britannia Metal factory: "As I looked through into these works, one man was busy with sheets of rolled-out Britannia metal, thrusting them beneath a stamping press, and at every clang with which this came down a piece of metal like a perfectly flat spoon was cut out and fell aside, while at a corresponding press another man was holding a sheet, and as close as possible out of this he was stamping out flat forks, which, like the spoons, were borne to other presses with dies, and as the flat spoon or fork was thrust in it received a tremendous blow, which shaped the bowl and curved the handle, while men at vices and benches finished them off with files. ... in spite of the metal being cold, the heat of the friction, the speed at which it goes, and the ductility of the metal make it behave as if it were so much clay or putty." Britannia metal's light robustness even came to the attention of Charles Dickens. 'Pleasantry, sir!' exclaimed Pott with a motion of the hand, indicative of a strong desire to hurl the Britannia metal teapot at the head of the visitor. 'Pleasantry, sir! - But - no, I will be calm; I will be calm, Sir;' in proof of his calmness, Mr. Pott flung himself into a chair, and foamed at the mouth. (The Pickwick Papers, Chapter 18) |

| Summary | This teapot is made of Britannia metal, an alloy consisting primarily of tin that is similar to pewter, the most common household metal prior to the early 1800s. Britannia metal production developed however in response to the Sheffield plate industry and it borrowed much of the technology. The lobes on this teapot, like Sheffield plate, were stamped in a fly-press before the parts were assembled. Britannia metal and modern pewter, containing antimony and no lead, are virtually indistinguishable. They are alloys that consist primarily of tin. Adding metals such as copper and antimony makes them harder and more durable. By the 1850s, the use of Britannia metal superseded pewter for cheap mass-produced items. In the 1886 novel Patience Wins George Manville Fenn describes how the hero comes across a Britannia Metal factory: "As I looked through into these works, one man was busy with sheets of rolled-out Britannia metal, thrusting them beneath a stamping press, and at every clang with which this came down a piece of metal like a perfectly flat spoon was cut out and fell aside, while at a corresponding press another man was holding a sheet, and as close as possible out of this he was stamping out flat forks, which, like the spoons, were borne to other presses with dies, and as the flat spoon or fork was thrust in it received a tremendous blow, which shaped the bowl and curved the handle, while men at vices and benches finished them off with files. ...in spite of the metal being cold, the heat of the friction, the speed at which it goes, and the ductility of the metal make it behave as if it were so much clay or putty." |

| Bibliographic reference | David Lamb, "Britannia Metal", The Journal of the Antique Metalware Society, Vol. 8, June 2000 |

| Collection | |

| Accession number | AP.734 |

About this object record

Explore the Collections contains over a million catalogue records, and over half a million images. It is a working database that includes information compiled over the life of the museum. Some of our records may contain offensive and discriminatory language, or reflect outdated ideas, practice and analysis. We are committed to addressing these issues, and to review and update our records accordingly.

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

You can write to us to suggest improvements to the record.

Suggest feedback

| Record created | December 15, 1999 |

| Record URL |

Download as: JSONIIIF Manifest